Hollywood is still groveling to China. It’s not really working anymore

- Share via

This is the Feb. 8, 2022, edition of the Wide Shot newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox.

For decades, Hollywood executives portrayed their strange relationship with China as being mutually beneficial. Studios got to access an enormous and fast-growing market, and China’s citizens got to enjoy America’s rah-rah blockbusters. All it cost was a little censorship and groveling.

But as the U.S. film business chased the new foreign cash pile, the Chinese Communist Party viewed entertainment as part of a long-term battle for global cultural power.

And after decades of Hollywood studios kowtowing to an authoritarian government, it’s become increasingly clear that China is gaining an advantage in that fight, while using weapons supplied by America.

Blockbusters based on Marvel superheroes and Transformers toys built up China’s burgeoning cinema business. Hollywood directors taught filmmakers overseas how to make their own big-screen spectacles. China’s richest players bought stakes in U.S. production companies, including Steven Spielberg’s studio.

Today, China’s unspoken message is, “Thanks. We’ll take it from here.”

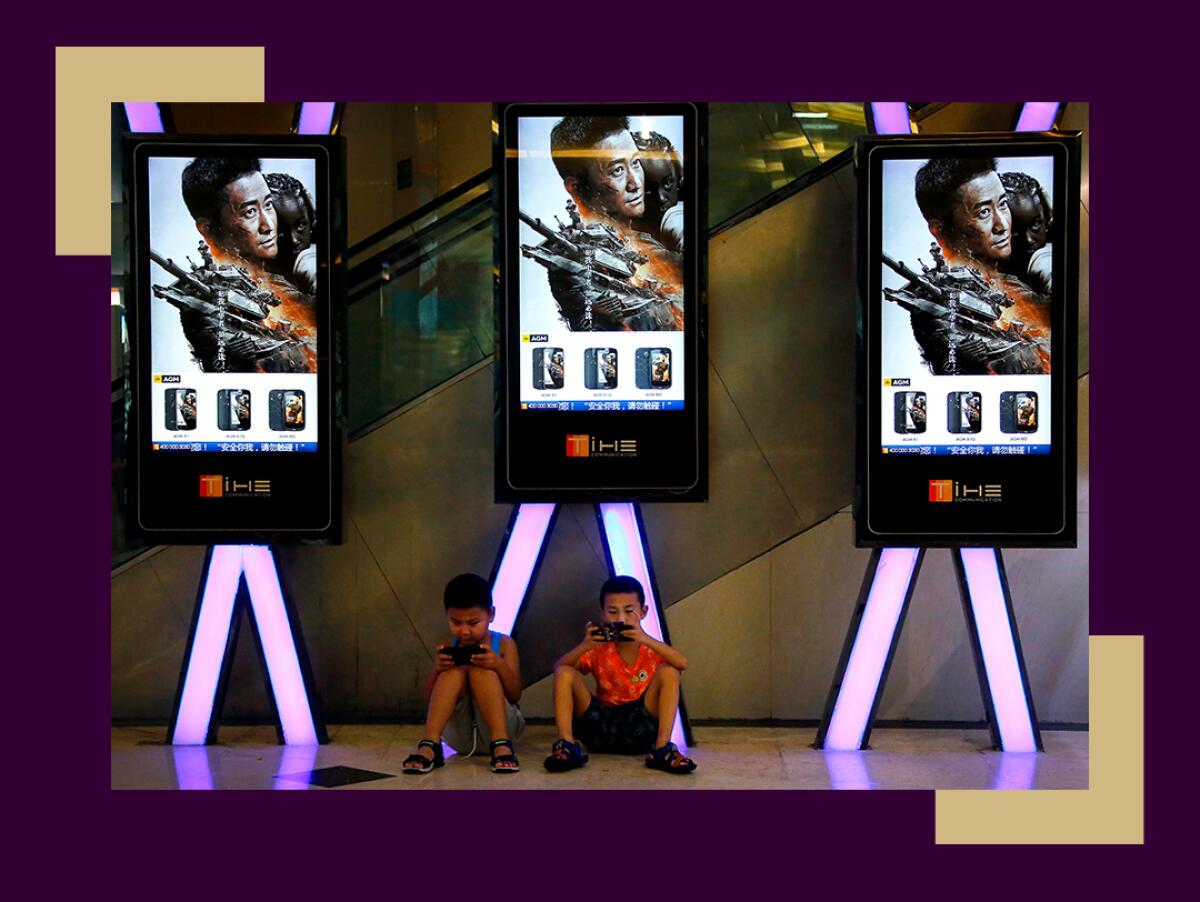

The bounty of Chinese box office sales that went into studio coffers has slowed to a trickle as the nation’s own productions, made to serve party interests, dominate theaters. The nation’s current No. 1 movie, a patriotic action film titled “The Battle at Lake Changjin II,” has grossed nearly $400 million so far, according to film consultancy Artisan Gateway.

Meanwhile, U.S. movies and imports from other countries took up a meager 15.5% of China’s ticket sales last year, compared with 36% in 2019, according to Artisan Gateway.

The change is remarkable, considering that China once worried about Hollywood films accounting for as much as 50% of annual ticket sales in the country.

Hollywood movies that two years ago would have been assured Chinese releases haven’t been granted entry, notably Sony’s “Spider-Man: No Way Home” and Marvel’s “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings,” the latter of which was made with China in mind.

Many films that did get their coveted government approvals in recent months fared poorly. Warner Bros.’ “The Matrix Resurrections” made an unimpressive $13.3 million in China. Disney’s “Encanto” made even less ($11.7 million). And if a movie release is delayed in China, forget it. Rampant piracy probably will wipe out its potential grosses.

The strange tale of how we got here is told in the new book “Red Carpet: Hollywood, China and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy” by Erich Schwartzel, who has reported for years on the topic for the Wall Street Journal.

