Review: Why is Paul Auster so obsessed with Stephen Crane? Find out in 800 pages

- Share via

On the Shelf

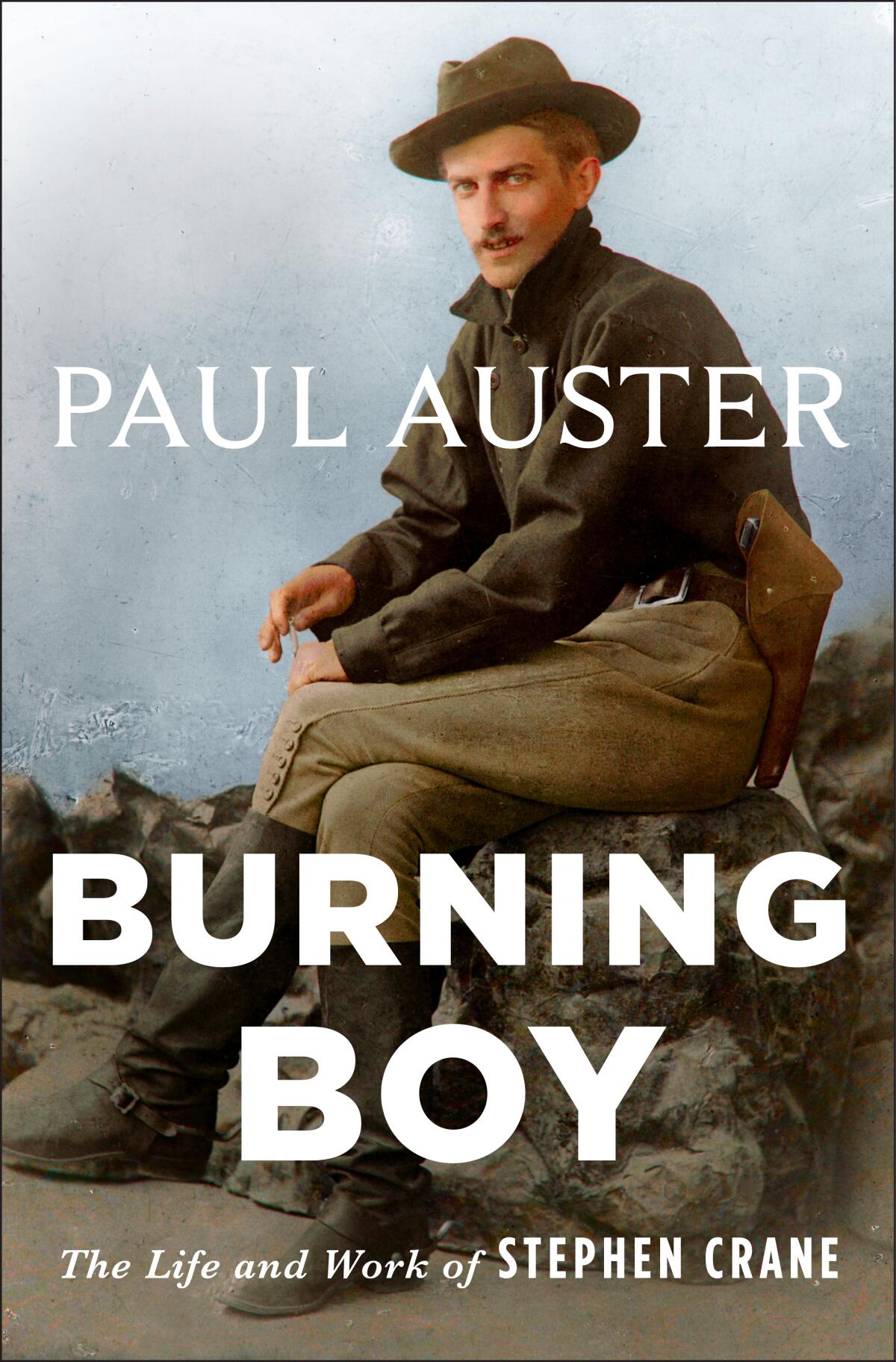

Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane

By Paul Auster

Henry Holt: 800 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

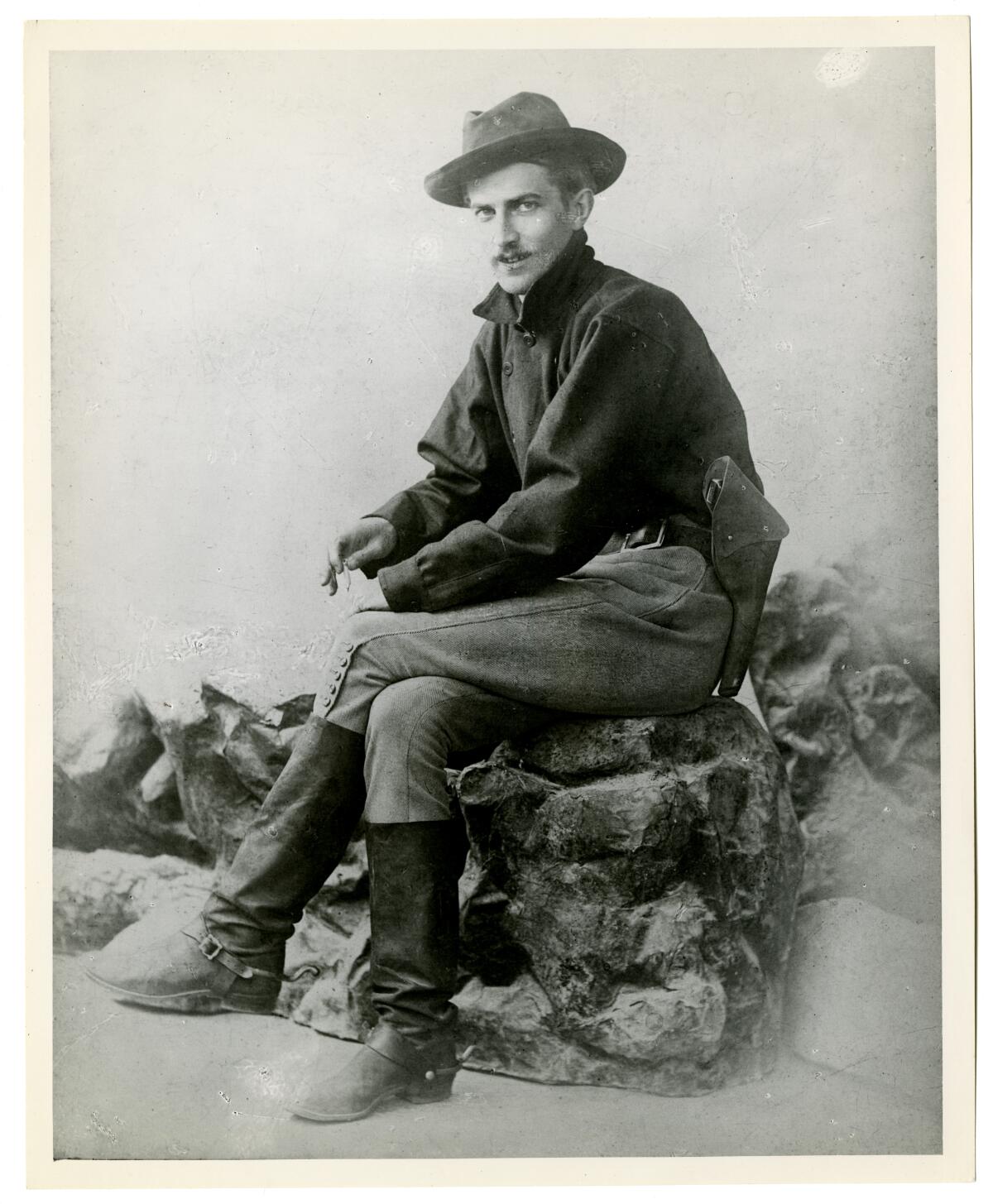

Seen through the lens of our moment, Stephen Crane can appear wildly presumptuous, a writer chronically inclined toward cultural appropriation. His first novel, 1893’s “Maggie: A Girl of the Streets,” was an effort to get into the head of a young woman in the dirt-poor Bowery, written by a well-bred New Jerseyite not long out of his teens. His most famous work, 1895’s “The Red Badge of Courage,” was a Civil War novel produced decades after the fighting ended by a writer who’d never done military service. He conjured up a Wild West he’d only passed through, imagined a Black experience he hardly knew, wrote poetry unbeholden to any tradition. Incapable of staying in his lane, he weaved into all of them.

