Column: How John Proctor and #MeToo helped cure my ‘work in progress’ theater phobia

- Share via

Some people get anxious when they fly, I get tense when I go to a play. Particularly if the space is small and intimate and there is no intermission.

I fret about tech disasters and dropped lines, bad casting and flawed sets as if I were the playwright’s mother or some make-or-break investor. Mostly, I worry that it will be terrible and that I will be trapped. Theater is an active, communal experience; what if I, as an audience member, can’t hold up my end because despite what the reviewers said, I just really hate this play? It’s not like I can hit the remote or get up and leave. I can’t even slump in my seat and commune in horrified hilarity with my friends. The people who are making it are right there.

And that’s for a play that’s finished. Watch a work in progress? Honey, there’s not enough Xanax in the world.

Then my older daughter became a summer intern at the 22nd Ojai Playwrights Conference’s New Works Festival and so I went to the final production. By the time it ended, with a denunciation of John Proctor, a celebration of Lorde and 200 people on their feet cheering, crying and dancing their way onto the stage, my theater anxiety had vanished; I was cured.

Within moments, it became impossible to distinguish between those involved in the dramatic reading of Kimberly Belflower’s “John Proctor Is the Villain,” the ninth and final work of the festival, and those who had just watched it.

And that is the point, or at least one of the points, of the Ojai Playwrights Conference — that in theater, the audience is part of the creative process and that can be a thing of joy, not judgment.

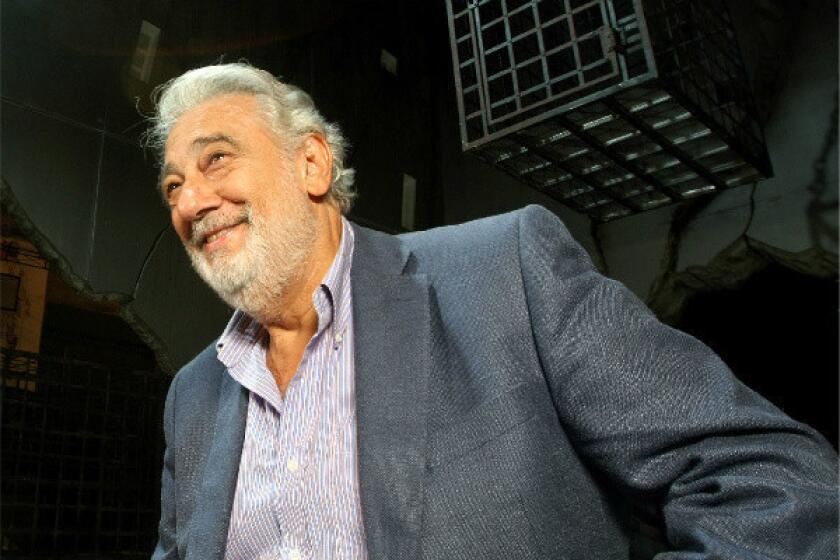

Because art is just one part of our conversation, often imperfect, occasionally amazing, with reality. Set in a tiny town in Georgia, where the high school lit teacher is also the sex ed teacher, “John Proctor Is the Villain” is a post-#MeToo tale, dealing with the same tradition of long exploitation and just-broken silence that has L.A. Opera scrambling to investigate sexual harassment allegations against Plácido Domingo.

Hence Lorde’s “Green Light” and all that cheering and crying.

Opera fans, performers and others sound off on Domingo’s statement about sexual harassment allegations, which seems to blend apology and excuse.

Though new to me, it was perhaps not unusual for longtime supporters of the festival. For more than 20 years, a small group of writers has gathered for two weeks in the hazy heat of the Ojai hills to work on plays that have been chosen by the Ojai conference’s artistic director, Robert Egan, and his staff. The first week is full of readings, rewrites and conversations, not all of them easy, that continue into the second as the plays are staged and then performed.

Belflower’s was not the only work that dealt with sexual harassment — in Kate Cortesi’s “Love,” a woman grapples with the difference between consensual and carefully coerced. Other plays at this year’s conference included a powerful vision of black rage (Dave Harris’ “Tambo & Bones”) and an exploration of Asian female stereotypes in Kimber Lee’s “untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play” as well as an intersectional event on climate change called “Wake Up: Imagining Our Future.”

