An actor’s heart problems highlight health insurance concerns amid SAG-AFTRA strike

The SAG-AFTRA strike is showing how industry uncertainty leads to actors losing their health insurance or not qualifying in any given year.

- Share via

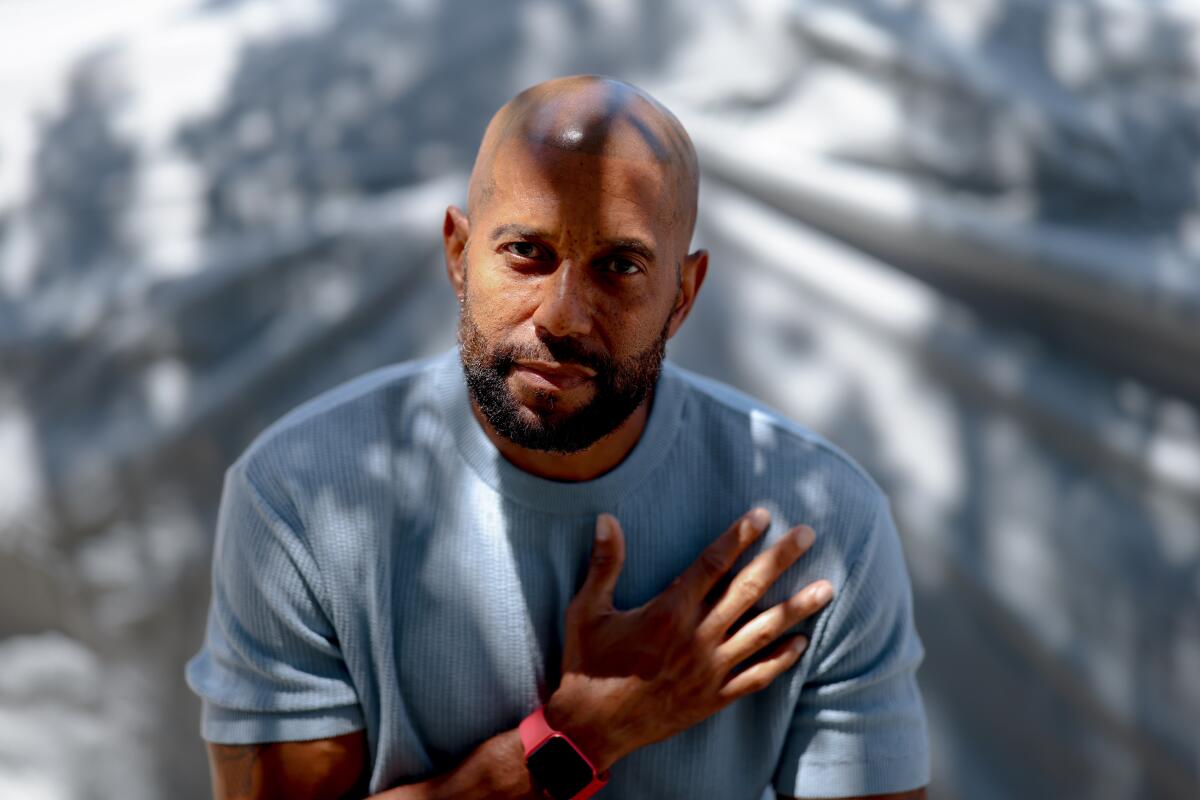

When Brooklyn McLinn nearly died of a heart attack in his kitchen, he felt a sense of peace that his health troubles — the open-heart surgeries, the pacemaker, the fear of the next big one — could finally be over.

This is the sentiment the actor and former college basketball player, 50, has after surviving two heart attacks, a stroke and a heart transplant. The first heart attack happened a few years earlier while playing basketball in Los Angeles in 2016. He was home taking a quick break from filming as a cast member for Tyler Perry’s “The Haves and Have Nots” before he flew back to Atlanta.

But the heart attack changed everything. He couldn’t go back to work and at the time he had naivelystopped paying for his insurance under the SAG-AFTRA Health Plan. McLinn’s life was almost cut short due to his heart trouble. Without his health insurance, he wouldn’t be alive today.

SAG-AFTRA has approved a deal from the studios to end its historic strike. The actors were on strike for more than 100 days.

“It really wasn’t a lot of money but in my mind I’m wasting money because I don’t use the insurance and you’re trying to hold on to every dollar because you don’t know when the next job is coming,” McLinn said. “I was thinking more in scarcity and lack , like I better hold on to every dollar as opposed to I’m gonna have some insurance to take care of myself just in case.”

Thousands of SAG-AFTRA members joined Writers Guild of America members earlier this month in striking together for the first time since 1960. The last actors’ strike was in 1980 , back when the union sought profit - sharing from studios over videocassettes and premium television like HBO. The current SAG-AFTRA strike is focused on streaming residuals and artificial intelligence and has illuminated how the uncertainty of the industry leads to actors losing their health insurance or not qualifying at all in any given year.

