High-profile streamer Quibi is shutting down after subscriber struggles

- Share via

Less than seven months after Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman launched Quibi to remake the business of short-form video, the nascent streaming service is shutting down, ending one of the most ambitious and closely watched Hollywood start-ups in years.

Katzenberg and Whitman told investors Wednesday afternoon that Quibi, which raised $1.75 billion to tackle the growing digital video market, will wind down after failing to attract viewers willing to pay to watch its shows, according to people familiar with the matter who were not authorized to comment.

Hollywood-based Quibi, which employed 265 people as of April, plans to use its remaining cash of about $350 million to pay back investors, sources said, a stunning turn of events for a company that promised to transform the entertainment industry.

Quibi said in a statement Wednesday it will close down the business and begin the process of selling off assets over the coming months.

“The world has changed dramatically since Quibi launched and our standalone business model is no longer viable,” Katzenberg said in the statement. “I am deeply grateful to our employees, investors, talent, studio partners and advertisers for their partnership in bringing Quibi to millions of mobile devices.”

Quibi, short for “quick bites,” launched in early April with a bold bet on shows and movies with episodes lasting 10 minutes or less. The company charged $5 a month for people to watch with ads and $8 for a commercial-free version. Backers included major entertainment and media companies such as Walt Disney Co., ViacomCBS, AT&T’s WarnerMedia, Sony Pictures Entertainment and China’s Alibaba Group, along with more traditional financiers such as JPMorgan Chase & Co., Goldman Sachs and Madrone Capital.

The idea was that the platform would stand out from free rivals like YouTube, TikTok and Snapchat by bringing Hollywood-level production values to short-form content. Quibi shows featured celebrities such as Chrissy Teigen and Liam Hemsworth.

The strategy failed. Launching amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, Quibi quickly fell out of the top ranks of app store sales charts as its shows struggled to draw subscribers. The service also missed key viewership targets for advertisers.

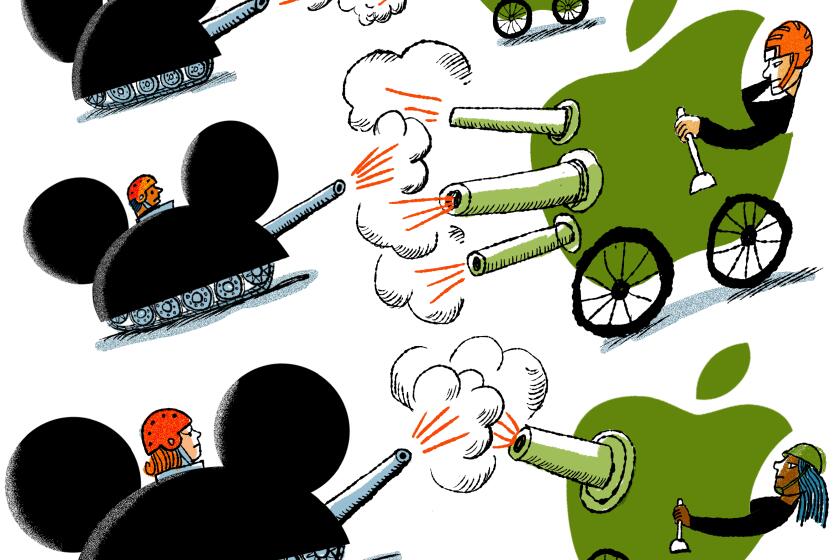

Disney takes on Netflix, as HBO Max, Peacock, Apple TV+ and Quibi prepare to enter the streaming fray. Not all will be able to thrive in the increasingly crowded market, analysts warn.

The decision to shutter Quibi — first reported by the Information and the Wall Street Journal — is the most spectacular failure yet in the media industry’s streaming wars era, which has seen the launch of well-backed services including Walt Disney Co.’s Disney+, AT&T Inc.’s HBO Max and Comcast Corp.’s Peacock. Though each streamer has followed a different strategy, all are meant to keep their parent companies relevant at a time when Netflix continues to spend heavily on shows and movies for its platform.

