Review: Angela Davis revises herself. She’s never mattered more

- Share via

On the Shelf

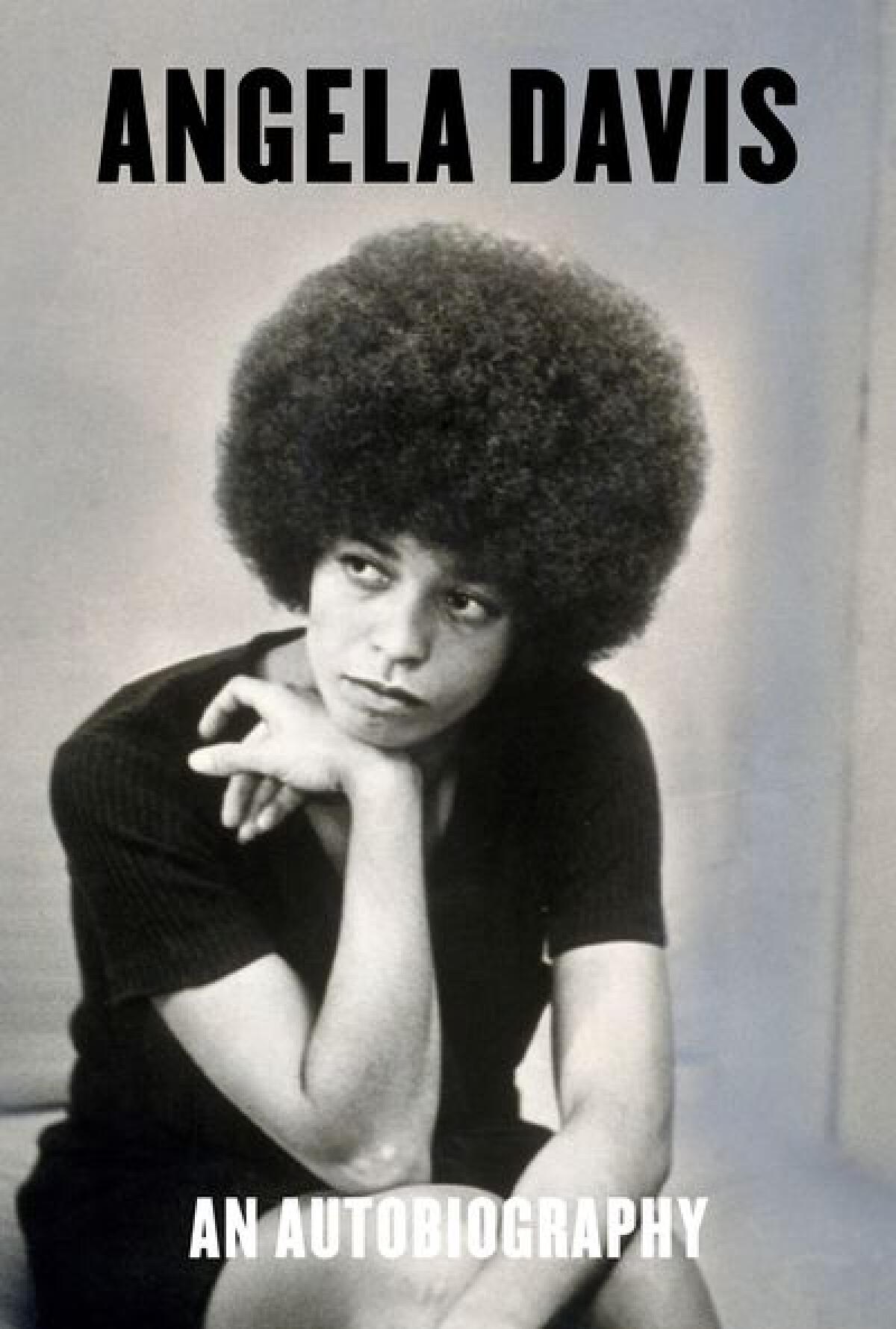

Angela Davis: An Autobiography

By Angela Davis

Haymarket: 420 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Twenty-eight is young to write a memoir. Nearly 50 years on is a long time for a memoir to be reprinted. In a new edition of the classic “Angela Davis: An Autobiography,” readers get something of a unicorn: A period account of living through the late ’60s and early ’70s that still feels vital and relevant two decades into the 21st century.

First published in 1974, when Davis was at the height of her initial fame, this update includes the original memoir, the perfunctory introduction to the 1988 second edition and yet another, longer intro written for this version. The new preface sketches out Davis’ life since then as an activist and academic, self-critically assesses the book’s limitations and, most important, links its long-ago events to the recent Black Lives Matter protests as a signpost for today’s activists.

For many readers younger than 50, the name Angela Davis probably registers vaguely, but it is worth remembering who she was, because she has something to say to us today.

It is hard now to convey what a sensation Davis was in the early 1970s. Born in 1944 and raised in Birmingham, Ala. (where she knew the four girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963), she finished high school at the integrated Elisabeth Irwin School in New York, graduated from Brandeis and earned a PhD in philosophy from Berlin’s Humboldt University. She first became well known in 1969, when at the instigation of California’s then-governor, Ronald Reagan, UCLA fired Davis, then a lecturer in the philosophy department, for being a member of the Communist Party. When a court ruled that that was illegal, the university fired her again on the grounds that she’d used inflammatory language.

But her greatest notoriety came the following year. In 1970, Jonathan Jackson took five hostages in the Marin County courthouse in an attempt to free his brother, one of three inmates, known as the Soledad Brothers, charged in the death of a guard at the California prison. In the ensuing melee, four people were killed, including Jackson and a judge. Davis, who led the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee, had purchased the guns used in the escape attempt. Authorities charged her with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy. (She maintained that Jackson had taken the guns without her knowledge.) Davis went underground but was captured a couple months later. Awaiting trial, she was held for 14 months without bail.

