It’s 2022. Does Elvis Presley still matter?

- Share via

Thanks to Baz Luhrmann’s lavish new biopic, Elvis Presley is about to have a moment.

He needs one.

The second half of the 20th century, for those who came of age during it, was in essence one giant Elvis moment. He was at the epicenter of pop culture from the opening “well” of his first No. 1 hit, “Heartbreak Hotel,” in 1956, through his death in 1977 and beyond.

John Lennon said, “Without Elvis, there would be no Beatles,” encapsulating the seismic effect Presley had upon popular music. He had 18 No. 1 hits, including such standards of the rock ’n’ roll era as “Jailhouse Rock,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” “Hound Dog,” “It’s Now or Never” and “Suspicious Minds.”

His earliest records for Sun captured a kinetic blend of country, blues and pop, a hybrid that would become known as rockabilly, while his later years as a Vegas showman established a path toward maturation for generations of pop stars to come.

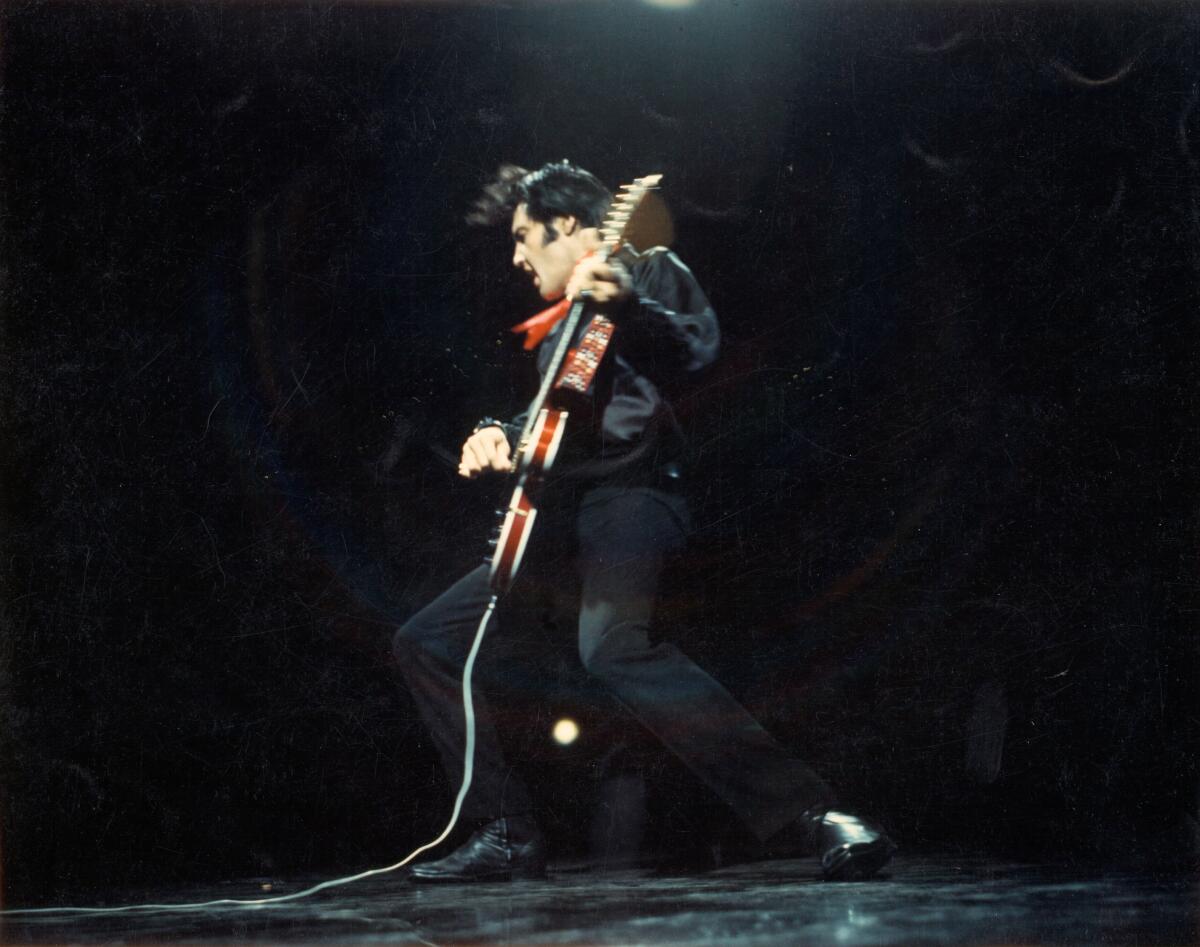

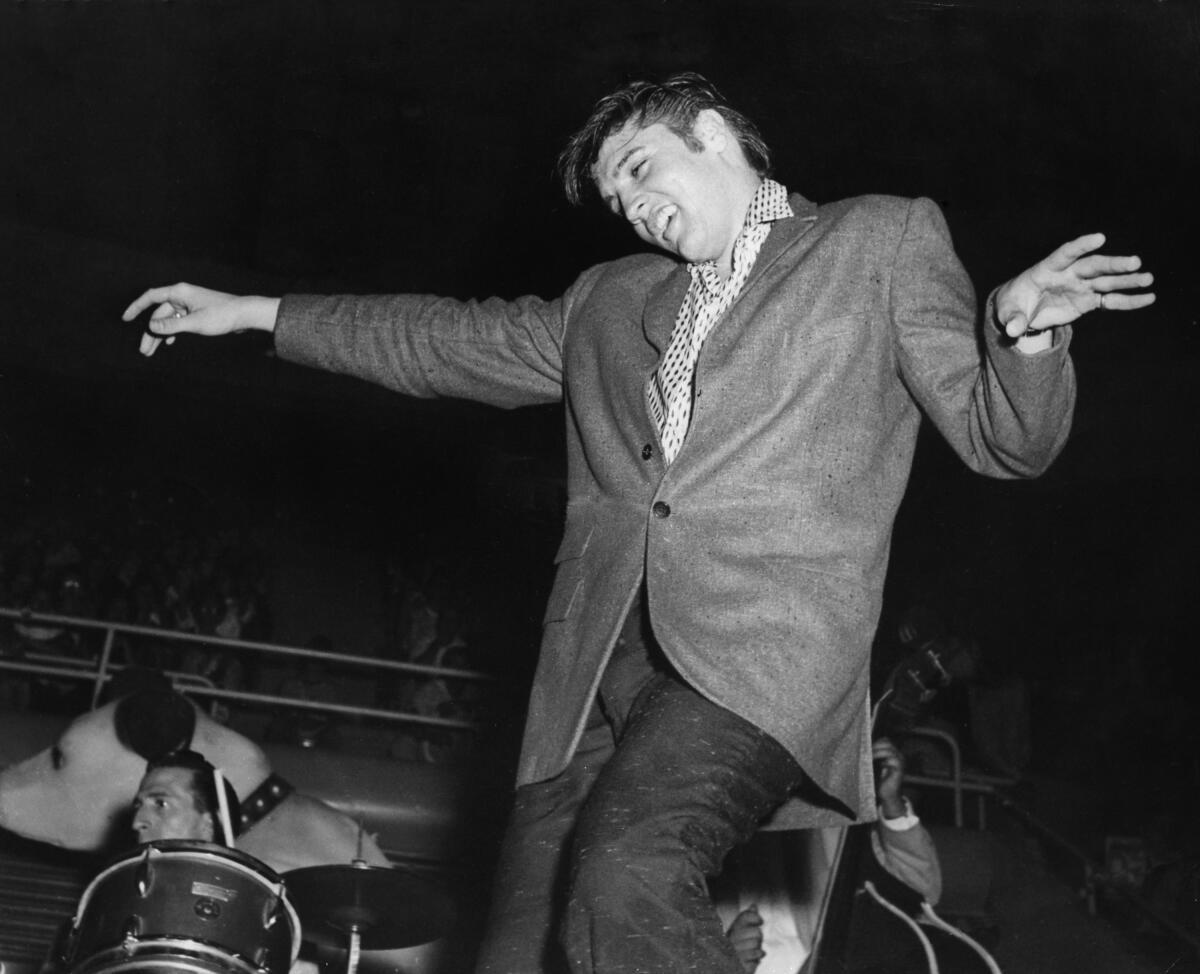

Presley’s hold on the popular consciousness extended beyond mere records, into generational and sexual politics, the lure of Hollywood and the dark side of the American dream. Blessed with preternatural good looks, Elvis exuded such a palpable carnal charisma that his 1956 appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” caused a sensation because of his sexy gyrations; famously, the CBS censors insisted that the singer be shot from the waist up.

