The Wide Shot: Why every media company thinks it has a ‘flywheel’

- Share via

Once you’re aware of a popular corporate buzzword, it’s impossible to escape. In media and entertainment spheres, “flywheel” has become the going term, used to describe everything from Netflix to Walt Disney Co. to World Wrestling Entertainment.

But why “flywheel”? And why now? The term has dethroned “funnel” as the aspirational executive metaphor of the moment — but how is it different from “synergy,” that byword of mergers of yesteryear?

While we’re at it, what is a flywheel, anyway? In mechanical engineering, it’s an actual wheel that stores kinetic energy and has been key to the workings of tractors, steam engines and foot-operated sewing machines.

Applying the flywheel concept to business — where it’s typically used as a metaphor for different parts of a company building unstoppable momentum — is not a new idea.

Business consultant and researcher Jim Collins coined the term in his 2001 book “Good to Great” and taught the concept to executives at Amazon.com in Seattle around the same time. Jeff Bezos and the Amazon execs ran with the idea and created a drawing representing it; the idea, in essence, is to set up a virtuous cycle. (So for Amazon, lowering prices improves the user experience, which boosts traffic, which attracts third-party sellers, which improves selection, which improves the user experience, etc.)

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Naturally, the idea is attractive to legacy media organizations trying to emulate the tech world by going direct-to-consumer through their own streaming services.

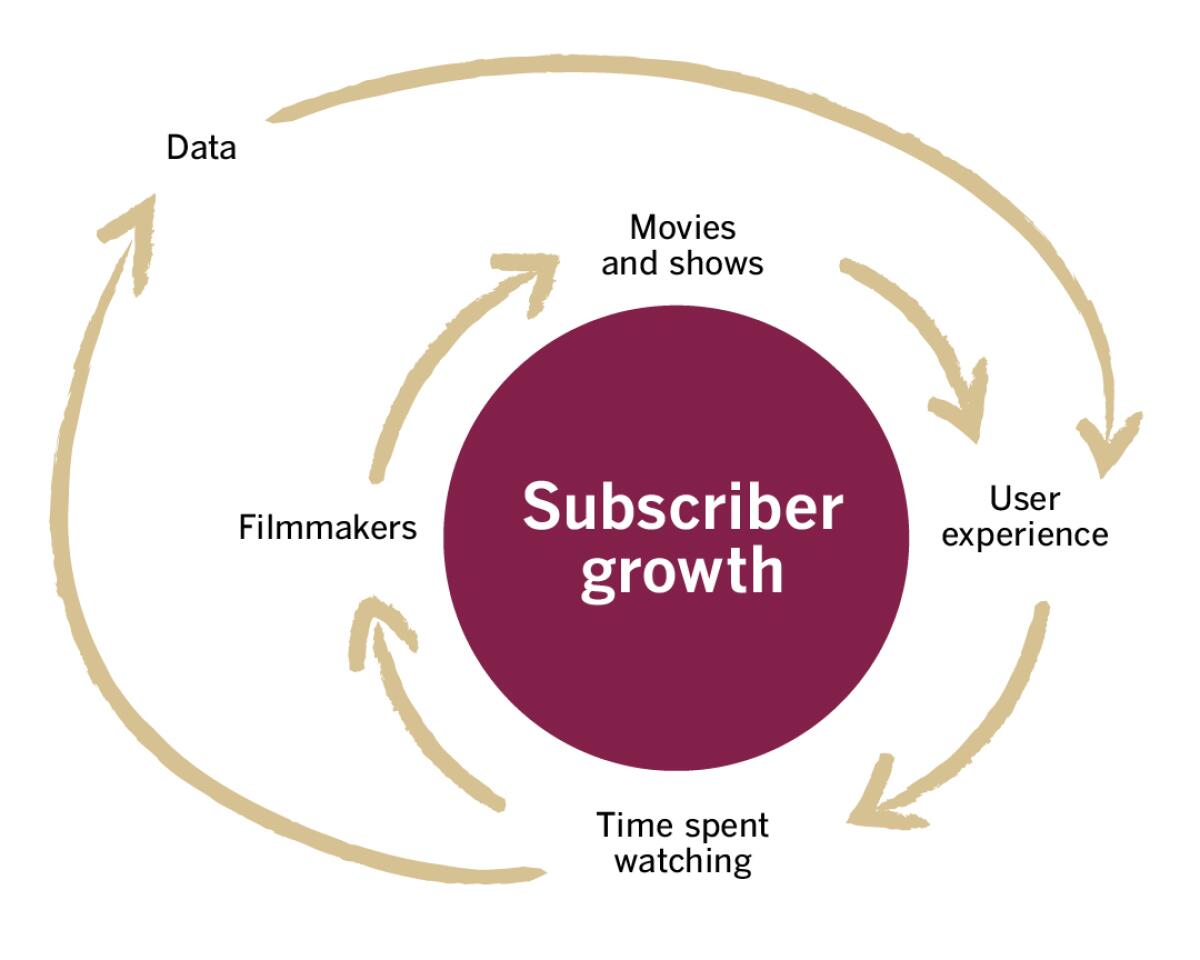

Pivotal Research analyst Jeff Wlodarczak described Netflix’s business like this last year: “Subscriber growth is the flywheel that drives a virtuous cycle for [Netflix] as the larger their subscriber base grows the more they can invest in original content which increases the target market for their service.”