Schwartzel traces Hollywood’s reliance on China to a time of economic distress for the film business. With its more than 1 billion people, China represented not just a source of box office sales but a financial bailout after the collapse of the DVD market eroded Hollywood’s healthiest profit pipeline.

But as Hollywood focused on quarterly results, China was playing a long game that it viewed in the context of thousands of years of history leading to the present day, when China doesn’t have to rely on the Avengers to draw moviegoers. A key turning point was the 2017 release of the Chinese production “Wolf Warrior 2,” which grossed more than $850 million in a single country.

“While China had started the decade leaning on the American film industry for revenue and education, the country would end it by not needing U.S. entertainment at all,” Schwartzel writes.

This comes after entertainment companies went to extraordinary lengths to appease censors. A 2012 “Red Dawn” remake was digitally reedited to change the flags of the invading enemy from Chinese to North Korean. The script of “World War Z” was altered to remove a plot point in which the zombie-causing virus originated from China. Marvel shoehorned Chinese actress Fan Bingbing into a scene for the China cut of “Iron Man 3.”

Just a couple of weeks ago, social media users noticed that “Fight Club” had gotten a new ending for its release on Tencent’s streaming service in China. Unlike David Fincher’s 1999 original, it now ends with the cops thwarting Project Mayhem’s plot to blow up buildings that contain debt records.

In the Chinese version, the movie stopped before the explosions and a text card revealed that, after being tipped off, “Police rapidly figured out the whole plan and arrested all criminals, successfully preventing the bomb from exploding.” On Sunday, news outlets reported that the original “Fight Club” ending had been restored after the backlash.

Snafus were followed by embarrassing mea culpas. John Cena last year delivered a video apology in Mandarin for referring to Taiwan as its own country while promoting “F9: The Fast Saga.” The Chinese government considers Taiwan to be a part of China.

But while studios avoided making China a villain, as Schwartzel notes, “Chinese filmmakers were not extending the same courtesy” to Americans, who in some patriotic films served as heavies portrayed as jingoistically as the Soviet boxer Ivan Drago in “Rocky IV.”

Now even the economic benefit of the China-Hollywood dance is uncertain, though some productions — “F9” and “Godzilla vs. Kong,” the latter of which was produced by Chinese-owned Legendary Entertainment — did sizable business last year.

