Lacking perspective? Try orbiting the Earth at 17,500 miles per hour

- Share via

Review

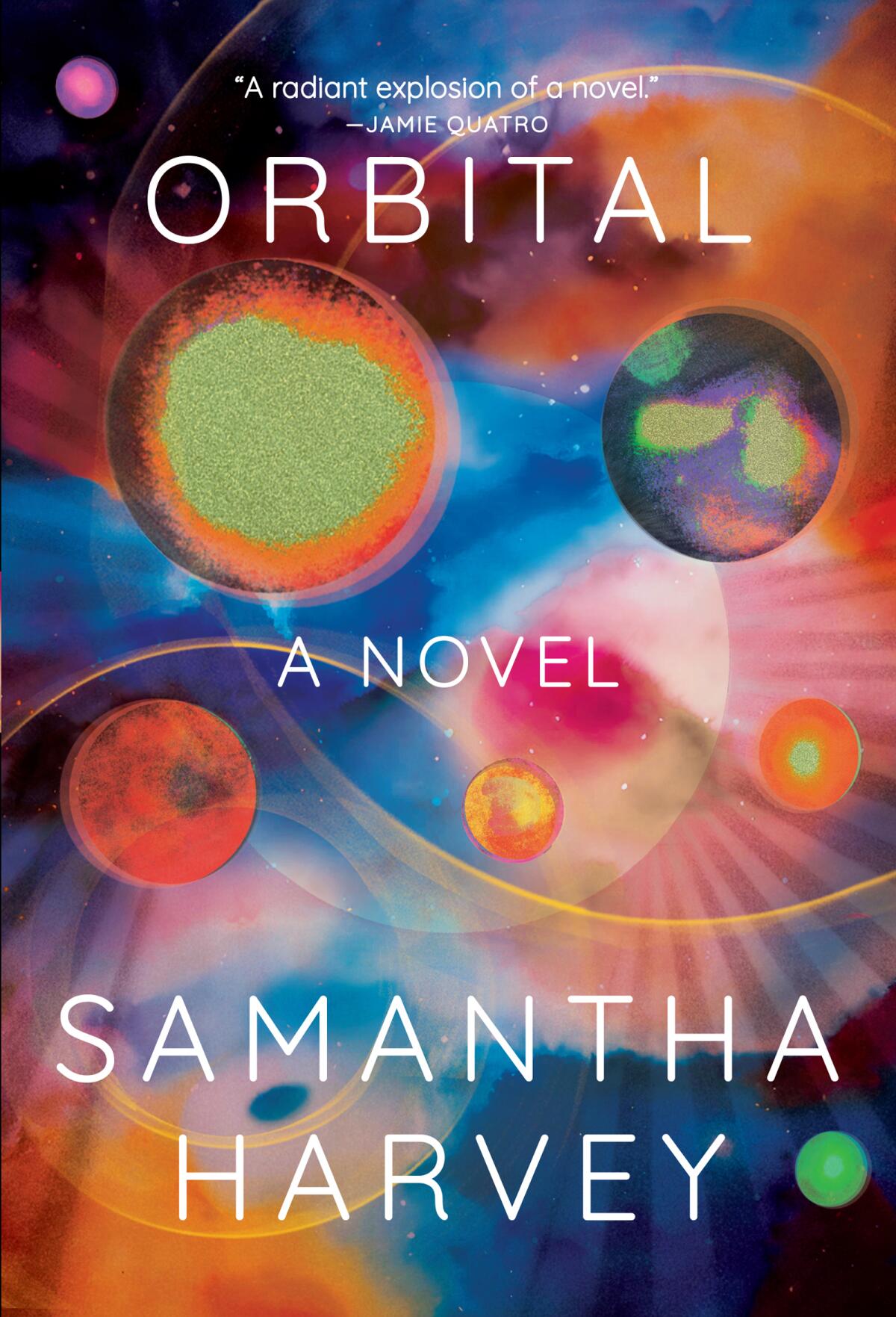

Orbital

By Samantha Harvey

Atlantic Monthly: 193 pages, $24

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Buzz Aldrin, the second astronaut to walk on the moon, admitted that after the 1969 Apollo 11 landing, he suffered from depression and alcohol addiction. “[E]motionally I felt like a mess of tangled-up wires inside,” he wrote in “Magnificent Desolation,” his 2009 memoir. Who would not suffer some kind of existential crisis after seeing the planet on which we live from such a mind-boggling perspective?

In 2023, most of us are also trying to see the planet whole — and pondering its survival. Climate change, armed conflicts and immense resource disparities threaten disasters that could affect the lives of millions. How should we look at the Earth? How do our lives affect the way we look, and what will really looking do to us?

