Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

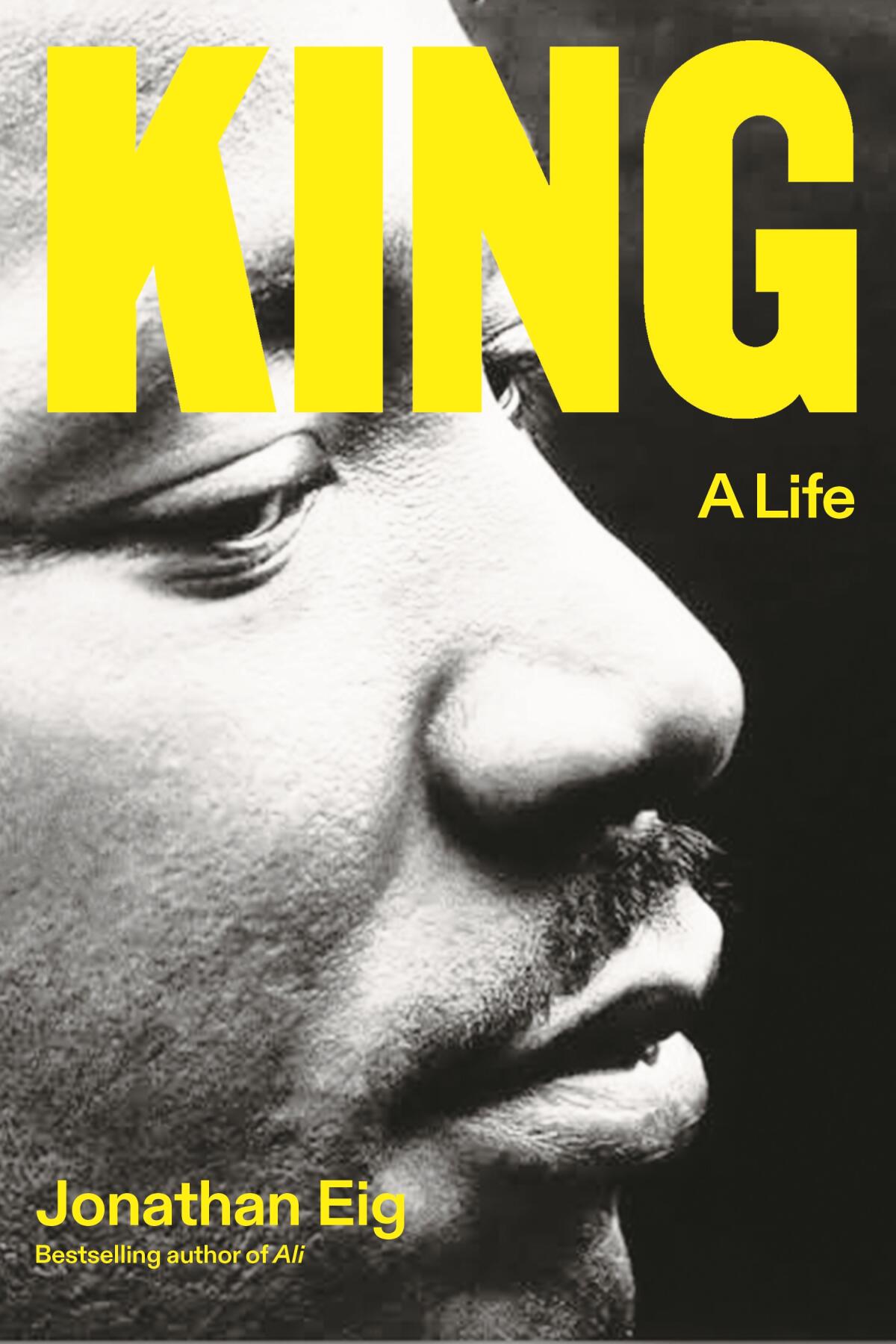

On the Shelf

King: A Life

By Jonathan Eig

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 688 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The idea came to Jonathan Eig as he was researching “Ali: A Life,” the bestseller that won the 2018 PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing. It seemed that everyone he interviewed for that book — Harry Belafonte, Dick Gregory, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young — wanted to talk as much about the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as Muhammad Ali. Initially, Eig thought about compiling an oral history of the civil rights leader. Then, he realized how long it had been since the last straight King biography. And so he set about climbing the tallest mountain of his career.