“From the beginning, I said we are going to be unashamed big-P political,” says Egan, who has run the conference since 2002. “We celebrate writers who dare and care to write about the world we live in and the challenges we face as a community and a species. Women’s voices were very strong this year.”

“Every year, the plays pertain to what’s going on in the world,” says Judy Ovitz, longtime sponsor and Ojai resident, “but especially this year.”

Many critically acclaimed works have come through Ojai, including Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori’s “Fun Home,” Jon Robin Baitz’s “Other Desert Cities,” Stephen Adly Guirgis’ “The Mother... With the Hat” and Danai Gurira’s “Eclipsed.” Some playwrights arrive as well-known veterans, others right out of college programs; for some, says Egan, the former producing artistic director of the Mark Taper Forum, the conference marks the first time they have seen their plays performed.

Belflower falls more into the latter category. After getting an MFA from the University of Texas at Austin in 2017, she took a job with Meow Wolf, an experimental interactive art collective in Sante Fe, N.M. She had also applied for the Farm Theater’s College Collaboration, a commission granted by three colleges each year to a young playwright who then works with students to develop a play.

She originally pitched a whole other project, but she was preparing for the first interview with the Farm team when the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke and it soon became clear to her “that I could not write about anything else.”

She just wasn’t sure how, though she did have a notion about re-examining “The Crucible” from a more modern point of view — how exactly was Proctor considered a hero when he upheld a society in which women, including his wife, had no power and he then seduced a 16-year old orphan in his employ?

She even had a title — “John Proctor Is a Villain” — that impressed the Farm’s artistic director, Padraic Lillis, as much as Belflower’s original project, and she got the commission. While she worked at Meow Wolf, Belflower began interviewing a variety of students at three Southern colleges.

“I asked them about their experiences with sex ed, and everyone had something to say about that,” Belflower says. “I also asked them about anger — what do they do when they’re angry, how does it make their bodies feel, what can’t they do when they’re angry — and things like how they would feel if one of their favorite actors had been accused of something.”

Each school then put on a production of “John Proctor” and Belflower eventually did a reading in Los Angeles, after which her friend Hannah Wolf and her dramaturg, Tiffany Moon, who is also the artistic associate at the Ojai Conference, urged her to submit to OPC.

“I still can’t believe I was in the same conference as some of those plays and playwrights,” she says. Each play is first given a table read by actors for an audience of the other playwrights, conference staff and a few community and board members. Hers was the last read during the first week, which was “intimidating,” she says. “But having seen how the process worked, I knew the feedback would be sharp and insightful.”

Over the following days, she cut 20 pages, strengthened certain character arcs, added an explanation of “The Crucible” for those who might not be familiar with it and made innumerable small changes in preparation for Sunday night’s performance.

“She did a lot of work,” Egan says, adding that he chose “John Proctor” as the final play performed because its message of women finding their voice, and its animated ending, seemed a perfect way to close the conference.

“There’s a release at the end, which was just the right note,” he says.

Days later, Belflower is still stunned by the audience, well, not just its reaction to but also its involvement in “John Proctor.”

Before all the cheering, crying and dancing at the end, there had been gasps of recognition, angry murmurs, startled laughter and tense silence as a group of students moved through their own moments of denial and revelation, accusation, rejection and reclamation. My 12-year-old daughter was just as engaged as audience members at least half a century older than she was. Yes, this is a group with a vested interest in theater, but for two hours, it felt like something was happening, not being performed.

That it resonated so powerfully with so many generations thrilled Belflower and also pained her. “I drew a lot on my own experience, and it was depressing to see how that experience is still being shared by kids today, and how little it had changed from that of older people.”

She’s not sure what will happen next — she’s still looking for an agent — but I can’t wait to see where “John Proctor,” or any of this year’s plays, goes from here. I wish I had seen them all.

Fortunately, there’s always next year.

Geraldine Inoa’s “Scraps” and Dionna M. Daniel’s “Gunshot Medley” explore pain in the fight for control over black bodies in America and demonstrate exciting new directions in African American stage works

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.