- Share via

On the Shelf

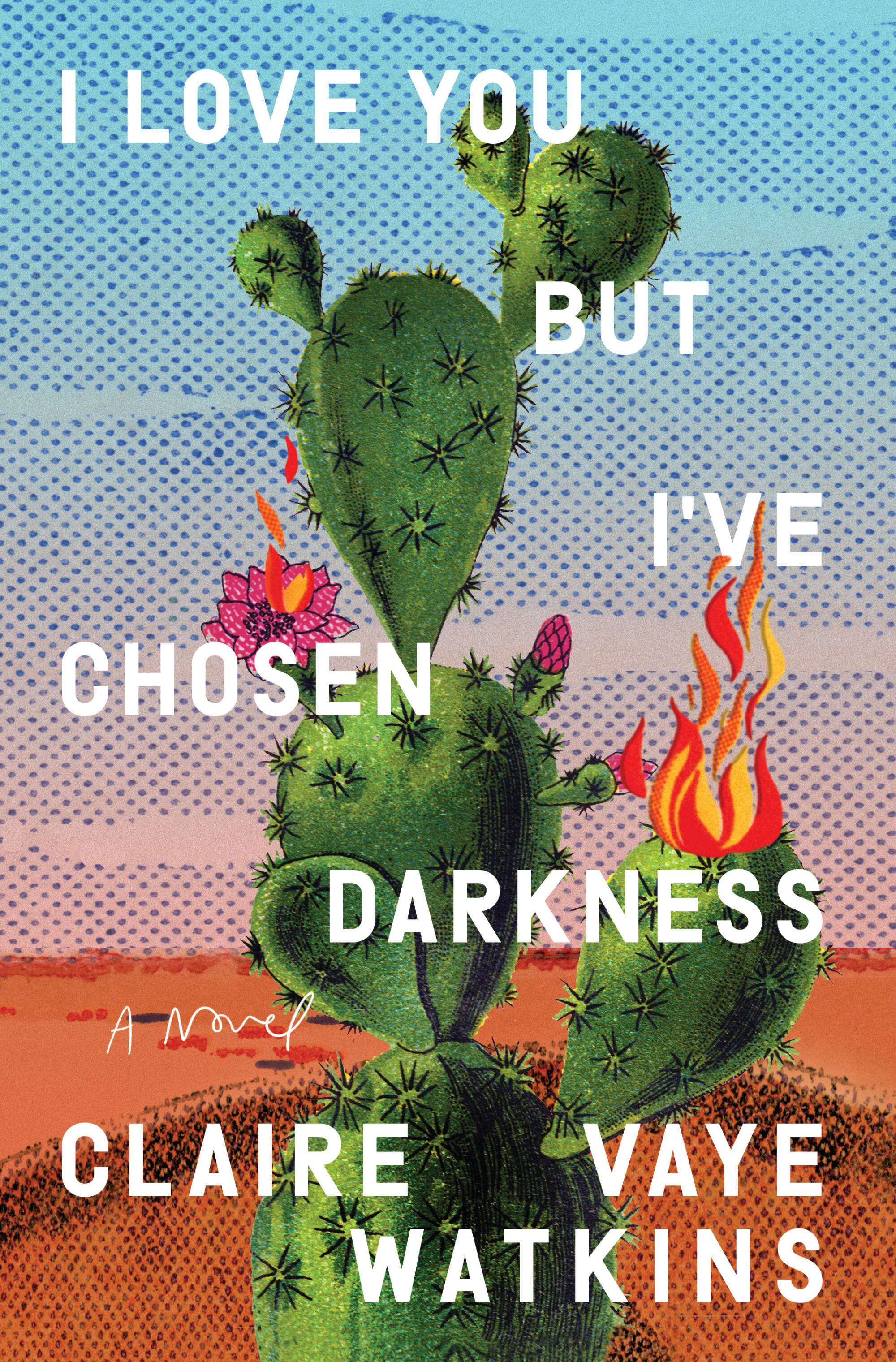

I Love You but I've Chosen Darkness

By Claire Vaye Watkins

Riverhead: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

My low-slung rental car sways down a sand road before pulling up to the tidy, metal-seamed house in Twentynine Palms that author Claire Vaye Watkins has called home for the last year. Everywhere, creosote. Glaring rock. Sunlight that leaves sparks inside your eyelids. Surrounding the house are three illegal pot farms. The view out front is an expanse of shining rooftops making up the largest Marine base in the country, complete with a faux Afghan village for raid training. Distant booms signal live rounds pitting the mountains. The house often shakes. “California,” Watkins once wrote, “the failed experiment.”