“It was hugely intimidating,” Eig says in a video interview from his home in Chicago. “Every biography is intimidating, because you’re taking someone’s life in your hands. But King was the most intimidating of them all, because it’s such a big subject. He’s an icon. He’s a saint to many people, and he’s complicated. There’s been a lot of great scholarship. I just tried not to think about all that too much, or else I would’ve maybe not even tried.”

If you’re going to write a book about King, you’d best come up with something new, and Eig’s “King: A Life,” the first such bio since Stephen B. Oates’ “Let the Trumpet Sound” in 1982, meets that mandate.

The author, who started his career as a newspaper and magazine journalist, draws from materials that weren’t available to previous biographers, including recently declassified FBI documents (which bring J. Edgar Hoover’s obsession with King into even sharper focus), an unpublished manuscript from King’s father, the papers of King’s personal archivist and more. Eig finds further proof that King had a plagiarism problem dating back to high school; he also discovers that an oft-quoted King criticism of Malcolm X, from a Playboy interview conducted by Alex Haley, was likely fabricated.

As a new biography comes out, a look back at the history of Malcolm X histories, from ‘The Autobiography’” to Public Enemy to Manning Marable.

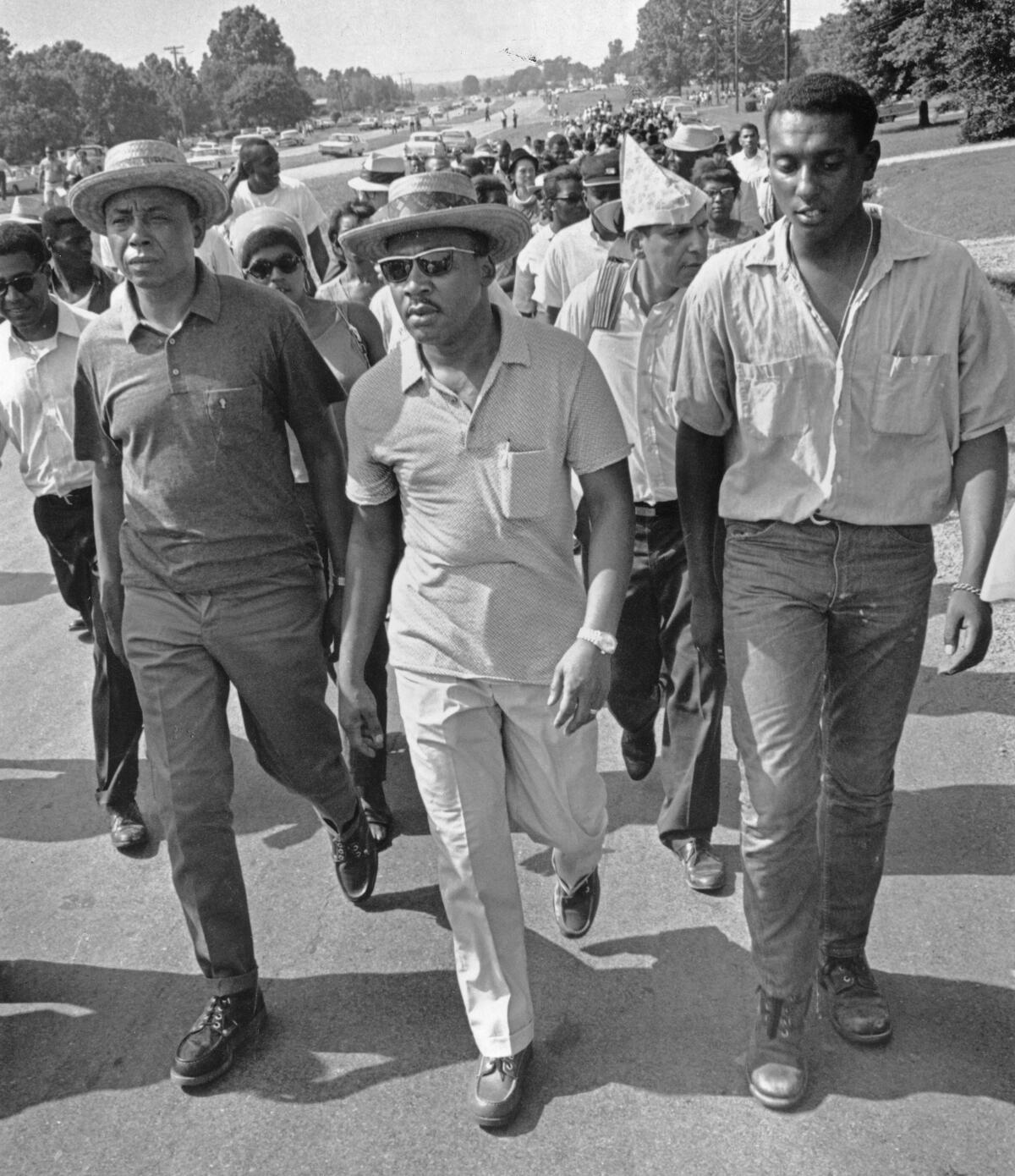

But he delivers all of this in the service of a thorough biographical study, not gotcha theatrics. What really comes across is a sense of how exhausting it must have been to be King: to always know your next breath could well be your last; to withstand pressures and hostilities from allies and enemies alike; to lead a movement defined by urgency, necessity and danger — in short, to embrace the burden and torment of being chosen.

