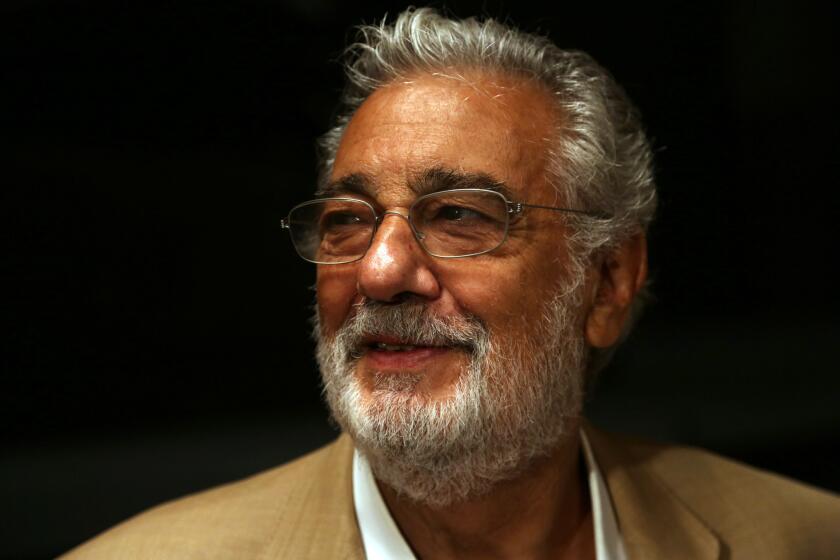

Why Plácido Domingo’s response to sexual harassment allegations is drawing heavy fire

- Share via

When news spread Tuesday that Plácido Domingo had been accused by nine women of sexual harassment over three decades, reactions from the opera world included sadness and anger that were only amplified by Domingo’s response to the allegations.

After the Associated Press detailed alleged instances of unwanted sexual advances and perceived retaliation when those advances were rejected, the general director of Los Angeles Opera and arguably the most famous living figure in classical music responded by calling the report “inaccurate” and by offering a blend of apology and excuse, seeming to imply that any alleged offending behavior in years past needed to be judged by more lenient standards.

Domingo’s statement to the AP:

“The allegations from these unnamed individuals dating back as many as 30 years are deeply troubling, and as presented, inaccurate.

“Still, it is painful to hear that I may have upset anyone or made them feel uncomfortable — no matter how long ago and despite my best intentions. I believed that all of my interactions and relationships were always welcomed and consensual. People who know me or who have worked with me know that I am not someone who would intentionally harm, offend, or embarrass anyone.

“However, I recognize that the rules and standards by which we are — and should be — measured against today are very different than they were in the past. I am blessed and privileged to have had a more than 50-year career in opera and will hold myself to the highest standards.”

That statement landed with a thud to many opera fans and professionals on Tuesday.

Ian Barnard, 59, an English professor at Chapman University who lives in downtown L.A., said he has been an L.A. Opera subscriber for more than 10 years. He thought Domingo’s statement sounded like “a pathetic attempt at damage control. He says, ‘Well, you realize things change, we have a different climate now.’ We’re talking about sexual harassment. Even 30 years ago, sexual harassment was not OK.”

Barnard said he also was alarmed by the AP report’s contention that the company protected Domingo and that harassment was tolerated. “L.A. Opera and their board of directors I’m sure wanted to keep this big superstar who was bringing in crowds and turn a blind eye to what they’d heard and what they must’ve known was going on,” he said.

Matthew Martinez, 38, an IT manager and choral conductor who lives in Costa Mesa, was troubled by what he saw as a contradiction in Domingo’s statement.

“He’s admitting that the ‘rules and standards’ have changed but declares that his relationships were always welcomed,” Martinez said. “If that’s true, then why does it matter that rules and standards have changed? He’s trying to have it both ways.”

What would Martinez have preferred to hear? A simple “I’m sorry.”

“Domingo’s inability to look inward with his words only makes things worse for his victims and makes him look guilty,” Martinez said.

Accusations of harassment against Plácido Domingo dating back to the 1980s raise many questions, and generate a statement of denial from the opera legend.

Samuel Schultz, a 32-year-old opera singer in New York City, saw Domingo’s response as part of the broader industry’s “archaic” response to accusations of misconduct.

Schultz has accused noted countertenor David Daniels and Daniels’ husband, William “Scott” Walters, of drugging and raping him in 2010. Daniels and Walters, who deny the allegations, were indicted last month in Texas on sexual assault charges.

Domingo’s statement “places the blame on generation and age,” Schultz said. “It refers to the women in dehumanizing ways, calling them ‘unnamed,’ which is false, because one of the women is named in the article.”

By keeping Domingo in place as L.A. Opera general director while an investigation gets underway, the company is sending the wrong message, Schultz said. “I think the institution owes not only its young artists but the entire opera community and the public community in Los Angeles a much better response.”

Aliana de la Guardia, 36, co-artistic director of Guerilla Opera in Boston, said Domingo probably believes what he said.

“He probably does not think that his advances were unwanted,” she said. “I think a lot of this predatory behavior is probably not perceived to the predators as being that way.

“I think that to him, in his head, he was just a big star and everyone wanted him. And to the rest of us he was just, you know, this creepy guy that could make or break your career.”

De la Guardia is one of four former Boston Conservatory students who accused an influential music professor of sexual misconduct and abuse in 2017. She said she understood the scenarios outlined in the AP report.

“I’ve been propositioned. I’ve been offered a job, and it’s been taken away when I didn’t accept the proposition,” she said. “To some degree, I get why he thought he could do that, although it was not right for him to do.”

Domingo is the latest in a series of classical music #MeToo cases. In 2018, the Metropolitan Opera in New York fired conductor James Levine after an investigation found credible evidence of “sexually abusive and harassing conduct.” Also in 2018, Charles Dutoit stepped down from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London following workplace sexual assault allegations by multiple women. Prominent professors and some singers also have lost jobs after allegations of abuse and harassment were found to be credible.

Placido Domingo took a so-called Joe Biden defense after allegations of sexual harassment by nine women. A look at the cultural shifts to help understand what might happen next.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.