She returned to her native Mojave in part to finish her new, pseudo-autobiographical novel, “I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness.” It’s a beautifully arranged tackle box of everything Watkins does best — cut-through-the-bone narrative of family apocalypses; custom blending of the historical, the unimaginable and the impossible; enchanting, terrifying encounters with the American West. “The music of that place is the music of her language,” says novelist Karen Russell, a decade-long friend.

Watkins had sent me a list of essentials for my visit: a wide-brimmed hat, lip balm, days’ worth of water, a healthy fear of the desert. “I know you’re terrified — good! One must approach the desert with humility and vulnerability,” she wrote. “Plus it is maybe the hottest possible time to visit.” It was signed, “devil and darkness!”

Depending on whether you think the desert will restore you or shrivel you dry, Twentynine Palms, beyond Joshua Tree’s “Silver Lake West” decor shops and not quite out in the true Mojave, is either the last tether to civilization or the first step toward freedom.

“This is like a suburb to the Mojave I grew up in,” says Watkins; her hometown of Tecopa, Calif., population 150, is three hours north.

Before Twentynine Palms, “I had burned my life out from the middle, like a canoe.” A year in Portland, Ore. Another year split between Austin, Texas, and Las Vegas, where she was a fellow at the Black Mountain Institute, with a spell in New Mexico in between. Ann Arbor, Mich., for “many years ... three years.” Princeton. Bucknell. Ohio State for grad school.

Also: a left-behind marriage, a discarded tenure-track job, a redefined relationship with her baby daughter. When she left Ann Arbor, she decided, “I’m just going to clear the deck. I don’t know what I do want to do in this life, but I know what I don’t want to do, and I’m going to start by stopping doing everything I don’t want to do anymore.”

Ecologist Jim Cornett is as fascinated with California’s driest places as ever. But the signs of stress brought on by climate change terrify him.

All the while, her reputation grew as the new literary savant of the American West. Editor John Freeman, then at Granta, met Watkins at a conference in 2009 and asked her for 900 words on the topic of “family.” He calls it “one of the happiest beginnings of any editorial relationship.” Watkins sent him a brief memory of walking Death Valley with her father, once Charles Manson’s “right-hand man,” and bowled him over with what he calls “her ability to stare in the face of publicized memories and wrest them back.” She sold a short story collection, “Battleborn,” at age 26 but turned down any two-book deals.

It’s “poor kid s—,” she says, “if you’ve had enough houses foreclosed on, you don’t want to owe anyone anything.” It worked out. “Battleborn” earned her the Story Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize, a Guggenheim grant and a berth on the National Book Awards’ “5 Under 35” list. Her first novel, “Gold Fame Citrus” — which should be considered the novel of the climate disaster — confirmed her as a writer whose genius is big enough to wrestle with a collapsing planet. To finish each book, she returned to the Mojave, seeking not comfort but reality. “The West is a lot harder to love up close.”

So she’s a homeowner now. The house was originally built under California’s Small Tract Act — you‘d get 5 acres, but you have to improve the property within a year. “The 20th century’s Homestead Act,” she says with a laugh, “because that went so well.” It isn’t meant for permanent occupation but Watkins is settled, tenured at UC Irvine, living with her boyfriend, Michael, whom she met at Black Mountain. Her daughter, Esmé, 7, comes for the summer and spends the school year on the East Coast with Watkins’ ex, novelist Derek Palacio. “Esmé” is tattooed across Watkins’ knuckles in childish print. Impossible to write, wash, work without seeing her name.

For the record:

11:56 a.m. Sept. 30, 2021An earlier version of this article stated that Claire Vaye Watkins bought her home through the Small Tract Act. The house was originally built as part of the now-lapsed act. Watkins was not a student when she flew a banner over a Michigan-Ohio State game and did not receive a Carnegie medal. The towns of Tecopa and Shoshone are in California, not Nevada.

Watkins says she spends most of her day outside in the hammock, watching the desert “put on the show.” A wood rat she can’t bring herself to kill has recently taken up residence under her house, and every day it leaves piles of rocks by her desk window as an inscrutable offering. Her own rocks and gems — turquoise her father mined, stones from a shop her mother ran in Shoshone, Calif. — are right above that pile, on the windowsill. The desert gives and takes.