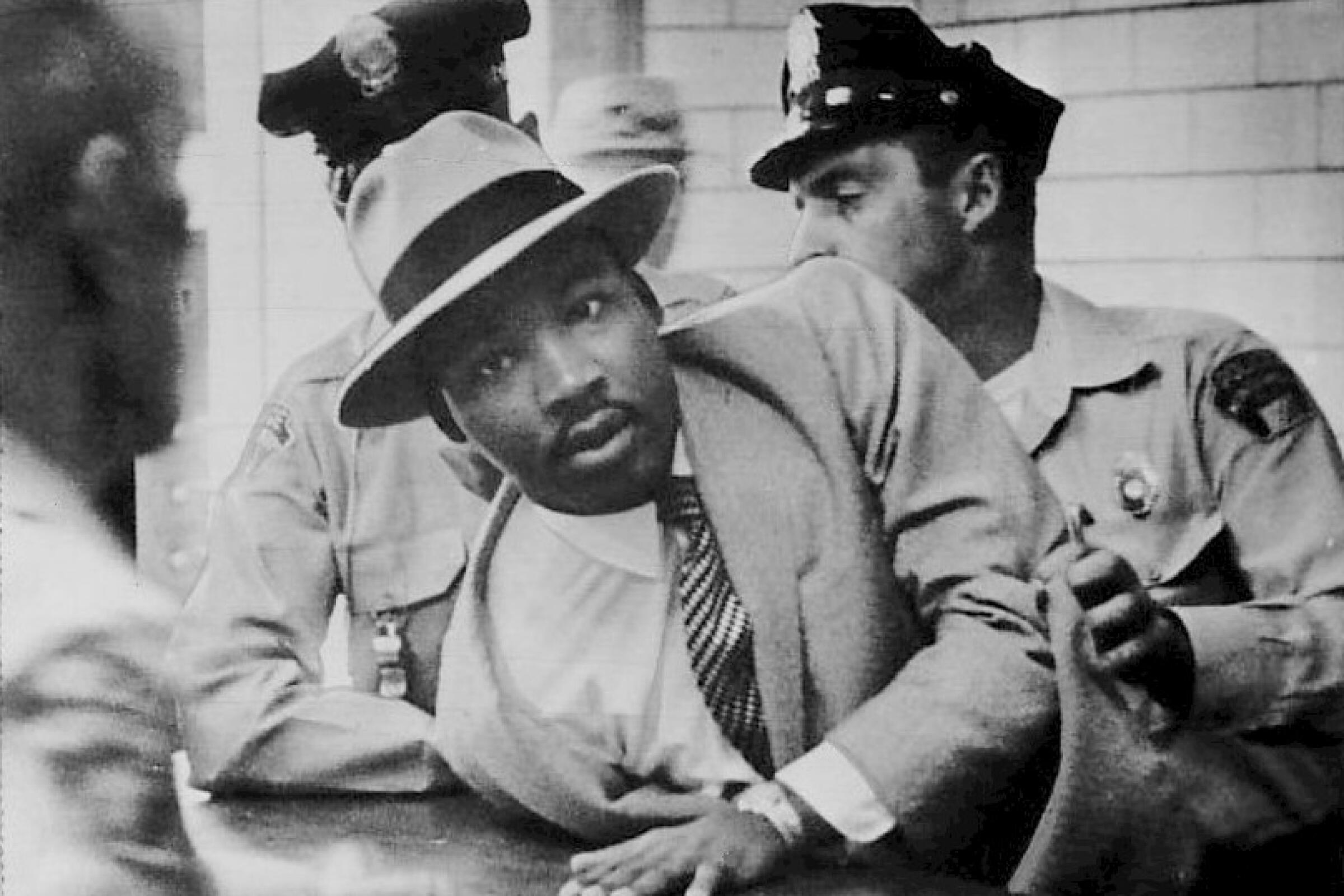

From the day he was tabbed to lead the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama in 1955 to the moment he was taken down by an assassin’s bullet in 1968, King never stopped moving, evolving and fighting, at least insofar as his spiritual commitment to nonviolence would allow.

Eig, who has also written books about Lou Gehrig and the birth control pill, was struck by the weight King carried on his shoulders, the whirlwind of a life that found him hospitalized more than once for depression and exhaustion.

“He can never say ‘no,’” Eig notes. “There are riots in Los Angeles; he’s got to go. They call on him to come to Albany, Ga.; he’s got to go. It’s one of his great flaws and also one of his great strengths. He’s willing to try anything. He throws himself into situations, trusting that something good will come from it.”

A.J. Baime sought to remedy a great civil rights leader’s erasure in “White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret.”