Maybe things get better after the Lunar New Year celebrations, when China enforces a blackout of imported pictures. Still, the dominance of Chinese blockbusters in the Middle Kingdom has become a worry for studios sitting on movies that were greenlighted with $200-million budgets on the assumption that China would contribute tens of million of dollars in box office.

This is not the only time the American entertainment industry has prioritized profits while a rival took advantage. In a recent interview with Kara Swisher, former Disney CEO Bob Iger discussed the company’s former practice of licensing Disney movies to Netflix, comparing that strategy to a catastrophic foreign policy blunder. Disney movies brought subscribers to Netflix, which allowed the streamer to produce its own movies and shows.

“I woke up one day and thought, ‘We are basically selling nuclear weapons technology to a third-world country, and now they are using it against us,’” Iger said.

It’s a pretty vivid metaphor for a key moment preceding the streaming wars. It might work even better for the Hollywood-China cultural transaction.

Read the Times’ Q&A with Schwartzel about “Red Carpet.”

Stuff we wrote

— Another streaming lawsuit. “The Matrix Resurrections” co-producer Village Roadshow has sued Warner Bros. for breach of contract over the movie’s HBO Max release.

— There are still plenty of unanswered questions about Jeff Zucker’s resignation from CNN after failing to disclose a consensual relationship with a lower-ranking executive. CNN staffers grilled WarnerMedia boss Jason Kilar last week over the decision to let Zucker go, reports Stephen Battaglio.

— In the streaming era, Super Bowl 2022 commercials will be working overtime. Battaglio analyzes the challenges facing advertisers ahead of Sunday’s big game.

— Women’s Sports Network seeks to spotlight female athletes. From Meg James: “Shifting cultural attitudes and changes in TV consumption patterns have created an opening for an independent Los Angeles studio and women’s sports leagues to put a bigger spotlight on female athletes and their achievements.”

— Why the Cherokee Nation is offering rebates to film in Oklahoma. “Native American tribes are working to expand their role in film and TV production to help revitalize and diversify their lands’ economies, as well as improve representation of Indigenous people onscreen,” Anousha Sakoui writes.

— Spotify’s biggest problem isn’t Joe Rogan. It’s the company’s ambition to become the king of all audio, as Matt Pearce and Wendy Lee argue in their news analysis. Spotify sees its biggest growth opportunity in the podcast space, and Rogan’s show is a centerpiece of that strategy.

Additionally, Rogan apologized over the weekend for using the N-word in response to a viral video that compiled his utterances of the racial slur. Musician India Arie had requested her music be removed from the platform over Rogan’s comments on race. Spotify CEO Daniel Ek on Sunday apologized to staff for the controversy but strongly indicated that the service would not dump Rogan.

Docuseries demand explodes

Premium documentaries and docuseries have grown from their once niche and art-house appeal into a mainstream commercial business in recent years, with recent examples including Lifetime’s “Janet Jackson” and Showtime’s “We Need to Talk About Cosby” entering the cultural firmament.

Last week I wrote about Andrew Fried, whose Santa Monica company Boardwalk Pictures has been one of the primary beneficiaries of the doc boom, producing W. Kamau Bell’s Cosby series, as well as “Cheer” and “The Goop Lab.” Fried was arguably at the epicenter of the explosion when Boardwalk’s “Chef’s Table” got Netflix into the original nonscripted content space.

“I remember, when we would talk about shows, we would say, ‘Is this for commercial success, or do you want to get nominated for awards?’” Fried said. “And I think what we started to say, in the early days of Boardwalk, is, ‘Both.’ You can do things that are meaningful and elevated. You don’t have to choose.”