A toppled pile of books next to her desk, right under that window:

“Ill Nature: Rants and Reflections on Humanity and Other Animals” by Joy Williams

“Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water” by Marc Reiser

“The White Album” by Joan Didion

“This Land: How Cowboys, Capitalism, and Corruption Are Ruining the American West” by Christopher Ketcham

“Let Me Tell You What I Mean,” a new collection of old essays, offer a chance to reassess the writer’s politics and privilege.

Off in the distance, a column of gray rain falls. “They’re getting some weather over in Landers,” Watkins notes with a little surprise. The clouds stretch and loop, the most mutable thing out there. We wait for a visit from Bernie, her pot dealer, and then climb into her Prius, its interior dappled with mud from a flash flood. She says Esmé implored her to clean it, “but that just isn’t how people out here live.” We head out.

“I love you but I’ve chosen darkness.” (period included) was tattooed across the chest of Claire’s dead boyfriend, Jesse. Jesse is a character in her novel of the same name, and he was “very real,” though such things don’t necessarily matter for the purposes of her fiction. Claire, the novel’s protagonist, is absolutely Watkins and also a fabrication. “You’re going to assume that’s me anyway, so I’ll just make it me,” she says. The novel is fiercely committed to destroying the idea that personal mythology can be only true or false.

We’re eating at the Joshua Tree Saloon, its parking lot full of strikingly clean mockups of an Old West town. Hokey tourist stuff, but delicious fish tacos. She wanted, she explains, to “circumvent the speculation of an autobiographical novel, saying, ‘Yes, it really happened,’ and then put things in there that couldn’t possibly happen.”

Like Watkins’ earlier work, “Darkness” is a collage of forms, what she calls “pack rat fiction.” The first chapter is a postnatal depression questionnaire filled out with discursive irony. Letters written in the early 1970s by Claire’s mother, Martha, are allotted throughout, in reverse chronological order. The novel’s backbone is the story of Claire heading to Reno for a book event and taking nearly a year to get high and screw around and dip in hot springs and drop in on her grandma and shack up with two women in a junk-box cabin before she reunites with her husband and daughter, only to swear off convention for good. The scenery out the window is her childhood.

Watkins (and Claire — the distinction for her, and us, is purposely vague) was born in 1984 in Death Valley. Her sister, Lise, one year younger, was really born in Death Valley — on the side of the road in an un-air-conditioned Mazda in August, on a five-hour drive to the closest hospital that would accept Medi-Cal. That year between them would make a world of difference: Claire was able to go to college; Lise wasn’t. Claire skedaddled to L.A. when their mother’s Oxycontin addiction veered into dangerous terrain; Lise stayed behind with their younger sibling, hosting interventions. (“Medicine tossed her to the Sacklers and they sucked her dry, destroyed her and everyone around her, and blamed her for it,” Watkins writes.)

Originally, “Darkness” was meant for Claire’s siblings. She thought she’d make three or four copies and see if their memories matched up with her own. Then, it was a Shakespearean comedy of errors — “when I thought my marriage was going to last.” Later, when she realized monogamy was a trap, she took it more seriously as a publishable project. But, she says, “I had to finish that part of my life before I could write it.”

Patrick Radden Keefe’s much-anticipated “Empire of Pain” lays it all bare

Watkins has always been telling the story of herself. She wrote “Ghosts, Cowboys,” the first story in “Battleborn,” while an undergrad at the University of Nevada, Reno. It’s a history of the “beginning” of Nevada that starts over and over — with the leak of the Comstock Lode, her mother’s toddler memories of nuclear explosions and her father’s orgies with the Manson Family. Freeman remembers that once, at a literary event in Minneapolis, he questioned her a bit too deeply about it all. She responded, without animosity, “Have I polished my pain well enough for you?” Nonetheless, she picks it back up in “Darkness.”

“I’m unapologetically regional,” Watkins says. “It’s OK to just circle the same territory. Even a shrinking territory. Pretty soon, I’ll just write about one rock.” She sees her own words as emerging directly from her parents’. Which is why their voices — her mother’s letters, honed into a shared voice; passages from her father’s 1979 memoir, “My Life With Charles Manson” — settle so naturally into her own switchback prose.

After Paul died of cancer when she was 6 (a nuclear-test “downwinder,” Watkins notes), her mother rarely talked about his notorious past — not out of shame (“Sweetheart, he was Charles Manson’s number one procurer of young girls,” she says in “Darkness” when asked if they’ll see each other in heaven), but out of grief. Claire has his memoir by her desk; she can’t remember the origins of this particular mangled copy. It may have been her mother’s.

