L.A. author Carribean Fragoza wins prestigious $50,000 Whiting Award

- Share via

When a phone call from an unidentified number turned up on Carribean Fragoza’s cell, she immediately assumed it was a spammer and didn’t pick up. But the phone kept ringing, so she finally answered. “Don’t hang up,” she remembers the voice on the line telling her. “This is the Whiting Foundation.” They were calling to let her know that she had been selected for a 2023 Whiting Award, a $50,000 unrestricted grant for emerging writers. Fragoza says she ended up “crying on the phone.”

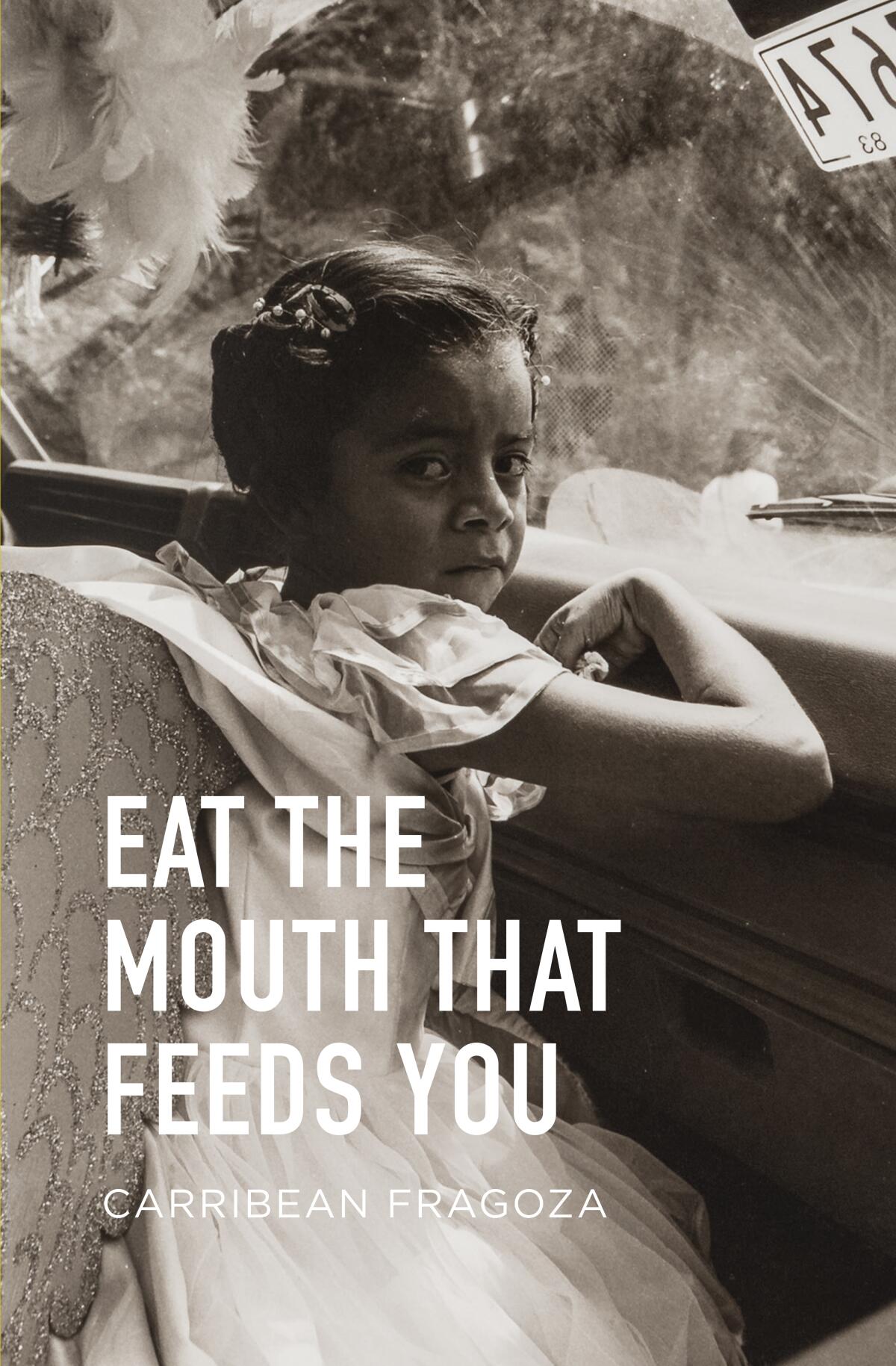

Fragoza, a writer whose short story collection, “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You,” received wide acclaim when it was published two years ago, is one of 10 authors to receive the prestigious prize this year — and the only one from the Los Angeles area.

Fragoza was among 10 Whiting Award winners announced Wednesday evening during a ceremony in New York. Over its 38-year history, the prize has frequently served as a harbinger of future literary success. Past winners have included novelists Colson Whitehead and Victor LaValle, playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and poet and novelist Ocean Vuong. In addition to Fragoza, this year’s recipients include dramatists Mia Chung and Emma Wipperman (who is also a poet), fiction writers Marcia Douglas and Sidik Fofana, graphic novelist R. Kikuo Johnson, poets Tommye Blount and Ama Codjoe, and journalists Linda Kinstler and Stephania Taladrid.

Fragoza is a fiction writer, essayist and journalist from El Monte who attended UCLA and CalArts. Over the years her writing regularly appeared in publications such as LA Weekly and the L.A. Review of Books. (I came to know her through art circles more than half a dozen years ago, when she was a regular contributor to KCET’s Artbound, writing on topics including art and gentrification.)