Here’s what I came up with to illustrate what a Netflix flywheel might look like — beyond the idea of subscription revenues fueling film production — by substituting parts of Amazon’s diagram with aspects of Netflix’s business.

So is this just the latest buzzword to lose its meaning through overuse (like “synergy,” “franchise” and “ecosystem”)? I got ahold of Collins to ask him about the term’s ubiquity and where people tend to get it wrong.

A key point, he said, is that the steps of the flywheel can’t just be individual actions by different parts of the business. They have to lead to one another in a cause-and-effect relationship.

“What I tell people is, ‘Don’t tell me you have a flywheel; show me how your flywheel works and diagram it out for me,’” Collins said. “I want you to show me the logic of your momentum. If you can’t do that, you don’t have a flywheel.”

Usage varies throughout the industry.

Spotify Chief Executive Daniel Ek is one frequent flywheeler.

“With more reach comes more content and with more content, especially content unique to Spotify, there comes more opportunities to monetize,” Ek said during his October earnings call. “And that interplay is super important because it’s really the foundation of our flywheel. And that flywheel continues to accelerate faster with every new user and creator that comes on our platform.”

Disney Media and Entertainment Distribution Chairman Kareem Daniel spoke during the company’s December investor day about “theatrical exhibition’s ability to help establish major franchises that are at the heart of our Disney flywheel.”

Walt Disney wouldn’t have called his company a “flywheel” when he opened Disneyland in the mid-1950s. However, Disney’s 1957 drawing that illustrated his company’s various businesses looks remarkably similar to what Collins and Amazon described decades later.

WarnerMedia’s Studios and Networks chair Ann Sarnoff uses the flywheel metaphor when describing how various parts of the group’s business work together to plan a franchise, such as DC. The studio’s “The Batman,” coming in 2022, will connect to the Gotham P.D. series for HBO Max and the “Gotham Knights” video game, with the hope of growing the collective fan base, she said.

How is that different from “synergy”? The idea, she explained to me last week, was helpful when trying to make the various divisions of Warner Bros. and the broader WarnerMedia group work more effectively together and plan content strategies in advance, whereas it had previously been rigidly siloed.

“The reason I like the flywheel is because it shows motion, whereas ‘franchises’ can be something that [is] in motion or sitting on a shelf,” she said. “I wanted people to get the sense of motion and that by people working together they could create bigger motion, and everybody benefits from it. More importantly, the fanbases grow as a result.”

Sometimes flywheels break down or never get started, as LightShed Partners analyst Brandon Ross noted when WWE threw in the towel on its WWE Network streamer. “Not all DTC has a flywheel,” Ross said. “Disney is a good example of one that does. WWE thought they had one. They did not.”

At least WWE has Bad Bunny (hat tip to The Times’ Jen Yamato).

Not everyone is a convert to the flywheel gospel (see the Entertainment Strategy Guy‘s deep dive).

Gene Del Vecchio, who teaches marketing at USC’s Marshall School of Business, said the metaphor’s emphasis on self-perpetuating momentum obscures the amount of effort that goes into creating hit film after hit film. There’s a reason people in Hollywood tend to describe each film and TV show as its own startup.

“This industry is one in which the product has to be constantly reinvented,” Del Vecchio said.

Collins is aware of that and notes that the concept only works if the business is executing well at every turn of the wheel.

“It’s not a mechanical system; it’s a creative system,” he said. “You’ve got to execute on every key component because if you don’t, the whole flywheel stops.”

Ryan Coogler’s Disney deal

Disney lost some of its top TV showrunners to Netflix in the last several years, including Kenya Barris and Shonda Rhimes, whose pact with the streamer paid off big time recently with “Bridgerton.”

But Disney on Monday showed it’s still very much in the game, signing Ryan Coogler’s Proximity Media to a five-year TV production deal. The agreement is more expansive than the typical Disney TV deal because it enables the “Black Panther” director to produce shows for the entire company, including Disney+. Coogler is kicking things off with a Disney+ Marvel series set in Wakanda.

Number of the week

So much of the focus during the streaming wars has centered on $10-a-month subscriptions that it’s easy to forget a simple principle: People will watch a few ads if it means they can save money.