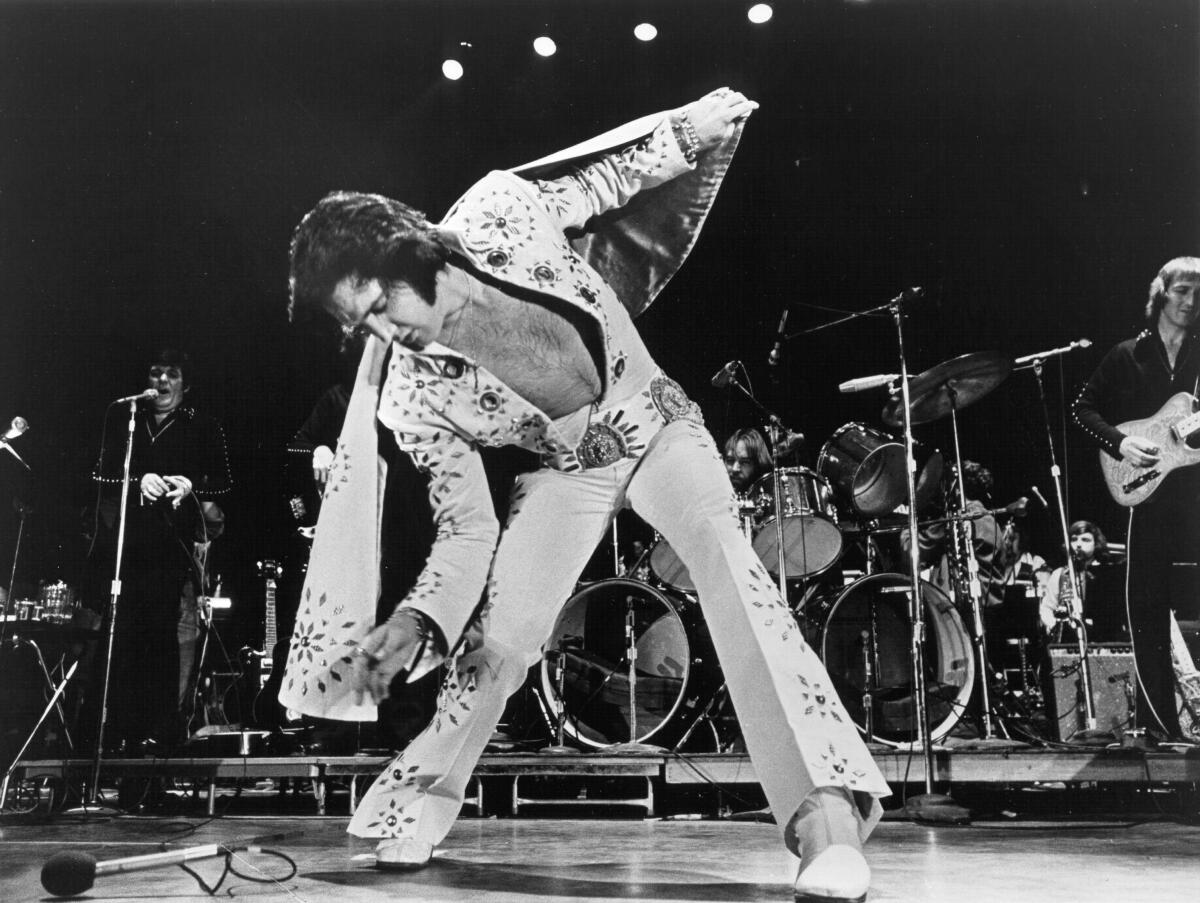

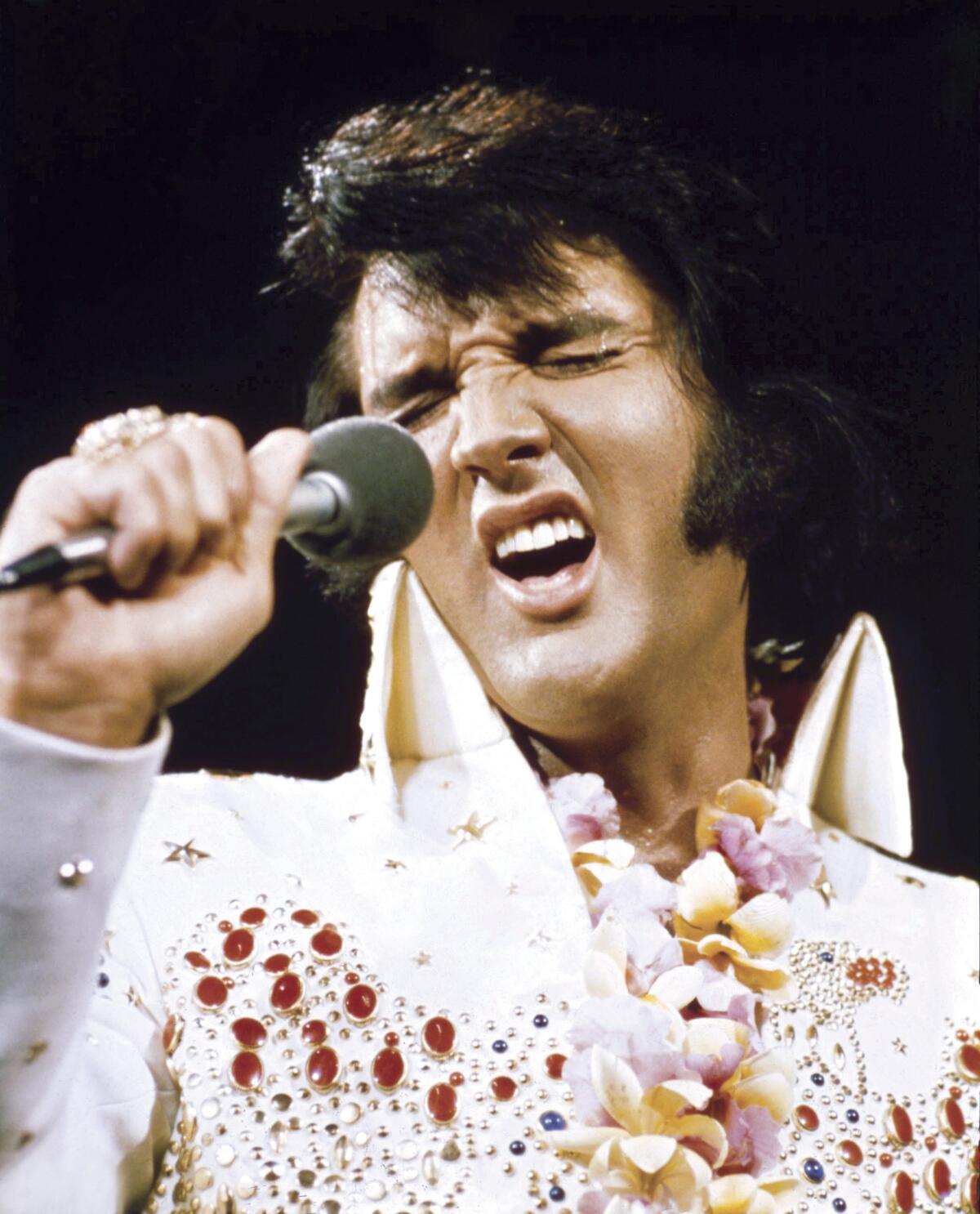

The image of the young, rebellious, lascivious rockabilly cat would eventually give way to its “after picture”: the bloated ’70s crooner. That persona — spangly jumpsuits that accentuated his increasing heft, mutton chops, karate kicks — became the pervasive one in pop culture, thanks to legions of Elvis imitators and scores of myths about Presley’s excessive appetites, stories that worked their way into movies and song.

That era seems quite distant from the vantage of 2022. It’s been 20 years since the compilation “ELV1S: 30 #1 Hits” topped the Billboard charts, aided by the JXL remix of “A Little Less Conversation.” It’s also been 20 years since Eminem cracked that kids were “embarrassed their parents still listen to Elvis,” which itself seemed a little outdated at the time. Michael Stipe’s Elvis impression on R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon,” a tribute to comedian Andy Kaufman’s Presley parody, may have been the last time Presley registered as cool. That was 1992.