Samantha Harvey’s fifth novel, “Orbital,” follows Aldrin’s footsteps into outer space, where six astronauts from various countries — two women and four men — inhabit a space station 250 miles above the Earth that circles the planet at 17,500 miles per hour, 16 times each day. Morning arrives every 90 minutes, “the sun up-down up-down like a mechanical toy.”

Three contributing critics pick their best fiction of the year, including work by Victor LaValle, Ed Park, Lauren Groff, Yiyun Li and Tania James.

These people aren’t just staring out the windows all day. They each have tasks to do, from personal care and fitness to scientific experiments and station upkeep. Each chapter covers a single orbit, and in moving from person to person, Harvey conducts a sort of Greek chorus, commenting on bits of specific geography and forgivably flirting with a few “big blue marble”-style clichés.

Sections about the mundane rounds serve to lull readers, as if we ourselves were gliding through space: “Outside the earth reels away in a mass of moonglow, peeling backward as they forge towards its edgeless edge; the tufts of cloud across the Pacific brighten the nocturnal ocean to cobalt.” Yet even as crew members go through their motions, the world intrudes.

Chie learns that her mother has died back in Japan. Shaun argues with Neil about the existence of God. One of the Russians, Anton, has a worrisome lump on his neck. Soaring above humanity, it seems, only heightens an individual’s humanity, even if it’s felt in the distance from others.

Harvey’s purpose, as a novelist, isn’t to teach the science of space travel. She does provide intricate detail about, for instance, how the station’s drinking water gets recycled from everyone’s urine, or how “the wide-awake, always-awake station vibrates with fans and filters.” Yet these elaborations — note the words “recycled” and “always-awake” — have less to do with the machinery of the station than they do with the orbiting minds of the humans on board.

Several of Harvey’s previous works have focused at length on a single person’s perspective. “The Wilderness” (2009) followed a character’s descent into Alzheimer’s. “Dear Thief” (2014) is an epistolary bomb about a woman’s anger at the best friend who stole her lover, and 2018’s “The Western Wind” swept into medieval England for a backward murder mystery that reads like a mashup of Dorothy L. Sayers, Graham Greene and Martin Amis. Perhaps it was the pandemic that pushed Harvey to the shorter, more intense bursts of “Orbital,” in which individuals live in such close proximity to their colleagues that thoughts are their only privacy.

Kate Christensen, whose latest novel is ‘Welcome Home, Stranger’ has always infused her writing with two things: food and the changes in her own busy life.

All literature deals with the tension between general and specific, public and private, individual and collective. Yet Harvey manages, in taking readers along to the final frontier, to remind us less of our essential loneliness and more of our mutual dependence. In an odd moment of narrative projection, a photo of the first space-station inhabitant in the cosmonauts’ cabin seems to think: “Humankind is not this nation or that, it is all together, always together come what may.”

Humanity, of course, has its blind spots. In each chapter, each orbit, there is always a part of the Earth’s magnificence that some or all of the crew miss — the Himalayas, Gran Canaria, the Tunisian salt flats. In that sense, these six people are akin to the 8 billion members of their species left behind; none of us could ever possibly take it all in.

If we can’t ever grasp the enormity, then “what use are words?” asks Harvey in Orbit 7. She’s channeling the six on board — how easily irritated they are by news, which invariably seems so petty from their current perspective. But even so, she is showing how words connect the earthbound to the consciousness of the explorers — even if those words are thought in different languages.

Harvey has said in an interview that she considers “Orbital” to be “a kind of space pastoral,” perhaps meaning that from up above we can better attain peace, harmony and a true appreciation of the magnitude of the universe. But her careful, musical diction makes a case that this is really a novel about communication both within and beyond words. She even tells us so in the book’s opening line: “Rotating about the earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies, at times convene.”

Bethanne Patrick recommends 10 new books to get you through the end of 2023, including dystopias, a quirky travelogue and an uncommonly exciting math primer.

So much for privacy! That may be the author’s point, and it might help us understand what drove Aldrin to drink and depression. Once we’ve seen the magnificence and the desolation, it’s tough to return home and rejoin the Earth’s squabbles, whose life-or-death stakes only highlight their absurdity. And yet, this is life as we know it. Without news from home, “Orbital” might well have been more of a tone poem than fully realized fiction.

Instead, even at under 200 pages, “Orbital” is a complete novel, all the way to its conclusion. With a few tiny strokes of foreshadowing and a few lovely paragraphs of description, Harvey manages to bring readers back down to Earth, astounded that they’ve traveled so far in such a short period of time, having finished their own orbit through the realms of her rich imagination.

Patrick is a freelance critic, podcaster and author of the memoir “Life B.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.