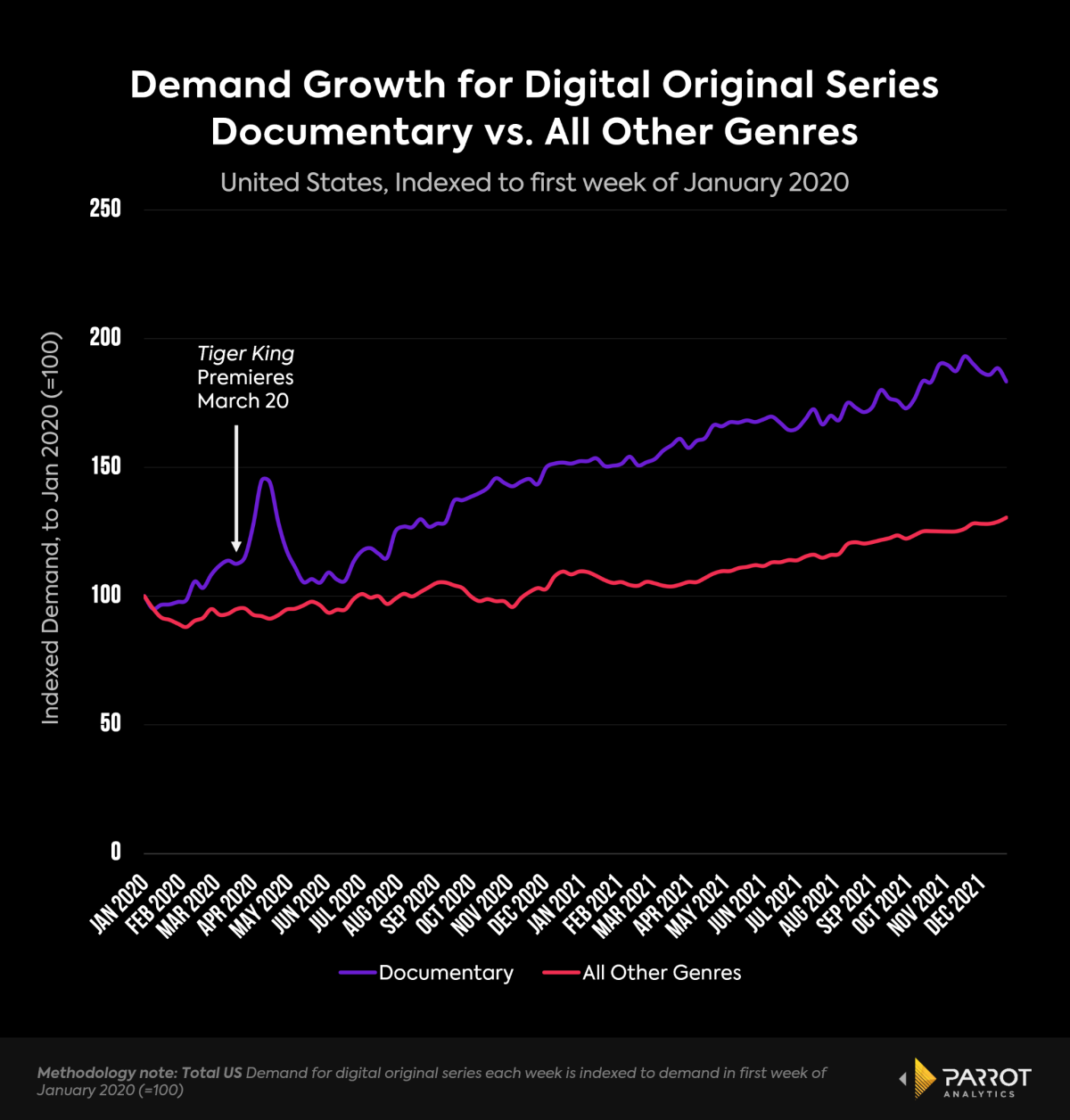

Streaming is partly to thank for the rise of the doc genre. The audience appetite has grown rapidly in the last two years, according to research firm Parrot Analytics. From January 2020 to December 2021, U.S. demand for digital original documentaries grew 83%, while average interest in all other categories of original series increased 31%, according to Parrot data.

Streaming has made documentaries on obscure subjects easier for viewers to find and watch. Popular programs appeal to viewers’ thirst for nostalgia (HBO Max’s “Beanie Mania”) as well as their interest in cults (HBO’s “The Vow”), internet culture (Netflix’s “The Social Dilemma”) and music (“Summer of Soul”).

