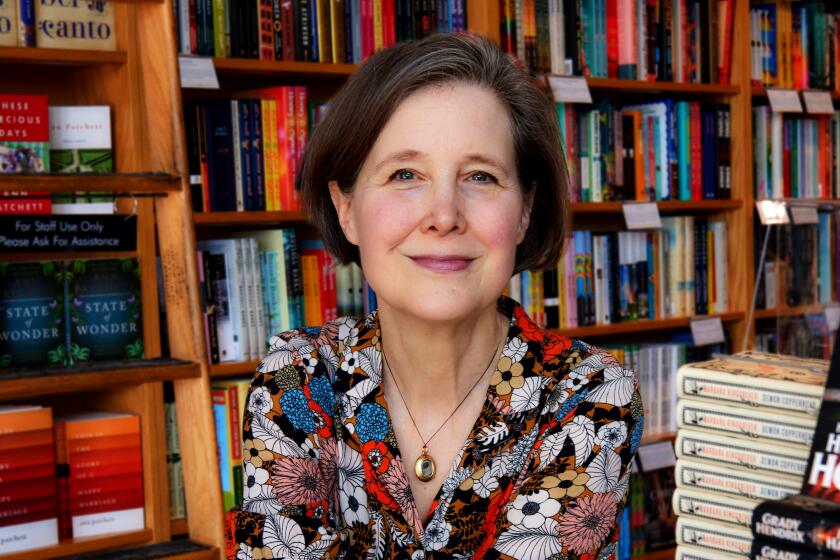

‘I don’t know a character until I know how they eat’: Kate Christensen’s delicious plots