Martha had rehabbed in Claire’s infancy — long enough for her grade-school daughter to play sports and have health insurance. Martha also kept a dead rattlesnake in the freezer (she never found the time to taxidermy it) and lassoed her kids into helping her pull off small cons (ripping off the homeowners’ insurance, stealing plants under cover of night). She relapsed later, when a Lyme diagnosis led to a prescription for Oxycontin and a cycle of overdoses leading to her death when Claire was 22. American greed took both her father and mother. “Darkness” makes them hers again.

Still, regret isn’t one of her primary modes. Claire calls herself a banshee, a dirt bag. She rushes into contradiction. As Russell puts it, her friend has “a radical freedom in the way that she’ll follow the gleam of her own mind” — in writing and in life. She will mock California’s woo-woo atmospherics, how it “makes you so chill, maaaaaaan,” in a surfer drawl. And then she will spend the afternoon offering quotes from “A Course in Miracles,” a “divinely received” text by Columbia professor Helen Schucman. She’s reading it for her book club. “Is this a cult? Yeah, I think, but it’s my kinda cult.” Worrying over consistency wouldn’t occur to her.

Reading list: Here’s a guide to the still-growing library of true-crime books that try to make sense of Charles Manson, his followers and their killing spree in summer 1969.

I ask how she’ll feel if Esmé reads “Darkness” someday, given that it kick-starts when Claire leaves her daughter for a year. “I’m a kid who read about my dad being in Helter Skelter,” Watkins says, then laughs and yelps, “and I’m fine!” But really, she says, “I’m so glad he figured out how to put it all down. … We don’t really get access to our parents as people.” Anyway, he got to have a second act. And so does she.

Before getting up to leave the saloon, we gaze through the window at the menacing storm clouds, ever encroaching. Claire is pumped: “It’s doing this for you,” she crows.

We talk about Watkins’ so-called second act as we leave the town of Joshua Tree and drive past Kim Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead, a tiny cabin erected in homage to the settlers of yore and the homesteaders of 2021. Then there are artist Andrea Zittel’s sleeping pods arrayed on the desert hillside, each just a bed with a roof like a trunk, designed to house artists and question self-sufficiency. Claire’s project is her own, but she isn’t alone out here. And she’s worked off the page as well. She once hired a plane to fly over the Michigan-Ohio State game with a banner reading, “Stop Rape.” In the lead-up to the 2020 election, she collaborated with multimedia artist Brent Holmes to erect a billboard in Las Vegas for a hotline: “Make a List of Everything You Have Lost.” Thousands called in.

The storm hit her homestead while we were away; the sand road is suddenly a river. It’s hard to know, she tells me, which eddies you can cruise through and which will send you skidding. (We cruise through.) The power has gone out at her house; the heat is growing brutal. But when we head out for a sunset hike in the national park, the showers have already turned the trail into a microclimate super bloom. Claire lightly touches the leaves of every plant she passes and yells out their names while smoking a rapid succession of joints.

On her and Michael’s special sitting rock, the three of us talk books and watch the mountains go purple. Ben Lerner, Thomas McGuane, Joy Williams and Jenny Offill come up. Claire is blissed out, her hands dusty. She just read Claire-Louise Bennett’s forthcoming novel, the first she’s enjoyed in a while. She values “A turn back on yourself. A self-implication … An immediacy, close to the bone, like this cost the person a lot to write, and they put on the highest spit shine, but they don’t lose any of the rawness of the discovery, of the surprise.”

That is, not coincidentally, what Watkins does, as the most riveting voice of the unsalvageable West. And, more than ever, in the West. “I do have a strong desire to feel rooted,” she says. “I don’t want to be writing about the West from far away anymore. And I didn’t want to write about it in an elegiac or nostalgic mode.” Instead, her fiction knows that paeans are lovely, useless things. The West needs to come alive in fiction, but also to die. It needs to make humans hurt the way humans have hurt it.

We trip our way back to her car in the near dark. Eventually, Claire flips on a headlamp, though it helps only a little. Earlier in the day, before we set out in the fast-changing desert, I asked: “Do you want to live in a mystery?” She responded without thinking: “Of course! I think it’s a miracle to be open and going toward something you don’t understand.”

Cline’s new collection of short stories, her followup to “The Girls,” features women performing their sexuality and older men in cancellation limbo.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.