‘Minions’ is inescapable. So is the blockbuster’s musical mastermind, Jack Antonoff

- Share via

For a guy who got his first big break with a song called “We Are Young,” Jack Antonoff sure seems fixated on old music.

At last month’s Bonnaroo festival in Tennessee, Antonoff — former guitarist of the pop-rock trio fun., whose exultant (if somewhat cringe) 2012 smash about youth topped Billboard’s Hot 100 for six weeks on its way to winning song of the year at the Grammy Awards — convened a bunch of musician pals for an all-star tribute to his birth year of 1984.

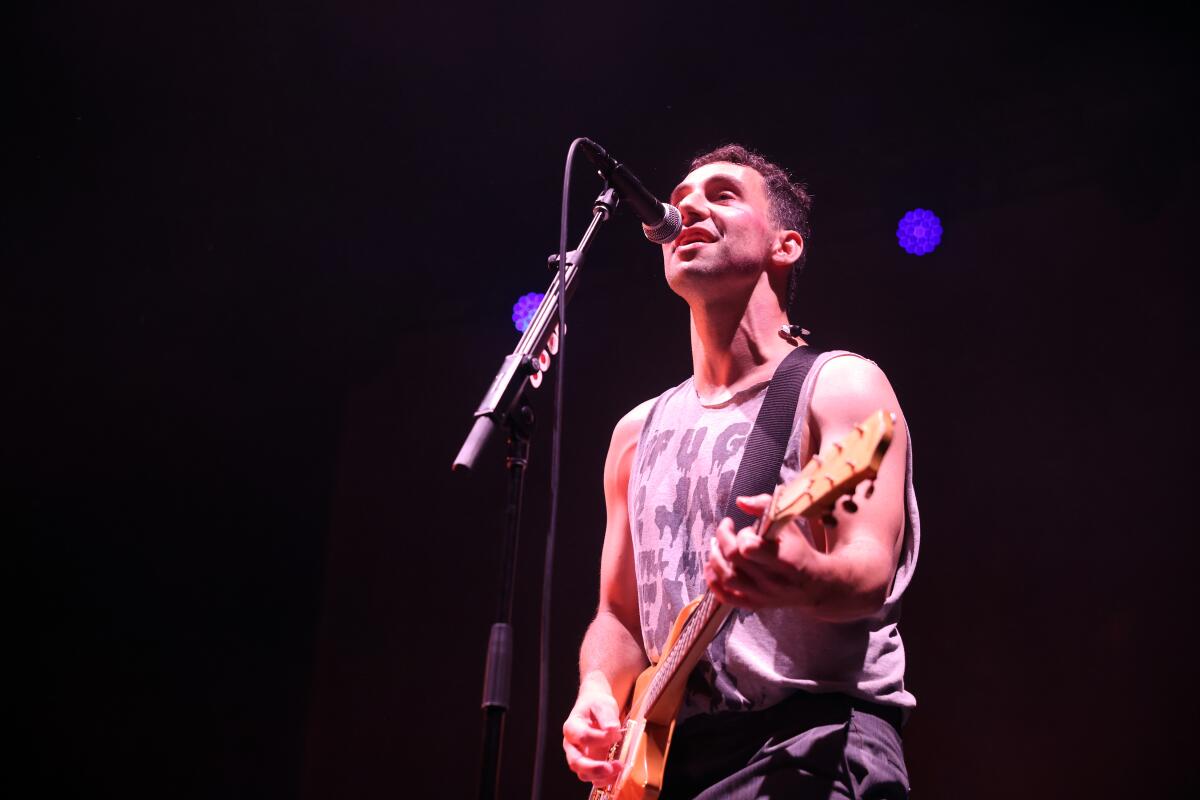

Last week, he played Inglewood’s Kia Forum with his current group, Bleachers, which stopped channeling Bruce Springsteen’s time-honored thoughts on girls and New Jersey only to cover Tom Waits’ “Jersey Girl.”

A few days after that show, the latest “Minions” movie landed in theaters with an Antonoff-assembled soundtrack of indelible ’70s hits newly recorded by the likes of Thundercat, Kali Uchis, St. Vincent, H.E.R. and Caroline Polachek. “The Rise of Gru,” as the animated film is called, set a Fourth of July box office record, which almost certainly means that millions more grade-schoolers have now heard “Fly Like an Eagle” than had the weekend before.

It’s no wonder Antonoff, 38, keeps rifling through the used bins: Old music is big business these days, with so-called catalog material accounting for 70% of what was streamed last year on services such as Spotify and Apple Music, according to MRC Data. Thanks in large part to TikTok, vintage tunes like Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” and Matthew Wilder’s “Break My Stride” have surged onto streaming charts; Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God)” sits at No. 6 on the Hot 100, ahead of Beyoncé’s new single, after it was prominently featured in Netflix’s “Stranger Things.”

Bush, a rare female auteur in the male-dominated music world, has inspired a raft of acclaimed artists from Fiona Apple to FKA Twigs to Japanese Breakfast.

Indeed, “The Rise of Gru” isn’t this summer’s only Hollywood blockbuster with a soundtrack of familiar melodies. For his splashy take on the life of Elvis Presley, Baz Luhrmann recruited Doja Cat, Eminem, Kacey Musgraves and Stevie Nicks, among others, to punch up Presley’s music, while “Top Gun: Maverick” recycles Kenny Loggins’ “Danger Zone” to accompany a nearly shot-for-shot re-creation of the original “Top Gun’s” opening sequence.