- Share via

On the Shelf

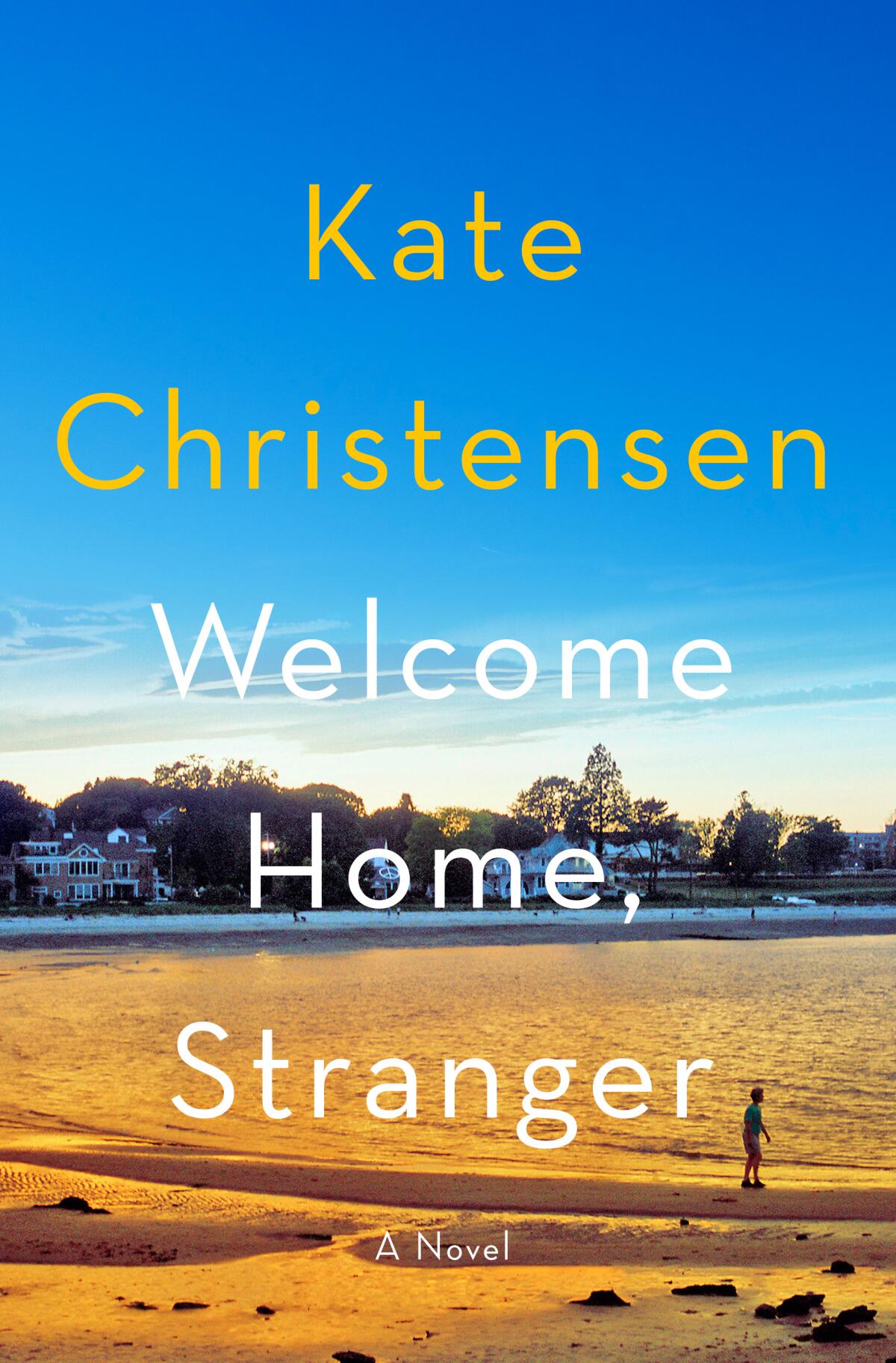

Welcome Home, Stranger

By Kate Christensen

Harper: 224 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There are a few reasons the novelist Kate Christensen, speaking via video chat from her home in Taos, N.M., is discussing the best lobster rolls in Maine.

The first is that the buttery sandwich figures in her new novel, her eighth, “Welcome Home, Stranger.” Rachel, a science journalist in Washington, D.C., has made a pilgrimage back to Portland, where her mother has died and left her a two-bedroom condominium. In the course of a plot woven out of multiple meals — pizza scarfed down while painting cabinets, “spring carrot and golden lentil” soup at a bougie restaurant, lard-fried corned beef and onions up in the North Woods — there is the moment Rachel convinces her ornery sister Celeste to drive to Two Lights State Park for a lobster roll worth the trip.

For the record, “Two Lights isn’t my favorite lobster roll in Maine,” says Christensen. “That would be Bite Into Maine, a food truck in Fort Williams Park.” (Also, try the haddock sandwich at Young’s Lobster Pound in Belfast.)

Food is essential to Christensen’s writing — always has been. The first memoir of her itinerant and complicated life is titled “Blue Plate Special: An Autobiography of My Appetites,” followed by a memoir-cookbook called “How to Cook a Moose,” a clear homage to M.F.K. Fisher’s classic “How to Cook a Wolf.” Two of her most memorable novels-as-character-studies are “In the Drink” and “The Epicure’s Lament.”

Sigrid Nunez’s new novel, ‘The Vulnerables,’ completes a trilogy that began with ‘The Friend,’ which won a National Book Award. What’s her secret? Odd pets.

“I don’t know a character until I know how they eat in public, what they cook, what they would serve a guest, and what they eat when they’re alone,” Christensen says. “It’s all part of who we are. And I feel really unpretentious about food. Every single food moment in this novel says something about Rachel as a character, and her very real homecoming.”

For example, Rachel can’t eat what Celeste makes, supposedly because of the toxins, but after the sisters travel to a camp in the woods where her mother’s siblings live, and their Aunt Jean Gautreau cooks up a feast full of saturated fat, Rachel digs in with abandon. “I did that very deliberately,” Christensen says, “so that whatever she’s eating or cooking or thinking about in terms of food is right where she is in changing.”

Those dishes reflect the worlds Rachel is moving through as well. “Food is class,” says Christensen. “What people eat says so much about their socioeconomic status, in addition to their tastes. … For me, food is always a way into character.”

