Paul Auster’s new novel lacks his usual postmodern fireworks. Thank God for that

- Share via

Review

Baumgartner

By Paul Auster

Atlantic Monthly: 208 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

On Jan. 10, 2009, Paul Auster wrote a letter to his friend and fellow novelist J.M. Coetzee in which he singled out several convenient coincidences in Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.” He argued that these “plot manipulations” were ludicrously implausible but creatively effective. “There are things that happen to us in the real world that resemble fiction,” he added. “And if fiction turns out to be real, then perhaps we have to rethink our definition of reality.”

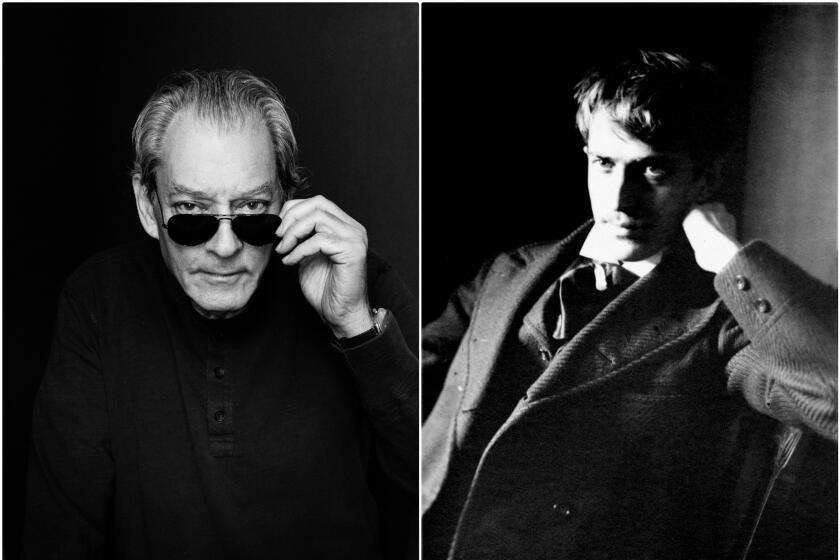

Over the course of his career, Auster has crafted fiction that purports to be real while challenging our definition of reality. Most notable are his breakthrough 1985 novel, “City of Glass,” which combined hard-boiled detective fiction with existential inquiry and featured a character called Paul Auster; his 1994 fable, “Mr. Vertigo,” with its (quite literal) flights of fancy; and “Man in the Dark” (2008), whose dreamscapes conjured up parallel visions of modern-day America.

In “Burning Boy,” the novelist Paul Auster finds a kindred spirit in the short-lived late 19th century novelist — one he celebrates to a fault.

Certain themes and leitmotifs are constant presences in his playfully experimental fiction. Like Dostoevsky, Auster routinely serves up lucky occurrences and chance encounters. He explores contingency, identity and illusion and nests stories within stories. His mostly male protagonists share some of their creator’s traits but endure their own trials: They head out on fact-finding missions or go nowhere fast; they try in vain to forge their own destinies or, like Marco Stanley Fogg in 1989’s “Moon Palace,” are “utterly scorched by fate.”

A good Auster outing contains drama, mystery and trickery. A bad one puts us in mind of the description of the Florida sun in “Sunset Park” (2010): “It is all glitter and dazzle, but it offers no substance.”

“Baumgartner,” Auster’s latest novel — his 18th — contains some of his trademark tropes. And yet it couldn’t be more different from its predecessor. While the 2017 Booker Prize-shortlisted “4321” was a hulking, sprawling bildungsroman that charted one man’s four lives in long, meandering sentences, “Baumgartner” is a more scaled-down, stripped-back affair that traces a single life-trajectory in a more conventional way. And it is all the better for it.

The book opens with a series of accidents. Sy Baumgartner, a 70-year-old professor of philosophy at Princeton, scalds his hand at the stove. Shortly afterward, he learns that his cleaner’s husband has sliced off two fingers with his buzz saw. Then, as he escorts Ed Papadopoulos, a young meter reader, down to the basement, Baumgartner takes a tumble. While recovering from the fall and musing on “this day of endless mishaps,” his mind wanders back to 1968, replaying the moment in Manhattan when he first caught sight of Anna, the woman who would become the love of his life.

After a few years of virtual ceremonies, the 42nd Los Angeles Times Book Prizes was held in person Friday at USC, kicking off the Festival of Books.

Just when it seems the novel will develop into a tale about an unlikely friendship between Sy and Ed — the old academic and the new kid on the block — Auster has his hero disappear again down memory lane. Baumgartner recalls Anna’s unexpected death a decade ago — how in his grief he lost himself in her manuscripts before doing something useful and finding a publisher for a collection of her poems. He reminisces about his father, a Polish-born dress-shop owner, and his seamstress mother. And he remembers that pivotal day when he, an “unsuspecting Newark dirt-boy,” was informed of the scholarship that allowed him to break free of “this mean little nowhere.”

The novel is not solely composed of flashbacks. In the present, Baumgartner retires, meditates on his mortality and contemplates another shot at marriage with a colleague. Then a student in Michigan tells him she is doing her dissertation on Anna’s work and makes plans to visit, triggering irrational fears for her safe arrival and fresh recollections of his dearly departed.

“Baumgartner” shifts among a variety of tones. At the outset, there is tragicomedy in the hero’s blunders, his lively banter with Ed and his banal exchanges with UPS driver Molly. Later, we get a surreal dream sequence in which Baumgartner answers the disconnected phone in Anna’s study and listens to her voice from beyond the grave. There are poignant streaks throughout as Baumgartner delves into the past — or, rather, submerges himself in the “world of Then.” Auster adds more color to the proceedings by interspersing his narrative with samples of his characters’ autobiographical writings: Anna’s stories and Baumgartner’s account of his trip “through the bloodlands of Eastern Europe.”

Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee’s new novel, ‘The Pole,’ is the taut but clever story of a woman’s almost-affair — and the paragon of a great author’s late work.

The book is not without its faults. Sometimes Auster strains too hard to make his prose appear original; at other junctures he settles for hackneyed phrasings. For the most part, though, he succeeds in creating a captivating portrait of a man who has loved and lost and is preparing for his last stage of life. In contrast to Mr. Blank, the amnesiac protagonist of Auster’s “Travels in the Scriptorium” (2006), Baumgartner proves fascinating and endearing for having the ability to examine his own history — where he came from, what he has experienced and where he has ended up.

Some readers will rue the absence of reality-warping plot contrivances, unreliable narration and metafictional devices. But by dispensing with his postmodern pyrotechnics, Auster has produced a more grounded and consequently more believable work about a memorable life — and a life of memories. It may not be vintage Auster, but it is moving and compelling enough to qualify as a late-career triumph.

Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.