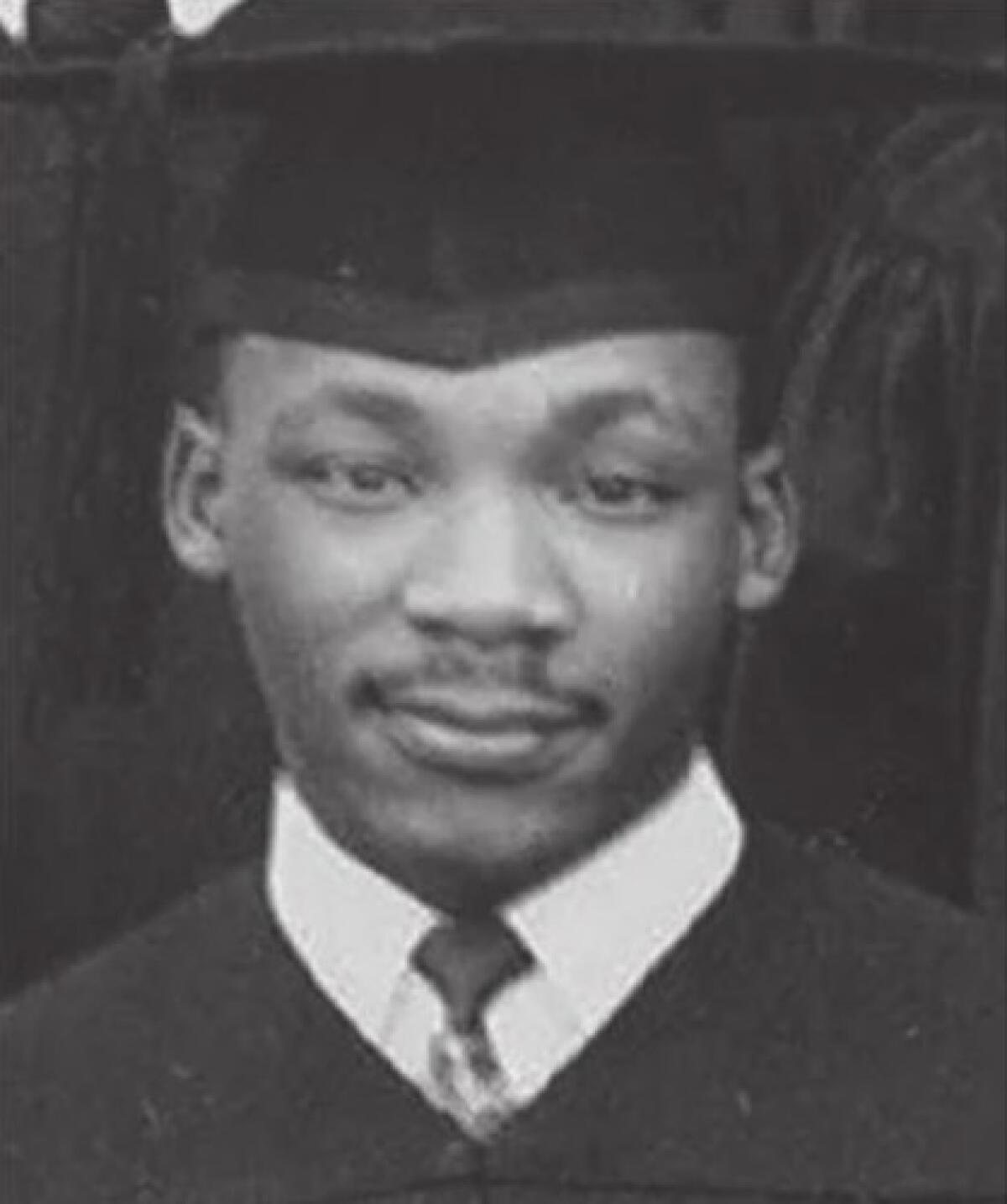

This wasn’t really the plan, any more than Saul of Tarsus planned to become Paul the Apostle on the road to Damascus. Yes, King wanted to fight Jim Crow. But he planned on doing so by following in his father’s footsteps as a Baptist minister or perhaps as a professor (he received a PhD in systematic theology from Boston University in 1955). Yes, he was always ambitious, skipping grades in school and occasionally even cribbing from other people’s work.

Still, he didn’t set out to become the leader of an international movement for racial justice. King landed in Montgomery, Ala., to minister at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, fresh from graduate school and just in time to show he had the mettle and charisma to lead the bus boycott. He found his voice immediately, and the rest is civil rights history.

Eig lays out his intent from the start. “This book seeks to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography,” he writes. “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him, replacing his complicated politics and philosophy with catchphrases that suit one ideology or another … we’ve forgotten that his approach was more aggressive than anything the country had seen — that he used peaceful protest as a lever to force those in power to give up many of the privileges they’d hoarded.”

A new edition of 1974’s “Angela Davis: An Autobiography” features a new introduction from Davis that reinforces its relevance today.

The portrait isn’t always pretty. The book contains new details on King’s serial philandering, which the FBI chronicled with near-pornographic zeal. And it takes note of King’s plagiarism habit. On this score, Eig is somewhat conciliatory. “Some people would say for a Baptist preacher, it’s not as big a flaw as it would be for an academic or college professor,” the author says. “Like jazz musicians, they borrow. They repeat phrases and make them their own. But King did it a lot, and he did it in an academic setting too, which is problematic.”