When SAG-AFTRA members work, companies report their qualified earnings and how many days they worked to the SAG-AFTRA Health Plan. Companies are also responsible for contributing funds to the health plan. Right now, the two ways members can qualify for a year of health coverage are working eligible jobs for 102 days or earning $26,470 annually. Under the plan, members pay their premiums every three months. Individuals pay $375 each quarter for their coverage. Plan members covering themselves and a dependent pay $531 while members with two or more dependents pay $747.

SAG-AFTRA officials said 86% of their members do not earn enough to qualify for the health plan.

Workers in film and TV, most of whom are pro-union, have been trying to make ends meet amid a dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers.

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, national executive director for SAG-AFTRA and chief negotiator for its union, said he anticipates there will be “a substantial impact” for members on strike being able to keep or qualify for health insurance coverage since they cannot work.

“It’s not automatic by virtue of just having a job on a project or being a member of the union,” Crabtree-Ireland said. “You have to be mindful and make sure you’re earning enough to qualify and that’s a real source of anxiety and concern for many members.”

Major points of contention for SAG-AFTRA members include self-taped auditions, how AI may be used in the future, and wanting a third-party company to measure the success of shows and that residual payments be tied to how they perform.

SAG-AFTRA is also asking for an increase in pension and health plan contribution caps but the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers has not offered the substantial increase they’re looking for. SAG-AFTRA officials have not disclosed the exact amount that AMPTP offered. The SAG-AFTRA proposal calls for money that goes above the contribution cap to either go to the pension and health plan or directly to the performers. AMPTP has rejected this proposal.

For McLinn, heart problems seemed inevitable. His father and grandmother both died from heart attacks. He was able to get to the hospital in time after his first heart attack. The SAG-AFTRA Health Plan allowed him to make payments again so he would have coverage. He talked to multiple doctors after his heart attack. Some encouraged him to keep taking heart medication while others said there was nothing they could do. Eventually, he found a doctor at USC who suggested he have open heart surgery. McLinn had to have the surgery in 2017 and again in 2018.

McLinn was starting to panic about not being able to work while recovering until his residuals came in. He booked a job with a McDonald’s commercial and acting in shows like “Goliath” and “black-ish.” He also landed a recurring role in the Marvel show “Cloak & Dagger” as Andre Deschaine, also known as D’Spayre, who McLinn says passes his pain on to other people.

“Things that I thought were done, like a commercial might have got brought back after it hadn’t been playing and so I got paid residuals again, a TV show that I had done re-aired,” McLinn said. “Those residuals were instrumental in helping me keep the insurance.”

As SAG-AFTRA members join writers on picket lines, the fallout will disrupt Hollywood film and TV productions worldwide. ‘There’s going to be blood in the water,’ said one analyst. ‘This will not end well.’

His second heart attack knocked him to the floor of his kitchen in 2020 while he was on the phone with his mother. McLinn said he kept pausing during the conversation because he felt himself getting increasingly hot. When his mom suggested he sit down he suddenly felt like “somebody had dumped a bucket of water on me” and he started sweating profusely. He didn’t think he was having a heart attack but he felt his head become heavy with sleepiness as his mother called 911.

“All I was thinking was I could just go to sleep and be done with all this because it didn’t hurt,” McLinn said. “I was like, ‘Man, I’m tired of living my life with a bad heart’ ... I could just go to sleep; nobody will say I didn’t try.”

The paramedics urged him to stay awake — or else he might not wake up again. He flatlined on the way to the hospital but paramedics were able to shock him back to life.

Disabled workers say they’re a canary in the coal mine: “If disability is on the caboose of the writing chain, we will be the first people to get pushed out.”

He was given a pacemaker before he left the hospital. In early 2021, McLinn had a heart transplant but it took time for him to consider it because he didn’t think he would ever need one.

“I struggled with the idea you’re waiting for somebody to die,” McLinn said.

He had the surgery but was then in the hospital for two months to recover from a stroke he had during the procedure. He couldn’t use the left side of his body and was unable to brush his teeth, wash his face, bathe himself or go to the bathroom on his own.

“I know most men are ego - driven and prideful , and it just broke me all the way down to the point where I couldn’t do anything for myself,” McLinn said. “I’m just like , man, this is my life, like, oh my God, I should have just died on the floor. You have so many thoughts. And the nursing staff was awesome. They’re like, ‘Look, this is our job, this is what we do … you’re going to get better.’”

Nearly a year after he got out of the hospital , McLinn received a letter from the SAG-AFTRA Health Plan stating that his coverage was running out at the end of the month.

If SAG-AFTRA members lose health coverage because they did not work enough days or meet the earnings threshold, they qualify for continued coverage under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, or COBRA. While they would have insurance for 18 months, it’s at a much higher price and due monthly. Individuals today pay $1,005 per month. People covering themselves and one dependent would have to pay $1,784 each month, and members covering two or more other people would have to pay $2,501 monthly.

Longtime members who have qualified for the SAG-AFTRA Health Plan coverage at least 12 times can elect to pay a reduced monthly amount for COBRA if they made at least $20,400 for up to a year. Members who have qualified 20 times or more and made at least $20,400 can be eligible for 18 months of COBRA coverage at a lower price.