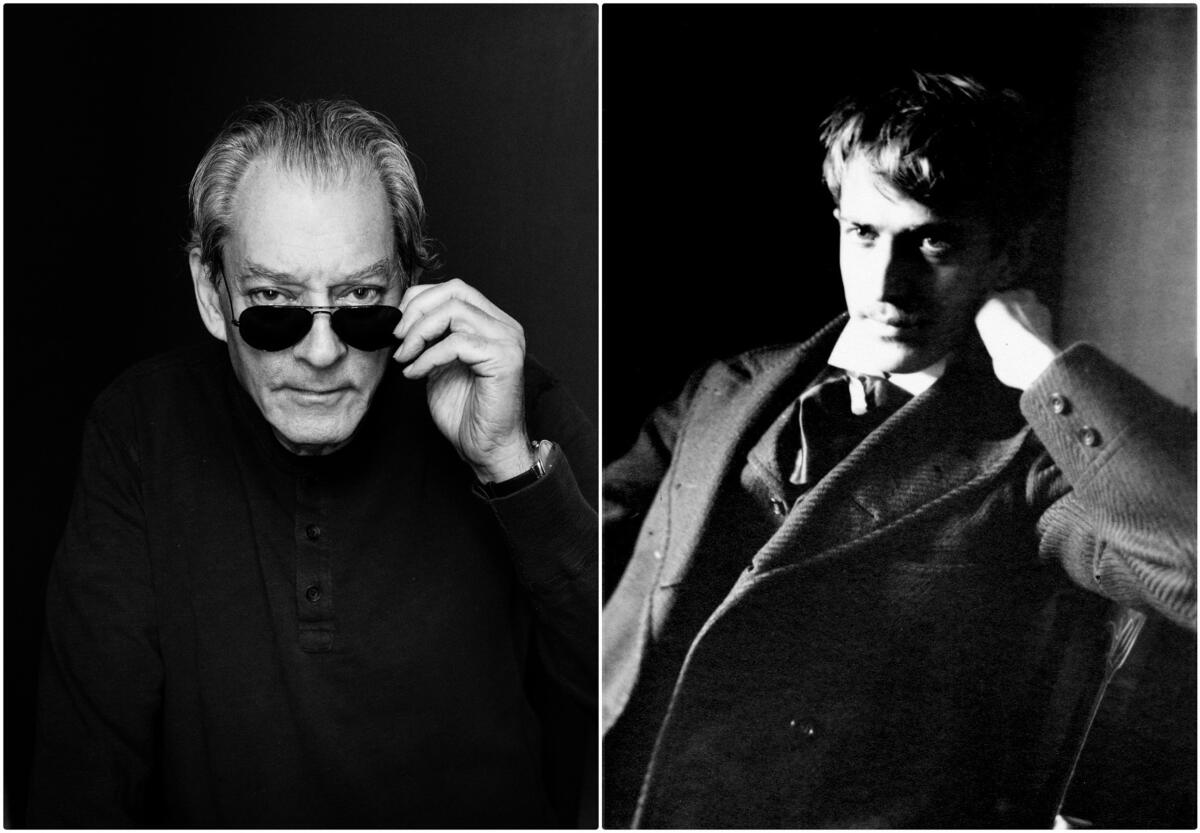

But one person’s presumptuousness is another’s winning audacity, and Crane’s overreach is among the many traits that fascinate Paul Auster, who himself has had a rich career as a novelist, poet, screenwriter and memoirist. In his bulky life of Crane, “Burning Boy,” his first biography, he’s written a book as impassioned, unconventional and frustrating as its subject.

“Burning Boy” was born, Auster explains early, out of his fear that Crane has become forgotten. If he’s right, a brief summary is in order. Born in 1871, Crane parlayed his religious upbringing and brief stint at Syracuse University into journalism gigs before venturing into fiction. “Maggie” sold poorly, but its stark vision of urban poverty caught the eye of gatekeepers like William Dean Howells. “Badge,” by contrast, sold plenty and made him a celebrity. After torching his reputation by publicly defending the honor of an alleged prostitute, he left America to report on wars in Cuba and Crete. He fell in love, headed to England, churned out reams of prose of varying quality in a desperate bid to make ends meet and died of tuberculosis in 1900. He was 28.

Practically speaking, there’s no need for a new book detailing this. Paul Sorrentino’s definitive biography, “Stephen Crane: A Life of Fire,” appeared just seven years ago. Auster delivers no new revelations or freshly unearthed documents that would argue for an update. The biographical portions of “Burning Boy” mainly tour regions already mapped by Sorrentino and other scholars.

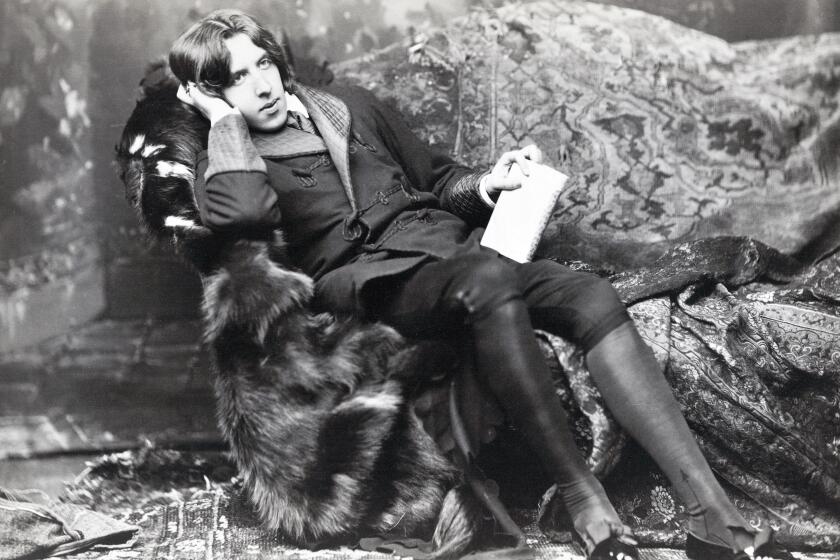

Matthew Sturgis’ “Oscar Wilde: A Life” exceeds its predecessors on two fronts — sketching late Victorian London and chronicling Wilde’s sad downfall.