Another reason for that lobster-roll digression: Christensen’s nostalgia for Maine, and her habit of infusing her work with a deep knowledge of place even as she herself has lived a wandering life: Born in Berkeley, raised in Arizona, college in Oregon and graduate school in Iowa followed by New York City, New Hampshire, Maine and, finally, hippie-chic and sun-soaked Taos.

In Christensen’s work, those wanderings translate to settings that dig deep beneath postcard surfaces — including the family campground presided over by Aunt Jean. “Maine has hardscrabble communities, many of them in the almost oppressive woodland of the interior,” the author says. “It’s not all open vistas of the seas and shingled cottages of the rich. It’s cold, hard, long winters, people having bean suppers at church, traditions that go back to the 1600s.”

Headed for the holidays, we round up 6 gift-able mystery novels and ask their authors — from Lee Goldberg to Tess Gerritsen — three things we’re dying to know.

From early novels like “Jeremy Thrane” to her PEN/Faulkner Award-winning “The Great Man,” Christensen’s inspirations all come out of her own struggles, including a divorce and a fraught relationship with alcohol. Five years sober, Christensen now mixes up pitchers of mocktails: “I call them ‘foxtails,’ and it’s wonderful.” Rachel, too, is trying to stay away from the drink, with less success.

“There’s always a question at the center of a novel that is one I’m grappling with, and my first-person narrators are often avatars in a way, or alter egos,” she says. “They have qualities in myself that are latent, that I haven’t actually realized. It’s a way of living in another person’s life that I invent, hypothetically casting myself into various situations that address stuff I’m engaged with in my own life.”

In the case of “Welcome Home, Stranger,” there is grief and homecoming, of course, but the most personal element is that Rachel, at 53, is going through menopause — something Christensen has experienced and that women, including novelists, rarely discuss.

“I feel like nobody talks about the upside of menopause!” Christensen exclaims. “It was like going through adolescence in reverse, when I sort of had no control over my body, my unpredictable moods, my brain fog. But I came out at the other end of this wind-tunnel roller-coaster ride with my brain clear. My memory came back. I could sleep again. It was a pleasant shock.”

Rachel — despite her challenges with Celeste, her old lover David, her ailing ex-husband and her enervating work life — also discovers good things about her new life as her body changes. “She realizes she’s become invisible,” says Christensen. “Women in menopause … what we’re really about to become are elders. There’s a lot of loss, and a lot of reckoning.”

Ann Patchett’s ninth novel, ‘Tom Lake,’ distills the soul of her work and her life — her welcoming bookstore, her fear of distractions and her lack of regrets.

Fans of Christensen might notice a change of tone as well. “A lot of my first-person narrators have been people who make their own trouble and shoot themselves in the foot, and there’s comic energy generated from all that,” she says. “But this is, to me, a more serious novel. It’s an existential novel ultimately about the Trump years, written in lockdown and finished during the early part of the Biden administration. I wanted to show a woman dealing with a lot more stuff than I was. She’s alone in the world. She’s losing her ex-husband to ALS. Her sister is a bitch. What will come next for her?”

Christensen has already moved on to what’s next: she and her husband moved to the Southwest to be closer to aging family members. The couple had cherished their “old, beautiful, 1900s brick house” and “never wanted to leave Maine. I never wanted to sell that house. … The community I found there, the feeling of home I had, well, I cried as we drove away behind the U-Haul — so hard that I could hardly see the road.”

Ultimately, though, “I am adaptable, and I think learning to land on my feet is something I got from my mother. It’s one of the life skills she instilled in me and my sisters, that home isn’t necessarily a permanent place.”

Without giving anything away, Christensen notes the parallels with Rachel’s plight. “This is a novel about stripping everything away from someone. It took draft after draft, because at first I didn’t have the heart to put Rachel through what I knew I had to put her through for the book to work.” If, for Christensen, all protagonists are alter egos, at least you know that, like her, they have the strength to endure the trials their creator has sent their way — along with very good taste in food.

Patrick is a freelance critic, podcaster and author of the memoir “Life B.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.