Ad-based tiers so far appear to be working for Peacock, which strut its stuff during Comcast Corp.’s earnings call. The Philadelphia cabler said Thursday that Peacock had reached 33 million signups, rising from 22 million in the prior quarter.

It’s a mystery how much people are actually watching the shows, but the move of “The Office” from Netflix clearly helped. Parrot Analytics said U.S. “demand” for “The Office” shot up 39% during its first three days on the sitcom’s new home. Peacock should also get a boost in March when WWE comes to the platform, giving fans their wrestling action for half what they were paying WWE’s own streaming service.

Whether Peacock would work was a big question mark last year, especially after the delay of the summer Olympics, the would-be cornerstone of its promotional push. NBCUniversal CEO Jeff Shell says he’s “pretty confident” the Olympics in Japan will happen this year.

But in a year in which some of our readers actually miss the simplicity of the cable bundle, advertising-based video on-demand (AVOD) has its appeal.

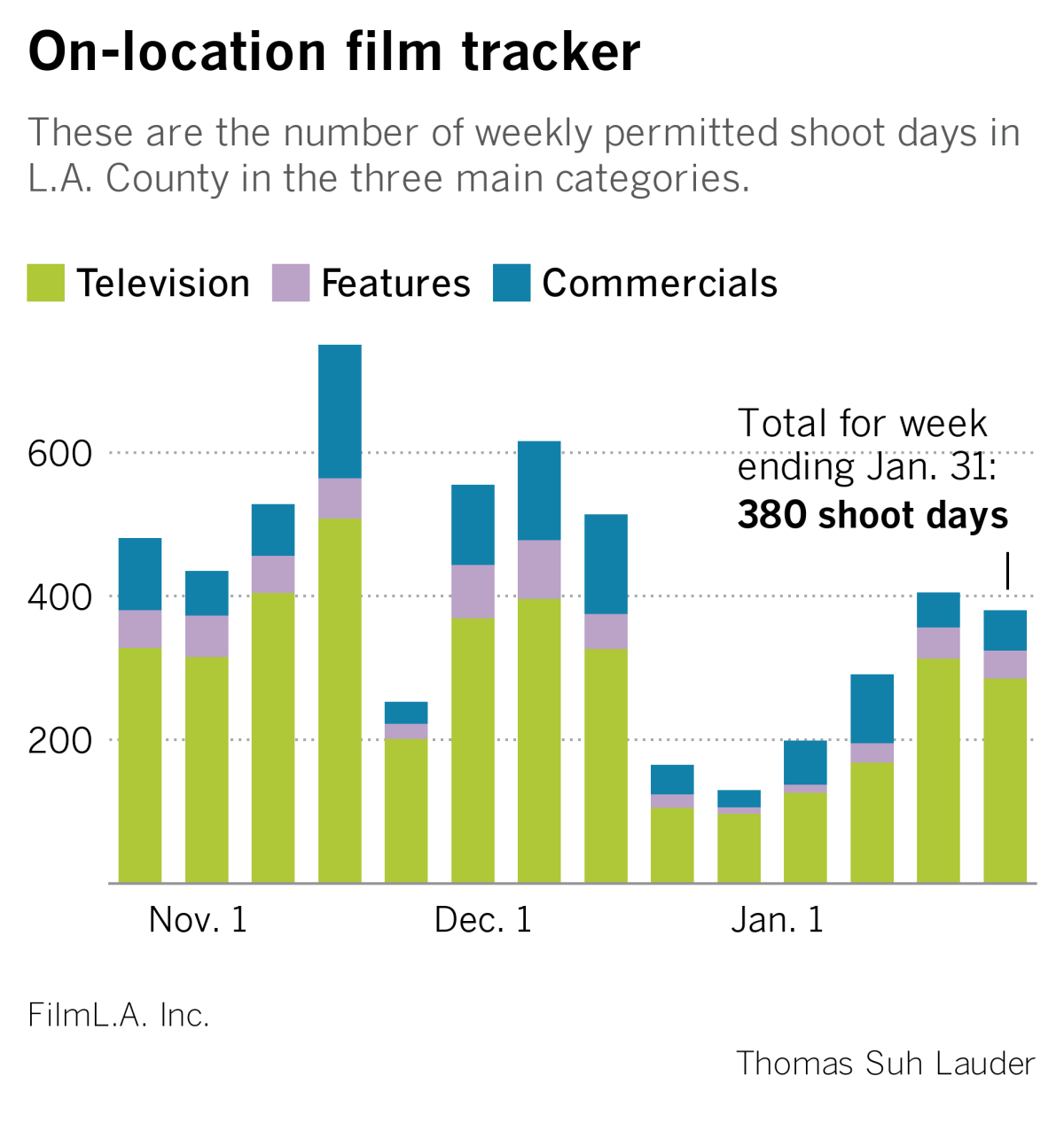

L.A. production

A new feature for The Wide Shot! Weekly production numbers for the Los Angeles area will be an exclusive, recurring part of this newsletter, courtesy of FilmL.A. Shooting days dipped in the last week after several weeks of gains, following L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer’s request for a pause to continue until the end of January. Last year, production in the L.A. region hit a 25-year low.

