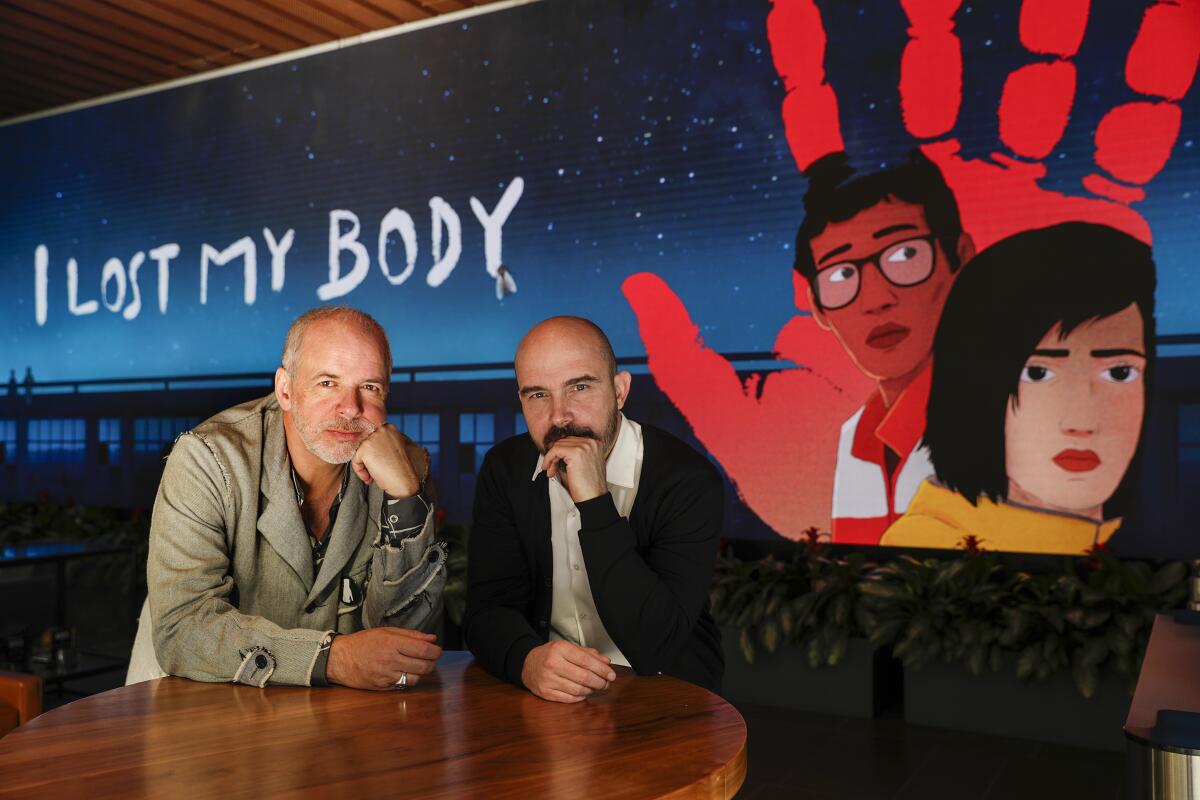

How Netflix’s ‘I Lost My Body’ turns animation on its head, with the story of a severed hand

An intrepid severed hand braves the streets of Paris in Jérémy Clapin’s Oscar-nominated “I Lost My Body,” an audaciously exceptional and critically adored animated feature. Separated in an accident from Naoufel (Hakim Faris), a downhearted young Moroccan immigrant, the sentient extremity carries with it tactile memories of childhood and traverses daunting obstacles to reach its destination. It’s certain that its return is critical to the survival of its owner.

Naoufel, who once aspired to being an astronaut or a pianist, has settled into the thankless monotony of a pizza delivery job and isolating loneliness. Already broken internally before getting physically injured, he must make peace with his incompleteness. Meanwhile, the yearning hand races back to him.

“We are not singular inside us, we are made by different parts of ourselves: childhood, hopes, dreams, regrets,” Clapin said recently during a stop in Los Angeles for the chaos of awards season. “Sometimes life, destiny, removes things from us, and when the hand gets detached from the body, it’s like childhood gets detached from it too.”

Independently produced at French studio Xilam and based on the novel “Happy Hand” from author and screenwriter Guillaume Laurant (“Amélie”), “I Lost My Body” had its world premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. It was picked up for streaming and theatrical distribution by Netflix, where it is currently available to view in most of the world, and has since gone on to collect numerous awards including prizes for animated feature and original score from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.

Rosalie, as the creators referred to the appendage, symbolizes that missing part in all of us that we search for our whole lives. “You could look at the story of this hand as a fable about the search for oneself,” said Laurant. ”Even if many elements in our lives shape our future, and our destiny is somewhat written in advance, we all can at some point find it in ourselves to ‘dribble’ our destiny.”

In the novel, the hand communicates its existential fears through words, and in the first draft of their joint adaptation Clapin and Laurant kept that narration as voice-over. They weren’t certain about how much impact a character without a voice could have, but with the encouragement of producer Marc Du Pontavice, all of the first person, spoken accounts were stripped away.

“The only sentence directly from the hand now is the title of the film,” noted Clapin.

For the auteur, the ambition was to focus the story completely on the point of view of the hand and do so by replacing its dialogue with movement, imagery and sounds that could generate empathy for this odd protagonist.

Taking further liberties with Laurant’s text, he introduced other visual components charged with allegorical significance, such as a crane on a construction site, the igloo Naoufel builds, an astronaut that accompanies Rosalie, and, most importantly, the fly. As chaotic as destiny, the fly has the ability to see everything at once and returns throughout the story to both link and provoke life-altering occurrences.