When McLinn was on the verge of losing his health insurance, he called the plan’s membership phone number immediately. He needed the insurance to continue getting his medication that helped prevent his body from rejecting his new heart. He was also cleared to go back to work.

“They were pretty stern on their line of ‘well you haven’t earned enough money, ’” McLinn said. “And I was like, ‘I understand that, I’m just looking for an extensionbecause this is what happened, you guys are seeing the hospital bills.’”

They still said no.

As SAG-AFTRA members join writers on picket lines, the fallout will disrupt Hollywood film and TV productions worldwide. ‘There’s going to be blood in the water,’ said one analyst. ‘This will not end well.’

One of McLinn’s friends encouraged him to reach out to the SAG-AFTRA Foundation for help. The foundation asked McLinn to try calling the health plan again, but this time they said if he were disabled and unable to work anymore then they might be able to help. Other than that , there was nothing they could do.

McLinn had to get coverage under COBRA but was able to get his health insurance covered by the SAG-AFTRA Foundation and the Motion Picture & Television Fund. He had six months to earn enough again to qualify for the lower-priced SAG-AFTRA Health Plan. He booked a pharmaceutical commercial and then a recurring role as Doc Hightower on Peacock’s show “Bel-Air . ”He was grateful that work picked up again.

“To have to pay $1,000 a month, as a regular citizen, I feel for people that actually have to do this,” McLinn said. “We have this foundation and we have the Motion Picture Fund that are able to provide some assistance to help through these times…. I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say, for that period, I feel like the foundation threw me a lifeline.”

SAG-AFTRA members can turn to the SAG-AFTRA Foundation’s emergency assistance program when they need help. The foundation has to raise money through grants and donations to fund the program and limits each member to receiving $6,000 in assistance over their lifetime. Members are also not automatically given help under the program and can be denied aid.

Cyd Wilson, executive director of the SAG-AFTRA Foundation, said the organization normally processes between 15 and 20 emergency assistance applications in a week. Since the strike began they’ve been processing roughly 35 applications a day.

“It’s very reminiscent of what happened during COVID for us, it feels like deja vu all over again,” Wilson said. “When you have a significant number of people that are already living paycheck to paycheck, and they’re working a job as an actor, plus maybe driving Uber and a bartending job at the same time … the slightest bit of change in their income, even if it’s losing $1,000, can be the difference between their struggling and their not being able to survive.”

Disabled workers say they’re a canary in the coal mine: “If disability is on the caboose of the writing chain, we will be the first people to get pushed out.”

Wilson and others who review the applications typically see people who are facing financial distress such as being months behind on utility bills, on the verge of evictionor facing medical and dental bills they cannot pay. Wilson said the foundation looks at each application’s circumstances to determine what to give. When there are health issues involved, applicants may receive more than the lifetime limit of $6,000.

Members who applybecause of medical distress often have chronic health issues they need help with, such as undergoing cancer treatment, needing dialysis or recovering after a heart attack. Some also need dental work. Wilson said members who apply for emergency assistance may have the SAG-AFTRA Health Plan but they cannot cover the extra costs for their care.

The SAG-AFTRA Health Plan notes that members who lose their coverage have potential options including: getting covered through the Artists Health Insurance Resource Center or the Entertainment Health Insurance Solutions; using Medicare if they qualify; applying for Medicaid, the joint state-federal health insurance program for low-income and disabled people; getting insurance through a state insurance marketplace; or getting on their partner’s health plan.

California’s budget from the legislature provided $2 million for Covered California, the state’s health insurance marketplace, to provide subsidies to people who lose their health insurance coverage as part of a labor dispute. The subsidies will help offset the cost of medical care and monthly health insurance premiums.

Craig Tomiyoshi, a spokesperson for Covered California, said in an email statement that they are not aware of any SAG-AFTRA members who have lost health coverage, but if someone has they should contact them right away.

“Covered California is aware of the SAG-AFTRA strike, and should the labor dispute necessitate action, Covered California will work with individuals to help them enroll in a plan with the appropriate subsidies,” Tomiyoshi said. “As these enhanced subsidies will only be available once an individual loses their employer-based coverage, we are monitoring this ongoing situation with this in mind.”

McLinn said part of the problem is people assume it’s all wealthy people out on the picket lines but that’s far from the truth. He pointed out that people do not see the background actors, stand-ins, stunt performers, camera operators and other people who make television and films happen and need residuals to stay financially afloat.

For now, McLinn says his health issues have led him to be more aware of how he’s feeling every day and grateful he can work, walk and take care of his nephew. He has been out on the picket line and has been able to do commercial work while the strike continues because the union’s agreement with advertisers is separate from its television, theatrical and streaming contracts. But he said the industry is not set up fairly as actors and other SAG-AFTRA members try to get paid and stay in a business where people are often working to be seen for the right opportunities.

“I hesitate to say you got to believe in something unseen, but really, that’s what it is,” McLinn said. “But how do you tell somebody who’s struggling? They don’t want to hear that ... this business is not set up for the faint of heart.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.