“To be honest, no one I know under 30 cares or knows much about Elvis,” says Puja Patel, editor in chief of the tastemaking music site Pitchfork. “The classic version of rock ’n’ roll just doesn’t exist the way it once did, and that’s in large part because younger audiences are less interested in it.”

Enter the biopic. Over the last few years alone, “Bohemian Rhapsody” thrust Queen back into the spotlight and won Rami Malek an Oscar for his portrayal of its lead singer, Freddie Mercury. “Rocketman” helped cement the legend of Elton John, Jennifer Hudson brought Aretha Franklin’s story to life in “Respect,” while Danny Boyle’s recent Hulu series “Pistol” tells the tale of the Sex Pistols through the eyes of its guitarist, Steve Jones.

But is Elvis too old — not to mention too white and too male — for resurrection in 2022? His last Top 10 hit, “Burning Love,” arrived half a century ago, and his peak — and that of his pioneering ’50s rock ’n’ roll peers — is even further in the past.

Sean Ross, editor of the “Ross on Radio” newsletter and an observer of radio trends, notes: “Oldies radio stations pushed away from the 1950s close to 20 years ago. When the center of the format became the ’70s, the Elvis music you heard became a few post-comeback titles: ‘Suspicious Minds,’ ‘Burning Love,’ ‘In the Ghetto.’”

Ross adds that the term “oldies” itself is antiquated within the radio industry. Instead, this format is called “classic hits” and is “mostly focused on the ’80s and is starting to push into the ’90s and beyond. At this point,” says Ross, “classic hits stations have been living without Elvis since at least the mid-’10s.”

Presley performs respectably on streaming services, according to statistics from Luminate Entertainment Data, the organization that provides data for the Billboard charts. Luminate tracked a total of 13,791 radio spins of Presley’s music during the first quarter of 2008; this year, there were only 5,896. Over the last two years, Presley ranked in the mid-200s for overall streams. Save for Frank Sinatra, he’s the oldest artist on these charts, a testament to his enduring popularity among older generations but also a suggestion that the early rock ’n’ roll era is fading from the collective consciousness, existing in some kind of hazy netherworld between Ken Burns reveries of pre-modern times and the Beatles’ “Get Back” doc.

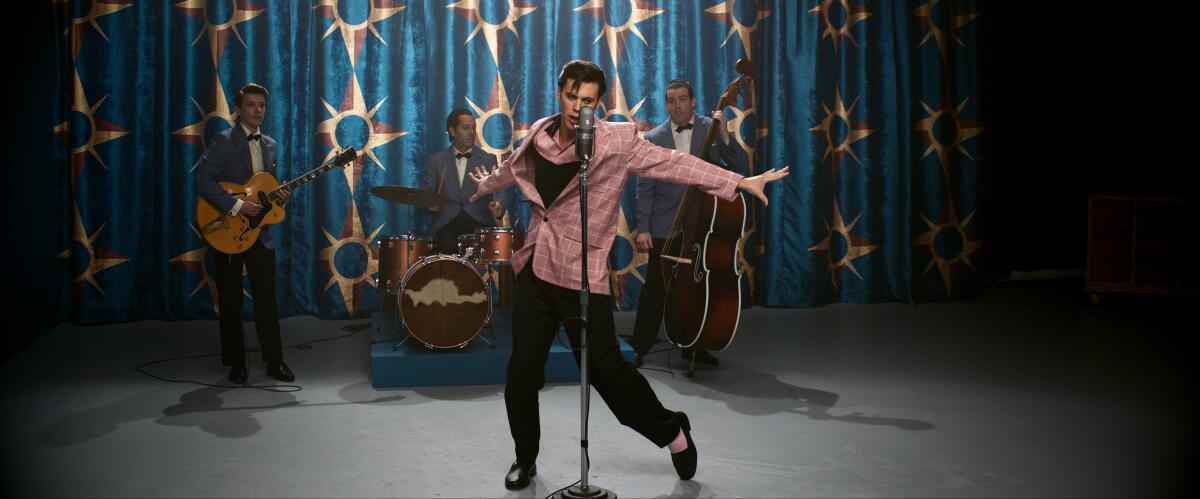

Luhrmann’s new “Elvis” movie is an audacious attempt to reframe Presley. The film, starring Austin Butler as the King and Tom Hanks as Col. Tom Parker, is designed not with historical accuracy in mind. Rather, it presents an idea of Elvis Presley, emphasizing how he shook up society by ignoring racial boundaries and sexual conventions, accentuating this rebellion not by relying on rock ’n’ roll — the wild, unkempt music that Presley made — but hip-hop and pop.