Auster makes the case for his book’s existence, first, by his sheer enthusiasm for Crane, whom he calls “the first American modernist, the man most responsible for changing the way we see the world through the lens of the written word.” Reading “Maggie” and especially “Badge,” Auster reveals a writer who explored imagery, sentence structure and point of view in ways that are pioneering and magical in themselves. Auster’s rhapsodic treatments of his favorite Crane works — which don’t always overlap with the critical consensus — can be infectious. He calls “George’s Mother,” Crane’s 1896 sequel to “Maggie,” “the second half of a two-part hymn to a world in which even God is on the rolls of the unemployed.”

The book’s heft is due to its second distinguishing quality: Auster’s close — very close — readings of Crane’s signature works. “Badge,” the quintessential one-sitting classic, is given a walk-through of more than 30 dense pages; “The Open Boat,” an indelible short story inspired by Crane’s survival of a shipwreck off the coast of Cuba, earns an 18-page assessment, longer than its source. Auster wants you to read Crane so badly that he’ll bend over backward to spotlight lengthy passages. “Burning Boy” is literary biography’s equivalent of a carpet store that brings the samples direct to your home.

The strategy often works: At its best, “Burning Boy” delivers the uncanny sense of simultaneously inhabiting Crane’s prose while reading about it. The book’s chief pleasure is the experience of a veteran novelist going deep on another fiction writer, much as Vladimir Nabokov did in his lectures on Dickens and Austen. No doubt, Auster feels a kinship with Crane — a New Yorker, a baseball fan, a writer comfortable tweaking genre. Just as Crane shifted from war reportage to black-hearted poems, Auster has pivoted from the noir-inspired “New York Trilogy” to abstract, Beckett-esque works like “Travels in the Scriptorium.”

And like Crane, Auster is a deliberate craftsman, alert to the way simple sentences can do a lot of load-bearing work in terms of symbol and message. He notices the fugue-like structure of “The Open Boat” and the bigger themes that defined his later work as tuberculosis began to lay him low. In his 2017 novel, “4 3 2 1,” Auster imagined the shifting fates of characters based on differing circumstances, and he’s enchanted by Crane’s similar vision of how a host of social forces shape character. As Crane put it, “every sin is the result of a collaboration,” an insight Auster finds so profound he insists “no American writer since then has formulated anything that surpasses it.”

A long novel is something thought to be a serious novel.

No writer? Not one, in a century and change? Auster does tend to put a lot of weight on Crane’s young shoulders. He is “America’s answer to Keats and Shelley, to Schubert and Mozart.” “Badge,” he writes, predicts the existential milieu of “No Exit.” The short story “Mr. Binks’ Day Off” presages nothing less than Joyce’s “Dubliners.” “The Third Violet,” a minor, dialogue-heavy 1897 novel Auster subjects to 30-plus pages of scrutiny, is not just “the world’s first screenplay” but “probably the world’s first postmodern novel as well.” Even “Active Service,” a dismal 1899 potboiler, is “a nonsense frolic similar to a host of MGM films from the 1930s starring Clark Gable.”

It’s a provocation, verging on critical malpractice, to make outsize claims for Crane as the universe’s real first scriptwriter (not Shakespeare?) or postmodernist (“Tristram Shandy”?). Auster wants to privilege Crane’s audacity in the hopes of installing him in the American pantheon alongside Melville, Whitman and Dickinson. Yet “Burning Boy” succeeds less as an argument for Crane’s canonization than as a showcase for how complicated canons can be. Crane’s work was, considering his youth and all the dross in it, unfinished. He bucks against any effort to make him cohesive; his greatness was undermined by his financial desperation. Great writers mature, but Crane’s potential was cut short at the age of many overdosed rock stars. At the top of his game, Crane was brilliant, but only a longer, more consistent career could have crystallized him.

Auster doesn’t overstate Crane’s talent. But he does want to keep underscoring it, over and over. In that regard, “Burning Boy” reads more like a poignant lament than a life. The pages expand as if Auster keeps hoping his subject will come into clear view. He’s desperate to keep his subject alive just a bit longer. To pretend — as much as a biographer honestly can — that his hero’s end never arrived.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.