Many analysts had been skeptical from the start that Quibi would be able to succeed. Previous efforts to capitalize on young viewers’ appetite for online video have collapsed, including Verizon’s Go90, which shut down in 2018. Hollywood history is rife with examples of bold attempts to shake up the business that flamed out, including Relativity Media and Open Road Films.

Katzenberg was attempting to defy the most successful formula used by virtually every start-up, from cable TV channels to Netflix. Such platforms got their start by programming old movies and TV show episodes. Once these businesses attracted viewers, they began adding original shows to their lineups.

In contrast, Quibi asked subscribers to pay for an unknown batch of original content. The assumption that people would pay to be entertained by a splashy celebrity, like Teigen, turned out to be wrong, particularly when the same celebrities reveal their most intimate moments on their own Instagram feeds.

The abrupt retreat is a major blow for Katzenberg, a relentless and savvy businessman known for co-founding DreamWorks Animation, the studio behind “Shrek,” “Kung Fu Panda” and other franchises. He sold the Glendale-based studio to NBCUniversal for $3.8 billion in 2016.

The billionaire executive, who led Walt Disney Studios through its 1990s animation renaissance, acknowledged before the launch of Quibi that his concept was a big gamble.

Still, he and Whitman exuded brash confidence as they positioned Quibi as the next big thing.

“We’re all dogs and we marked enough territory in our life,” Katzenberg told the Los Angeles Times last year. “Here is the single thing above all else that bonds us and binds us together. ... We have a bottomless well of the need to win and whatever it takes us to win.”

Quibi’s downfall also represents a setback for Whitman, who joined Quibi as its chief executive after serving as CEO of Hewlett-Packard and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. She was previously CEO of EBay from 1998 to 2008. Whitman, who ran unsuccessfully as a Republican candidate for California governor in 2010, has been floated for a Cabinet position in a potential Biden administration after the presidential election, according to Politico.

In recent weeks, Katzenberg and Whitman tried to sell Quibi to media and tech companies including NBCUniversal, WarnerMedia and Facebook, according to people familiar with the matter who were not authorized to comment. But those efforts failed to gain much traction, the sources said.

Katzenberg and Whitman declined interview requests.

Katzenberg delivered the grim news in a heartfelt call with distraught staffers Wednesday afternoon, invoking the song “Get Back Up Again” from “Trolls,” the 2016 animated movie produced by his former studio, according to a person familiar with the meeting.

The company last month began seriously exploring strategic options, including a sale or taking Quibi public through a special purpose acquisition company, a popular method of raising money without a traditional IPO.

With no takers, Katzenberg had little choice but to cease operations. The lack of interest among potential buyers was partly because Quibi licenses and does not own the content it puts on the app. Another problem is Quibi’s lack of hits, though the company recently won two Emmys for its drama #FreeRayshawn.

“When you’re valuing that content, you can only judge content based upon audience reaction,” said Eunice Shin, partner at Prophet, a brand and marketing consultancy. “So far, this content has been live and put out there, and it hasn’t resonated with audiences.”

Any buyer would also have taken on the liability of a legal battle over its “turnstyle” technology, which lets the image rotate depending on how users hold their devices. Rival Eko has accused Quibi of lifting its intellectual property, a claim that Quibi says is baseless.

Then there was the COVID-19 pandemic. Part of Quibi’s pitch to viewers and investors was that millennials would watch Quibi’s shows during “in-between” moments, like waiting in line for coffee and riding the subway to work.

Katzenberg, in interviews, said the coronavirus outbreak throttled the app’s strategy by eliminating such activities for months for millions of people.

“The circumstances of launching during a pandemic is something we could have never imagined but other businesses have faced these unprecedented challenges and have found their way through it,” Katzenberg and Whitman wrote in a joint post on Medium. “We were not able to do so.”

Another problem for Quibi was that people already had plenty of content from social media companies including Instagram and TikTok to keep them occupied during idle moments.

Usage of streaming services such as Netflix surged during the public health crisis. Disney+ hit a stellar 60 million subscribers thanks in part to offerings such as its “Hamilton” movie, which debuted on the $7-a-month service for the July 4 weekend.

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.