The soundtrack for “Elvis” is rife with interpolations that use Presley’s original recordings as a mere suggestion for the finished track: The Sun single “That’s All Right” is the basis for a collaboration between Diplo and rapper Swae Lee; Doja Cat’s “Vegas” is constructed on a loop from Big Mama Thornton’s original “Hound Dog”; and “The King and I” finds Eminem riffing on “Blue Suede Shoes” as Dr. Dre cuts up the main riff from “Jailhouse Rock.” When the soundtrack does showcase original, unremixed Elvis music, it’s from the over-the-top Vegas years, not the early days.

Austin Butler plays the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll and Tom Hanks plays his ruthless manager in the Cannes-premiered biopic.

For Elvis Presley Enterprises and Authentic Brands Group, the two organizations responsible for managing the Presley estate and likeness, it’s crucial that they keep their business alive by bringing in new fans.

“Elvis” can be seen as the culmination of a process that the two companies set in place roughly a decade ago. Back then, CKX — a company whose biggest asset was “American Idol” — offloaded the estate to a private equity firm, believing it to be in a state of decline. ABG purchased the rights for $145 million, entering a deal with EPE where all proceedings involving the Presley name and likeness would flow through Authentic Brand Groups, while Joel Weinshanker would serve as managing partner of Elvis Presley Enterprises, the company responsible for Graceland, the former home of Elvis in Memphis, Tenn., and other live events.

Weinshanker, 55, played a key role behind the scenes on “Elvis,” bringing Luhrmann and Butler for their first respective visits to Graceland. A former rock manager — he counted the hair metal band Trixter as a client — Weinshanker takes pride that he’s adopted “What Would Elvis Do?” as his operational credo.

Determining the answer to WWED involves research and received knowledge, not to mention conversations with former colleagues and friends of Elvis, including Weinshanker’s partner, Lisa Marie Presley, the lone daughter of Elvis.

Over the last few years, Weinshanker has classed up Graceland, establishing a luxury hotel called the Guest House on the property alongside new museums and a live performance space, plus the SiriusXM booth that pumps out the Elvis Channel to subscribers of the satellite service.

Who comes to visit this renovated Graceland? Weinshanker maintains that “there are 50,000 to 100,000 twentysomething women who come to Graceland every year,” along with couples and their babies. Derrill Argo, one of three DJs on SiriusXM’s Elvis channel, concurs that this is a family affair: “We will often meet three generations of people who were Elvis fans.”

It’s enough activity for Weinshanker to state, “The largest revenue year in Elvis Presley Enterprises history is 2022,” a figure that’s still in flux as much of the year is yet to come and, with it, not just the “Elvis” movie but also Elvis Week at Graceland.

Nowadays, most of the old guard arrives in August to celebrate Elvis Week, an annual event that grew out of the regular candlelight vigil held by mourning fans in 1978. For decades after Presley’s ignominious 1977 death — fates couldn’t conspire to deliver a less glamorous passing than dying on the toilet from a heart attack due to his addiction to pain pills — his legacy was kept alive through a steady stream of posthumous compilations, several of which were certified platinum over the years. But his presence was hardly limited to operations controlled by his estate or his longtime label, RCA, which is now owned by Sony.

Elvis impersonators were legion, so numerous that they became central figures in such films as 1992’s “Honeymoon in Vegas.” Rumors that he faked his own death ran rampant, culminating in tabloid stories suggesting that he had been spotted at a Burger King in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Elvis Costello swiped the first half of his stage name from the King, while Bruce Springsteen and John Hiatt wrote songs where Presley’s antics — shooting out televisions and giving Cadillacs away to his friends, respectively — served as punchlines.

Such tawdry sideshows are not part of the story told by either Elvis Presley Enterprises or “Elvis.” Weinshanker is counting on the film to bring in new, younger audiences unfamiliar with Presley’s legacy.

Describing “Elvis,” he says, “This is a frenetic, thousand-miles-an hour, by-the-seat-of-your-pants way of storytelling that I think resonates and connects most with teens.”