“What we’ve seen is that docs have shifted from being art-house fare to being discovered on these streaming platforms,” said Sarah Aubrey, head of original content for HBO Max. “It has left the niche territory and really exploded into just yet another form of storytelling for people, rather than being the purview of art-house cinemas and film festivals.”

Number of the week

Spotify’s mess over Joe Rogan’s comments on COVID-19 vaccines and race opened the Swedish streamer to renewed scrutiny over how musicians are compensated for streaming, which has been a longtime beef.

While Spotify helped record labels bounce back from possible extinction by providing an alternative to digital piracy, many artists are not fans of the service. The poor economics of streaming have inspired as many #DeleteSpotify hashtags from artists as has COVID-19 misinformation.

Amid the continuing Rogan-related fallout, musicians including Max Collins of “Inside Out” band Eve6 have hit the company hard over the paltry payments they receive for their music: “our stupid band gets close to a million monthly streams on spotify,” Collins wrote on Twitter. “spotify pays out .003 cents per stream. 100% of that goes to our former label sony who is a part owner of spotify. this is why i’m mad.”

Spotify pays roughly 70% of its streaming music revenue to rights holders, primarily meaning record labels and publishers. It’s the record companies that then pay the artists. Not much trickles down, as my colleague Randall Roberts reported last year, and that’s a big part of the problem. In that piece, Midia Research analyst Mark Mulligan had bad news for artists: Streaming will not bring back the glory of the CD era.

“Streaming works for record labels,” Mulligan told Roberts. “It works for publishers. It works if you’ve got thousands or millions of songs — it all adds up. But if you’ve only got 20 or 30 or 100 songs, then it doesn’t. You need scale of catalog to benefit.”

That’s exactly why companies are spending so much money to buy music catalogs from people like Bruce Springsteen and John Legend.

The Hustle published a useful piece by journalist Mark Dent, which explains how Spotify pays out royalties and why so many artists have been angry for so many years. A key thing to understand about how Spotify’s business works is this: Spotify doesn’t pay a flat per-stream rate.

Instead, it sets aside a pool of money for rights holders and allocates those payments based on the share of streaming generated by each artist. That results in average payments that equal fractions of cents per play.

“Spotify, the world’s leading music streaming platform, has been heralded as the savior of the recording industry,” Dent writes. “But it sure doesn’t feel that way right now.”

Dent offers some potential solutions, while explaining the complications that would come with them. Could Spotify increase its royalty pool to, say, 90% of its revenue, for example? Sure, but shareholders would punish it for crimping profits. If Spotify increased its subscription fee to compensate for that increased spending, more users would jump to Apple.

As we discussed last week, most musicians can’t afford to take their tunes off the platform, which comprises 31% of the subscription-based streaming market, according to Midia Research. Nor can they forsake the exposure it gets them.

You should be reading...

— Peacock gets another crack at Olympic gold. After poor reviews for the summer games, the NBCUniversal streamer has made some major changes. Josef Adalian has a strong analysis of the company’s attempt at a redemption story. (Vulture)

— Of course I’m linking to this... Heavy metal bands find subtle notes selling fancy whiskey. Metallica, Slipknot, Gwar, Anthrax and Motörhead are branding small-batch spirits. (Wall Street Journal)

— Facebook vs. the regulators. Interesting tweet from Ben Thompson on the competitive landscape in social media: “It sounds absurd to tweet it, but the FTC really is suing an American company for eliminating competition while a Chinese company is eating their lunch.”