In early 2020, with three other writers — Alexa Sayf Cumming, Ryan Reft and Romeo Guzman (a historian who is also Fragoza’s husband) — she co-edited the essay collection “East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte,” a kaleidoscopic portrait of life in a Latino L.A. exurb that doesn’t generally get much air time. “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You,” released a year later, immediately drew plaudits for its deadpan surrealism and its focus on the lives of young Chicanas. The New York Times hailed her as “a forceful new voice in American literature.”

Carribean Fragoza’s “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You” is a debut story collection ripe with surrealism but grounded in the soil of Latina experience.

On Monday, Fragoza took time out of her schedule — she currently teaches at CalArts — to talk about the prize and the writing life. In this conversation (which has been condensed and edited for clarity) she talks about the novel she would really like to finish and why she is so intrigued by the dark recesses of women’s minds.

Where does the novel stand? And will the Whiting help?

I worked on it a bunch during the winter break and I felt if I could spend one solid semester working on it, I could do it. It was hard to know when I would get that time. Now that I have this grant, I’m going to try to work on it this summer and into the fall. I think I can do it by the end of this year. I’ve been saying that for a while, but this year I mean it.

What can you tell us about it?

It’s about a girl who disappears — briefly. Her mother is looking for her. The police don’t take her seriously. She thinks horrible things might have happened because of the reality of girls of color disappearing and the police not taking it seriously. But the daughter has joined an environmentalist group of radical birdwatchers and they take over a natural reserve. At the center of the book is this mother and daughter and this complicated relationship. And it’s set in an immigrant working-class neighborhood a lot like El Monte.

From a bestselling migration memoir to an acclaimed novel of suburbia, political poetry and essays and on and on, Salvadoran writers are having a big moment.

What first drew you to fiction?

I lived in a very small house with my siblings and my parents. Living in a small house, there’s not a lot of space to grow. Books gave me that space, and fiction, in particular, gave me the space to explore. I started writing stories as a kid. Also important were those stories that your family tells you. I grew up on La Llorona and the Chupacabra, that oral tradition of storytelling from my cousins, my tías, my grandparents.

What was the first Carribean Fragoza short story?

It was fantasy. It was this princess and she was really frigid, everyone was trying to warm her up and pierce through her icy heart. The project was to write a story and illustrate a book. I bound my own book in glittery purple paper. My mom has it still — it’s in the garage.

You’ve talked about creating your own canon as a Chicana. Who inhabits your canon?

From the earliest days, Helena María Viramontes and “The Moths” [from the collection “The Moths and Other Stories”]. Then Gabriel García Márquez, of course. And Salvador Plascencia, an El Monte writer who was a huge discovery for me — to find his book and see those elements of magical realism but recast in my neighborhood. It’s called “The People of Paper.” It’s a cool, strange magical book. There’s also those weird stories by Leonora Carrington. She has these bizarre stories that I really dig.

How do you feel about the label of magical realism being applied to your work? It can be a freighted term — often applied to any Latino writer who channels a bit of the otherworldly.

It’s an imperfect label. I think it serves a purpose. It’s a fast and easy way for people get a really general idea of the magical aspects and the surreal aspects in the work — and I guess I’m OK with that. If a reader is willing to continue entering the work and know that it’s not going to be a Gabriel García Márquez work, that it’s going to be its own thing, that’s fine. I don’t get as mad about it as other folks. There are terms that have been tossed at my book like “speculative” and I don’t think that sticks.

Labels aside, I’m interested in exploring the possibility of strange things happening in daily life. It’s about looking at daily life and the mundane, but through the lens of the weird.

Painter and storyteller Leonora Carrington was the kind of wild, visionary character who ought to be emblazoned on our cultural memory.

I would love to know about your process. What’s the genesis of a story for you? A character? A setting?

It’s usually a voice. If I can hear and write the voice pretty clearly, then I follow that voice. Sometimes, it’s not a specific voice but an idea. “Ini y Fati,” the story I wrote about the child martyr/saint that befriends a little girl, that came from the idea of a virgin child who was murdered several hundred years ago and comes back for vengeance on the ass— of the world. I wanted to imagine what that would look like.

Your stories center on women and girls. What aspects of female interiority are you intrigued by as a writer?

Two things: I’m thinking of the interior life of girls, of young women, teenagers, and also the interior lives of mothers. It’s vastly overlooked. Girls, even if they’re not sexually active, they’re exploring what their sexuality is and that can scare people. And maybe it’s the goth-iness in me, but I’m interested in the darkness. I don’t mean that in a malevolent way. Just the darker, more complex emotions of girls. It’s not all sunny bows. I am fascinated by the scowl, the unsmiling aspect of little girls, when they’re young enough that they can’t be made to smile if they don’t want to. I’m interested in protecting that.

Then there is the aspect of mothering. What is the interior life of a mother? That was a mystery before I became a mother. And it’s a mystery to me now. I did have a good relationship with my mother, but there were limits of understanding to what her experience was and what her mother’s experience and my great grandmother’s experience was. It is not always talked about — our challenges and emotional lives. It’s still a process of discovery for me.

Muñoz’s stories are peopled by furtive figures who grapple with survival and loss. His most stunning depiction, however, is of the Central Valley itself

What are you reading right now? And what will you be reading next?

I recently read Marytza Rubio‘s collection of short stories. She’s a chica from Santa Ana and her book is called “Maria, Maria and Other Stories.” Someone called it tropi-goth and that is suitable. I also recently returned to Leonora Carrington. And there’s a collection by Yuri Herrera that’s about to come out that I’m really excited about, [“Ten Planets: Stories”], and Vickie Vértiz has a new collection of poems that came out [“Auto/Body”].

I’m also itching to read “Nightcrawling” by Leila Mottley. I heard her talk at AWP, [the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Conference & Bookfair], and she’s brilliant. Those are the things I’m really excited to read.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.