Weinshanker argues that Lurhmann zeroes in on the cross-cultural innovations that made Presley a sensation. “You also have to remember that the new internet generation can care less about appropriation,” he says. “Today, everyone appropriates everything.”

Appropriation is a subject that’s not treated so cavalierly among academics and activists, as it suggests inappropriate, even malicious, intent from a dominant culture cherry-picking items from people of color. Presley has been the subject of these accusations before, as his 1950s records borrowed heavily from blues and R&B figures, ultimately overshadowing such Black originators as Big Mama Thornton and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup.

One of the tipping points in Presley’s diminished reputation arrived in 1989 with Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” when Chuck D rapped, “Elvis was a hero to most but he never meant s— to me / Straight-up racist that sucker was simple and plain.”

Chuck D later clarified his lyric: “I never personally had something against Elvis. But the American way of putting him up as the King and the great icon is disturbing. You can’t ignore Black history. Now they’ve trained people to ignore all other history — they come over with this homogenized crap. So Elvis was just the fall guy in my lyrics for all that.”

Amanda Marie Martinez, a historian at Emory University, notes that recent academic studies concerning early rock ’n’ roll have been “trying to emphasize more racially inclusive but also gender-inclusive histories,” an idea that inevitably pushes Presley away from the focal point of rock history.

Often, historians writing about Presley presented him as a triumphant figure, the artist who helped introduce blues and R&B to a wider audience, suggesting that such an evolution might not have happened if it weren’t for Elvis, when the truth is more nuanced: Presley tapped into the musical cultural currents of the 1950s and 1960s, tying them together in unexpected, exciting ways.

Luhrmann’s “Elvis” attempts to convey that sense of excitement not through the use of original Presley music but by playing with his image, both as a rebellious youth and a melancholy middle-age crooner.

Many of the distasteful aspects of Presley’s life, such as falling in love with his future wife, Priscilla, when she was just 14 and he was 24, are treated gingerly or completely overlooked. “Elvis” argues that Presley is an icon of personal and public defiance, an outsider who forged his own path. Such a notion has long been at the core of teenage culture, but modern teens aren’t necessarily rebels without a cause. Far from rejecting their parents’ music, the youth of the 2020s embrace it.

Martinez points out, “There are other white males that continue to reverberate with people. Young people are still listening to the Beatles or David Bowie or Johnny Cash.”

Online culture is filled with examples of new audiences embracing old music, whether it’s Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” crashing back into cultural consciousness after it was used in a viral TikTok clip or Kate Bush’s “Running up That Hill” suddenly becoming a smash hit after being featured in the current season of “Stranger Things.” What ties together all this old music is that it comes from the era of album rock and MTV, highly produced and polished music that still sounds modern.

Presley’s music does not sound modern: It’s an artifact from a different America, one that is fading in popular consciousness. His earliest rockabilly sides sound raw and nervy, almost primitive in their simplicity, a wildness that’s a foreign concept in modern music.

Chris Isaak, a singer who has kept the fire of early rock ’n’ roll alive throughout his career and who appears on the “Elvis” soundtrack as well as providing the vocals for country star Hank Snow in the movie, has seen how Presley’s peers are being forgotten.

“I was talking to a young girl, and she’s a successful singer, so she knows music,” Isaak recounted. “I said, ‘Are you putting harmonies like the Everly Brothers on this?’ And there was a blank look in her eye. I said, ‘Are you acquainted with the Everly Brothers?’ She had no clue. That was kind of shocking to me. I think a new generation will see this movie and go, ‘Wow. I love this music. Who is this guy?’”

Maybe it’s inevitable that Elvis Presley would fade as rock ’n’ roll recedes into the history books. Elvis left the building a long time ago. Earlier this month, Graceland celebrated its 40th anniversary of being open to the public.

In three more years, Graceland will have been open to the public longer than Elvis Presley was alive. Luhrmann’s movie might goose ticket sales to Graceland, and perhaps Presley will rack up healthy numbers on Spotify, but these may wind up as temporary corrections to the permanent problem of the decline of rock ’n’ roll. Once the sound of youthful rebellion, rock ’n’ roll is now part of history, which means Elvis resides in the past, not the present.

“Without reintroduction, we forget who Julius Caesar is,” says Isaak. “Doesn’t matter how great you were in your moment, you will be forgotten. All things fade.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.