Did ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ ‘work?’

AT&T has to be encouraged by HBO Max hitting 17.2 million activations, double what it had in September. Some of that is due to “Wonder Woman 1984” launching on the service on Christmas, so we’ll have to wait and see how many people stick around and how many more sign up for Warner Bros.’ upcoming slate.

WarnerMedia’s direct-to-consumer executive Andy Forssell on Sunday said “The Little Things,” starring Denzel Washington, “immediately shot up to number one” on HBO Max after debuting simultaneously in theaters (real numbers M.I.A.). “Judas and the Black Messiah” should attract some interest after its Sundance premiere, adding to the service’s cachet with cinephiles.

But AT&T has problems well beyond growing HBO Max, as evidenced by its $15.5-billion write-down in the quarter thanks to the ongoing DirecTV debacle. To summarize MoffettNathanson‘s assessment, the Dallas phone giant is stuck between Wall Street’s desire to see growth at the company and its demand for AT&T’s dividend.

“If AT&T had the luxury of a strong balance sheet, investing for long-term growth would be an easier call,” the analysts wrote. “They don’t.”

Sundance shines for some

Supply and demand. Going into Sundance, agents predicted that the relative scarcity of available films and the increasing need for streamers to buy content would create a hot market for high-profile titles. In at least one case so far, that was right on the money. Apple over the weekend paid a record $25 million for the rights to Siân Heder‘s “CODA” (short for child of deaf adults), topping the benchmark Hulu and Neon set with “Palm Springs” last year.

‘Stonks’ never sleep

If Gordon Gekko were around, would he be one of the talking heads complaining about Reddit day-traders eating his lunch on CNBC? Or would he be kind of impressed by the meme-generating mischief-makers at r/WallStreetBets?

There are so many unknowns about the GameStop and AMC stock frenzy. I wrote last week about the impact on AMC Theatres, which was able to capitalize on the stock popping earlier in the week, though it missed out on the bigger surge on Wednesday. I still wonder how much of the trading is really being done by the people posting rocket ship emojis on social media. For what it’s worth, AMC’s shares closed virtually flat Monday at $13.30.

Where does this go from here? It seems safe to predict that folks who bought GameStop at more than $400 stand to lose money. But the traders turning the stock market into “Borat”-level prank comedy don’t seem concerned, as they share gleeful memes about “stonks,” “taking “$GME to the moon!” and “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” For further reading, check out Times game critic Todd Martens’ take on the GameStop traders’ overlap with online fan culture and Michael Hiltzik’s column drawing parallels with earlier market manias.

More top stories

—Did “Peak TV” actually peak? From THR: “According to data supplied annually by Disney-owned FX, the total number of scripted original series on broadcast, cable and streaming outlets totaled 493 in 2020.”

—Promising update on the production front: “Commercials shoots, a key driver of local production, are set to resume on the streets of Los Angeles,” writes Anousha Sakoui, as the county begins to ease its COVID-19 restrictions. “SAG-AFTRA, the Producers Guild of America and a bargaining group that represents commercial advertisers and advertising agencies agreed to lift a recommended halt to such productions.”

—Authors aren’t happy with Simon & Schuster’s proposed merger with Penguin Random House, Dorany Pineda reports.

—Stephen Battaglio‘s obit on Jamie Tarses, the first female network entertainment head, who died Monday at 56.

—New social media unicorn Clubhouse: where tech moguls and hip-hop stars alike promote their thought-leader brands. Who stands to gain? asks August Brown.

—Kids are king in Hollywood, and not just when they toddle their way onto the air during the local weather report. Variety delves into the media companies’ battle for dominance in children’s programming.

On the calendar

Sundance Film Festival Awards are tonight, with winners set to screen Wednesday, the final day.

Golden Globe nominations will be announced Wednesday, and it’ll probably be another good morning for Netflix and other streamers.

SAG noms are coming Thursday.

Finally... the ‘bitter’ end

What I miss most from the Before Times — other than just seeing people — is live comedy. Of the recorded specials I watched last year, Eddie Pepitone‘s ironically named “For the Masses,” released over the summer on Amazon Prime, came the closest to capturing the energy of an in-person set. The surreal rants from the Brooklyn comic, billed as comedy’s “Bitter Buddha,” are certainly not for everyone. Think of a less-sunny Lewis Black. But his big closing bit, in which the consumerism-skewering absurdist recreates an audition for a Downy detergent commercial that goes way off the rails, is one of the best-constructed routines I’ve seen in a long time.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.