The flaws are part of the man, and Eig sees humanizing King as a crucial mission.

“I think it’s important that we treat all of our historical figures as human beings so that we can relate to them in a way that makes it possible to think about doing things with our own lives,” he says. “We don’t really do our heroes any good by turning them into mythological figures. But in King’s case in particular, I feel like the national holiday and the monument in Washington have really flattened him. We only know ‘I Have a Dream.’ We see this giant figure carved out of stone and we forget that he chewed his fingernails and that he suffered from anxiety and that he had doubts. How can we really gain inspiration from him if we don’t treat him as a real person?”

The King who emerges from these pages begins as serious-minded but playful, a ladies’ man who likes a good party and an all-night bull session. He lives in the shadow of his father, a prominent Atlanta minister, and worries about carving out a space of his own. We see these traits throughout his brief life — King was just 39 when he was assassinated — but from the start of his career, he belonged more to the movement and to history than to himself. He rarely slept as the years progressed and hardly had any quiet family time at all.

His was a difficult, often tormented path. Eig wants readers to absorb just how much and how often King put everything on the line. He also suggests that such efforts remain instructive in the here and now, especially amid organized and widespread efforts to whitewash American history.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

“His story reminds us that we need to embrace radical ideas,” Eig says. “We need to embrace change and not be afraid of it, not be afraid to reckon with the fact that we have problems and that our country was built on slavery. Don’t run away from teaching those things. Let’s talk about them.”

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.