Since the hand engages with the world through touch, Clapin also added a sensorial vehicle for Naoufel to relate to his surroundings: The sounds he recorded as a child back home in North Africa, which act as sonic tendons attaching his past to his mind.

It’s also sound that reconnects the young man to the here and now in a key sequence, when he meets love interest Gabrielle (Victoire Du Bois) over an apartment building intercom.

As a discreet personal note, Clapin embedded himself in Rosalie’s appearance. “The hand has a birthmark between two fingers, and I used to have the same exact birthmark when I was a child. I put a piece of me inside the movie,” said the director.

“Metaphorically there was something very strong about the fragmentation of ourselves, about the fact that we don’t control everything about our own identity,” noted Du Pontavice. He sought out Clapin upon reading Laurant’s novel. The mission was to test whether or not the language of cinema would be strong enough to make an audience feel empathy for a character that only has five fingers to express itself.

Du Pontavice didn’t want to work with a filmmaker who had already made a feature, concerned that most animated films are family oriented. “I had to find someone that was willing to approach the medium in a very adult way. It’s pretty much in the world of shorts that you can find those directors,” explained the seasoned producer.

Clapin’s shorts — 2004’s “Backbone Tale” (Une histoire vertébrale), 2008’s“Skhizein,” and 2012’s “Palmipédarium — are darkly philosophical examinations of the dysfunctional relationship between the physical body and the soul.

Those bite-size gems reminded Du Pontavice of the tales by Japanese writer Haruki Murakami in the way they seamlessly blend fantasy and reality. “For him, fantasy is not the opposite of the real, fantasy is actually born from the reality,” he said of Clapin’s style.

“I like to talk about reality, but to talk about reality, I need a point of view that’s external to reality, and this external point of view is the fantastical. It makes visible things that are usually not,” said Clapin.

The Academy Awards are fast approaching and Oscar pools are being organized. Let our film critics Kenneth Turan and Justin Chang help you analyze the major categories with their predictions.

But even with a built-in thematic affinity for the existing material, Clapin knew he had to invent a new approach to follow the charmingly bizarre character at the film’s center. Du Pontavice notes that Clapin’s cinematic language aligns aesthetically with live action, but the filmmaker’s poetry requires him to draw, as opposed to directing actors.

Early on, Clapin decided to begin the creation of the film using CGI in order to build realistic environments around the characters, especially in relation to the hand. “I wanted the hand to be tangible, and CG gave it real volume. Even when you draw 2D animation on top of the CG template you can feel the real depth in the shape, it’s not flat,” he said. However, fully rendered CG animation feels cold, the artist believes, so fusing both techniques resulted in a much more immersive outcome.

For the final version, a hand-drawn universe was crafted to elevate the look of the CG images with pictorial stylization that imbues the world with a sense of poetry. And a handcrafted hand emerged.

First impressions matter, so Clapin ensured that how the hand’s on-screen introduction was shot instantly placed the viewer inside its worldview as it embarks on a perilous journey.

“In the first sequence, for example, when we follow the hand, the camera is very close to it. We discover the world as the hand does, with the tips of its fingers, and we are not showing anything else that the hand can’t see,” explained Clapin. “The audience is like this hand, in a sense, and has no more information than it does. When the hand first comes to life, it’s like you are witnessing a new birth.”

Nonverbal as the faceless star is, its longing and innermost sentiments become audible thanks to Dan Levy’s transfixing score. Like a blanket knitted from astral notes that connect us to the metaphysical, his electronic harmonies lend spirituality to the singular project. “He wanted the music to help bring this hand to life and to share the emotions that it has lived through,” said the composer.

Keen on using synthetic music, Clapin wanted sirens and glissandi. He spoke to Levy more about sound design rather than musical themes. “He didn’t want us to recognize the instruments, but I thought that from time to time you had to hang on to familiar sounds like the flute or the strings,” Levy said.

Balancing the hand’s epic urban adventure with intimate notes of pain and affection required a conscious understanding of the movie’s psychological landscape.

Levy assigned an instrument to each relevant aspect of the story: the arpeggiator symbolizes the mechanics of destiny, the flute stands for Naoufel’s childhood, the love between Gabrielle and Naoufel is signified by the strings, and the three synth notes (G / C / B) represent memories. “For the memory sequences we preferred to mute the sound and leave certain images with only the music,” Levy added.

“I thought of this as providing different paths, different readings of the film,” he said about the multi-faceted emotional dimension of his atmospheric compositions. “There are the bright and most painful past, the dizzying present, and the reconciled future.”

Emotions as complex as those Clapin and his collaborators convey are seldom depicted in animation with a mature perspective. As “I Lost My Body” virtuously demonstrates, animation is not a singular genre but a medium that can operate in service of any cinematic category.

Du Pontavice credits Oscar voters for nominating a feature that’s not aimed at young audiences and crawls at its own narrative pace. Distinct from the other four family-oriented contenders (fellow Netflix title “Klaus” and the wide releases “How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World,” “Missing Link” and “Toy Story 4”), not solely for its content and purposeful mix of CG and 2D animation but also for its unconventional dramatic arc, Clapin’s film pushes artistic boundaries one digit at a time.

“It’s a nonlinear story that usually only live action dares to build. It’s a story that mirrors the complexity of the human mind. That’s why this film is so grand, and so different from the rest of current animation productions,” the producer added.

“We are considered by the academy members to be competitive in the same category. That’s a real sign that people like diversity, even in animation.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.