Yet Antonoff’s retro leanings have actually made him a major player shaping the sound of modern pop. More than Bleachers — a moderately successful alt-rock radio act headlining an arena for the first time at the Forum — what he’s best known for is his production and songwriting for and with superstars including Taylor Swift and Lorde and acclaimed critics’ faves such as Lana Del Rey, Clairo and St. Vincent. When the Chicks got back together a couple of years ago (minus the “Dixie”), the groundbreaking country trio hired Antonoff to oversee their return; when Olivia Rodrigo revised the credits for her album “Sour” to acknowledge some crucial inspirations (and perhaps to stave off a copyright lawsuit or two), Antonoff’s name was among those added. At April’s Grammys ceremony he was named producer of the year — one of four Grammys he’s won, along with fun.’s two, for his behind-the-scenes studio work.

Antonoff’s touch — his ability to blend classic and cutting-edge, cult and mass, intimate and anthemic — has proven sufficiently zeitgeist-y that he’s started attracting older musicians eager to connect with fans of the millennial and Gen Z artists who idolize them: Diana Ross and Earth, Wind & Fire’s Verdine White both appear on the “Rise of Gru” soundtrack, while Springsteen himself puts in a cameo on Bleachers’ third LP, 2021’s “Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night,” which got no higher than No. 27 on the Billboard 200 but which scored Bleachers a last-minute booking on “Saturday Night Live” in January after Roddy Ricch bailed due to a COVID exposure.

So what is it precisely that Antonoff does? In interviews, he routinely describes his production approach as an act of emotional availability — establishing a secure environment for artists to express themselves, then responding in a way that encourages them to keep going further than they otherwise might. Whatever arrangement he helps devise depends entirely, in his telling, on where the artist has led him. “Production isn’t someone with the coolest snare sound,” he told The Times in 2019. “Production is the idea.”

It’s a willful throwback to a more collaborative, exploratory age before hitmakers like Max Martin and the Neptunes provided pop stars and rappers with nearly finished tracks awaiting a marquee vocal performance; it’s also, in the wake of sexual-abuse allegations against the once-powerful Dr. Luke, a shrewd assurance of his respect for women in the workplace. (Jack Antonoff: the original gentleminion.) So inescapable did he seem last year that a mild backlash began forming among listeners who felt he’d overplayed his hand as a female ally — at least until he turned up yet again as Florence Welch’s right-hand man on Florence + the Machine’s well-received “Dance Fever.”

Still, that framing downplays Antonoff’s reliance on a variety of sonic hallmarks: booming drums, airy synths, snaking guitar lines, reverb-drenched vocals, each rooted in a lifetime of obsessive listening and tinkering with both instruments and software. That you can detect his fingerprints throughout the songs from “Minions” — even in cuts as distinct as Phoebe Bridgers’ winsome take on the Carpenters’ “Goodbye to Love” and Brockhampton’s swaggering run through “Hollywood Swinging” by Kool & the Gang — is an indication of how finely he’s honed his textural palette. Maybe too finely: For Bleachers’ rendition of John Lennon’s “Instant Karma!” Antonoff made the insane choice to forgo the late Alan White’s iconic drum fill.

Antonoff, an occasional tabloid presence thanks to his relationships with actresses Lena Dunham and Margaret Qualley, isn’t alone in his flair for slightly denaturing sounds familiar to any music fan. Smart, young-ish acts curious about the history of pop and rock — your Haims and Vampire Weekends and Lady Gagas — have sought out other writer-producers such as Ariel Rechtshaid, Rostam, Blake Mills and Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker, the last of whom teamed with Ross and Antonoff for a standout original, “Turn Up the Sunshine,” for “The Rise of Gru.”

Taken together, these guys’ efforts reflect an era in which the creative instinct has grown inseparable from the curatorial one — when the only way to say something honest about your life is to acknowledge that each of your experiences was shaped by those who experienced and then sang about them before you did.

“I miss Long Beach and I miss you, babe / I miss dancing with you the most of all,” Del Rey purrs in “The Greatest,” a stately piano ballad she and Antonoff co-wrote for 2019’s richly allusive (and endlessly memeable) “Norman F— Rockwell!” “I miss the bar where the Beach Boys would go / Dennis’ last stop before ‘Kokomo.’”

What does distinguish Antonoff, who came up playing in punk bands in his native New Jersey before breaking out with fun., is his eagerness to forget that he knows all that. Fronting Bleachers at the Forum, he began the show in proudly nerdy media-studies mode, mumbling the band’s “91,” about watching the Gulf War on TV, in front of a flickering box; within 15 minutes or so, he pretended to decide that the sweater he’d worn onstage had been a bad move.

“No f— way I’m playing this song in a cardigan,” he said as he tore it off (along with his Coke-bottle eyeglasses) to reveal a sleeveless T-shirt, his bandmates revving up the monstrous and chiming “How Dare You Want More” behind him. And that was where Antonoff, perhaps the unlikeliest rock star since Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo, achieved something like an escape into the fantasy his music holds out. It’s not that the songs about grief and ambition were mapping new thematic territory; it’s definitely not that the “Born to Run” glockenspiel licks were doing something you’d never heard.

But the emotional energy felt incredibly pure as he and the rest of Bleachers pushed their way to a sweet spot where you couldn’t tell the difference between a blaring guitar and a blaring saxophone. He wasn’t lost in the music, exactly, but he didn’t seem to want to find his way back.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.