Jon Meacham’s “His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope” honors Lewis’ resistance but leaves out the hard work that got us here.

The case made her a cause célèbre. “Free Angela Davis” became a rallying cry for the young on the left. Protests were held in support. A plane hijacker made her release one of his demands. The Rolling Stones and John and Yoko wrote songs about her.

In early 1972, Davis’ lawyers managed to get her released on bail. In June, she was acquitted of all charges, with the jury finding that she was not at all involved in the courthouse ambush. Davis went on an international speaking tour and became involved in numerous political causes; her autobiography was published in 1974.

As Davis herself notes in the new edition, the book is more a political coming-of-age story than a traditional memoir. Indeed, she initially declined the offer to write it, not wanting “to contribute to the already widespread tendency to personalize and individualize history.” But her editor — Toni Morrison, by the way — convinced her of the value of doing a political memoir. Even more than that, though, the book is better seen as falling in the long tradition of prison diaries.

Prison was a formative experience for Davis. She opens with a long section on her flight underground, her capture and her first months behind bars before doubling back to her early years and then returning to her trial and prison time. It is in these sections that the book really comes alive. There’s an immediacy to her writing, her descriptions of life behind bars tactile and engrossing.

Davis movingly recalls seeing a prisoner going into labor alone in a hallway and details the untreated or overmedicated psychological problems of inmates. She vividly captures the inhumane conditions and the prison culture of banding together into “families” for mutual support.

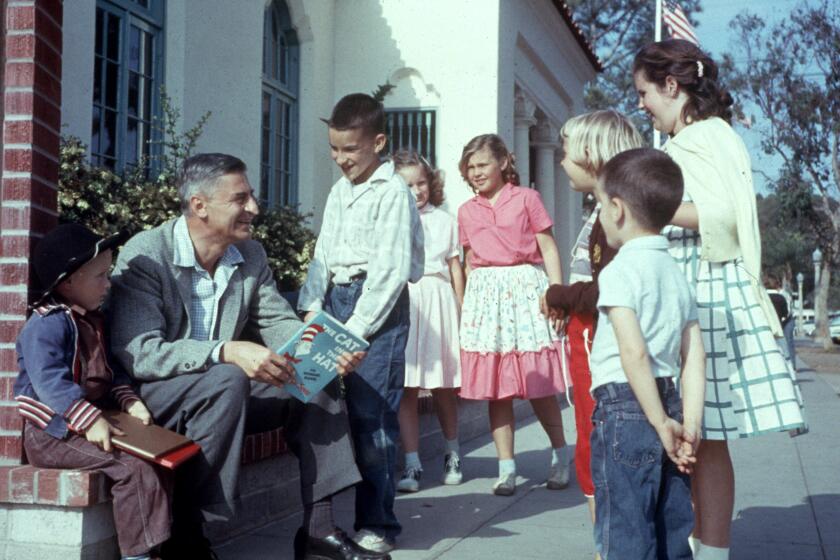

Her descriptions of homosexual relations behind the prison walls are cringeworthy to contemporary ears. Davis acknowledges in the new introduction that the way she “uncritically embraced homophobic premises” sticks out like a sore thumb. (Ditto with her inchoate feminism, which she fleshes out substantially now). She should be applauded for leaving in the old material, especially at a time of quick flareups over old work by everyone from Dr. Seuss to Norman Mailer; fortunately, she is still around to place them in context and evolved (or savvy) enough to own up to early blind spots.

The pivot from Dr. Seuss’ books during a national event founded to honor him seems sudden, but for the NEA and local teachers it was a long time coming.

Yet in her critique of the carceral system, Davis has always been far ahead of the curve. The era of harsh and punitive incarceration that was nascent when she was in prison and that peaked in the ’90s appears to be coming to an end, and in recent years, Davis’ views have become mainstream. She should be an inspiration for today’s prison reformers for the ways she both humanizes the incarcerated and embeds their experience within the larger structural inequalities of American society.

The middle chapters are ... fine. They are at their best when they are personal and specific. The sections on growing up in the South during the early civil rights movement, on being one of the only Black women at college and on her protesting in the late ’60s are great. It is when she describes her intellectual journey that the book falls flat. Partly it comes down to changing times — the eclipse of Communism, though it survives as a straw man — and partly it’s a young ideologue’s tendency to get mired in political abstractions.

Yet, in practice, Davis’ views on racism and political activism remain acutely relevant. As she observes in the intro, the book “pivots around state violence: the violence of the police, the violence of jails and prisons and the complicated ways these forms of violence infuse the communities they target.” In the wake of Trayvon Martin and George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, this is an important observation. There’s a tendency to see these deaths as the result of individual wrongdoing, rather than the product of bad laws and flawed policing. Davis’ story and the long arc that connects 1972 to 2022 are a stark reminder of how deeply embedded these problems are in American life.

“My contribution, like the work of others who have attempted to narrate aspects of the anti-racist struggle, will hopefully help us better understand the world today,” Davis writes now. “Angela Davis: An Autobiography” continues to fulfill that goal as the rare book that even almost 50 years later feels timely and relevant. Maybe too relevant, considering how little has changed in the interim.

As a new biography comes out, a look back at the history of Malcolm X histories, from ‘The Autobiography’” to Public Enemy to Manning Marable.

Lewis is the author of “The Shadows of Youth: The Remarkable Journey of the Civil Rights Generation,” among other books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.