— The name of this interviewee is David Byrne. A fun Q&A with the Talking Heads frontman, who’s showing his drawings in New York. (New York Times)

Hollywood production

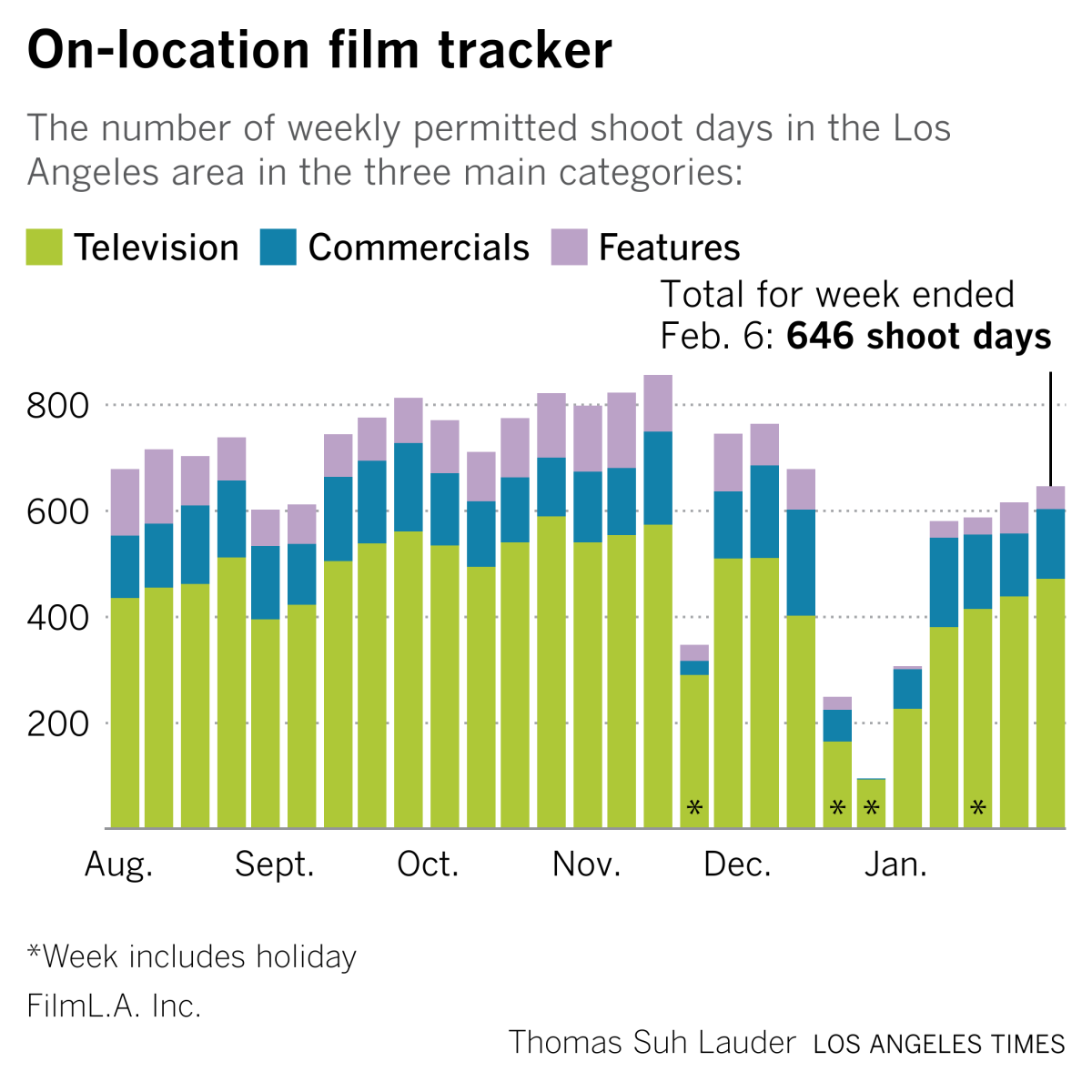

Production shoot days continued to recover from a post-New Year’s lull, according to the latest data from FilmLA.

Finally...

Not everyone’s going to be comfortable seeing live music yet. But going back to concerts has been an invigorating experience for me. On Saturday my dad and I saw prog-metal titans Dream Theater play in downtown Los Angeles, touring on their latest album, “A View From the Top of the World.” My ears were ringing, and I was smiling. Dream Theater’s compositions tend to be a tad long-winded, but if you’ve read this far, maybe that’s not a hurdle for you.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.