Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There’s a movement afoot — if you know where to look.

For too long, the American literary industry has discussed El Salvador and its people through the gaze of cultural outsiders. But that has started to change, with an explosion of writing by Salvadorans in the United States — especially those with ties to California.

These works range from a memoir detailing Central American migration to a novel of suburban reckoning, from essays and poems to academic works and even a cookbook. The past couple years have led up to what Felix Cruz, a publicist for Random House, calls the “Salvadoran Renaissance in literature.” To Cruz, what matters most is “moving beyond tropes and monoliths” to tell stories from within the community. “With nuance and nerve, these writers are articulating both the depth of wounds and the integrative power in healing our community yearns for.”

In 2022, this renaissance became undeniable. Javier Zamora’s “Solito,” a debut memoir following his trek to the United States at age 9, hit the New York Times bestseller list in September. Like all successes, it was years in the making — built in part through Zamora’s work as co-founder of Undocupoets, a much needed beacon and resource for migrant writers.

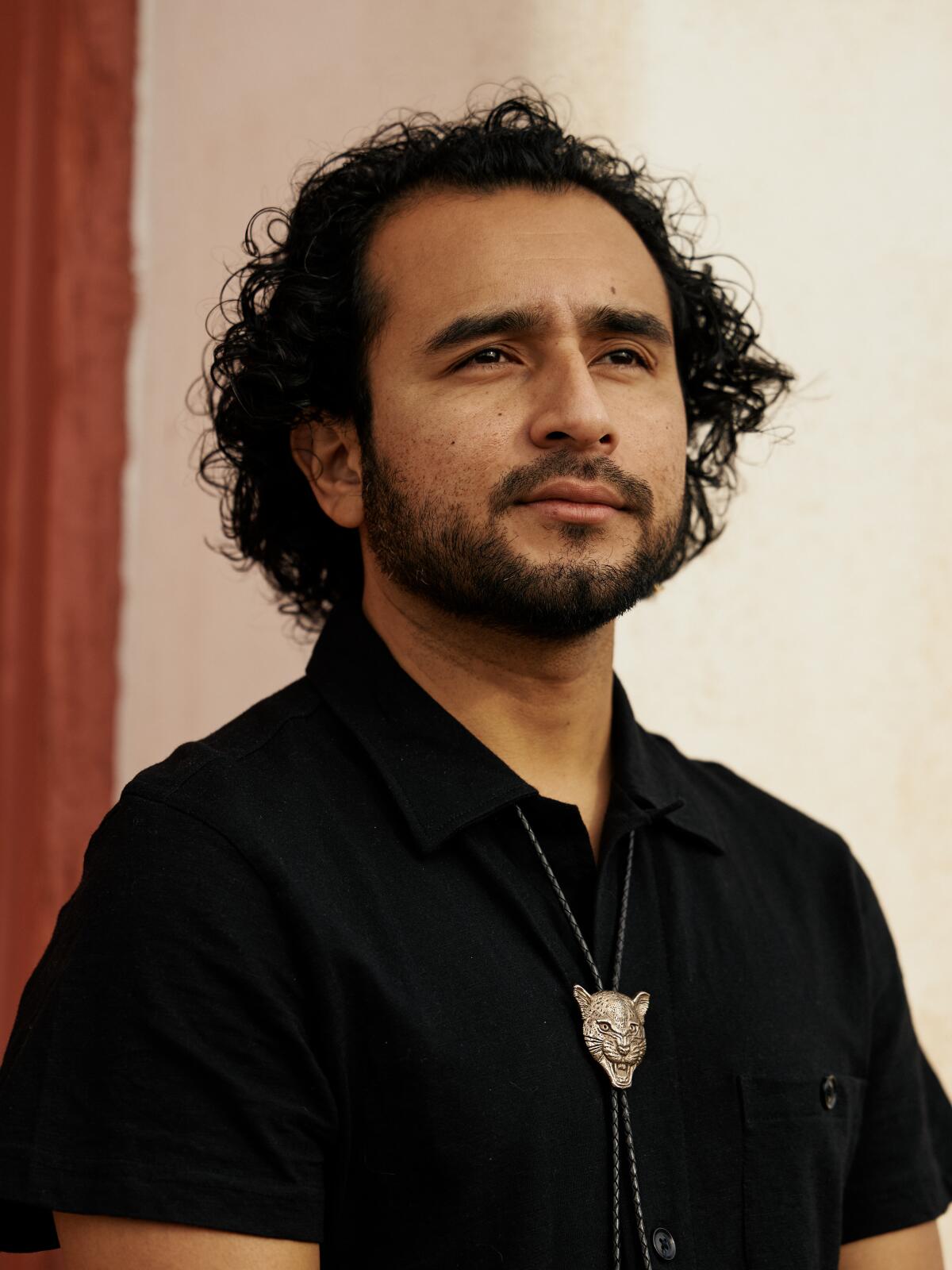

Even as “Solito” was topping the lists, another breakthrough writer was announced as a National Book Award finalist. “The Town of Babylon,” a debut novel by Salvadoran Colombian Alejandro Varela, follows a queer man confronting his past during his 20th high school reunion in his suburban hometown. Varela’s second book, “The People Who Report More Stress,” a short-story collection, will be out this April.

Javier Zamora talks about “Solito,” his harrowing memoir about journeying from El Salvador to the U.S. as an unaccompanied 9-year-old.

These bigger releases only scratch the surface of the Salvadoran Renaissance, which spans not only experiences but regions, including El Salvador itself. Poet Alexandra Lytton Regalado grew up in Miami and then moved back to El Salvador — where she continues to write, edit and organize spaces for writers across borders and languages. From San Salvador, last year she published her second book of poems, “Relinquenda,” a meditative collection written after her father’s death, which won the prestigious National Poetry Series competition.

Raquel Gutiérrez, born in Los Angeles to Mexican and Salvadoran parents, recently published their debut, “Brown Neon,” a sprawling collection of essays on topics including the border wall and the relationships among L.A.’s punks and artists. Gutiérrez writes of the American Southwest with care, precision and a wealth of knowledge that enriches the broader canons of queer, Latino and Los Angeles literature.

L.A. is a particular hotbed of Salvadoran literature. Among its other standouts is Cynthia Guardado, a poet from Inglewood who published her second collection, “Cenizas,” last year. Her verse mixes family and personal histories, bounces between nations and covers the U.S.-funded civil war in El Salvador, which lasted through the 1980s. At its core is an essential question: How should the generation after a war relate to the violence that has preceded us, and where do we go next?

Forthcoming releases promise to keep up the momentum. Last October, Ruben Reyes Jr. made a two-book deal to publish a set of stories, “There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven,” and a novel, “Archive of Unknown Universes,” which will employ surrealism and dystopian tropes to explore Central American identity.

In “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas,” Roberto Lovato finally tells the full story of his rebel life.

And this April, Seven Stories Press will publish “Stories and Poems of a Class Struggle,” a bilingual collection of work from the late, celebrated poet Roque Dalton. It feels apt that, nearly 50 years after his death, Dalton’s work is being reprinted alongside a burgeoning generation of Salvadoran writers. He was a revolutionary poet and part of La Generación Comprometida, one of the most important literary movements in Salvadoran history.

The successes of this new generation, along with a revival of the last, represent a potential reversal in the way many American readers have encountered the country. For decades, the American literary establishment has amplified non-Salvadorans as the key voices on Salvadoran life and hardship. The most respected to this day are Joan Didion and Carolyn Forché. In 1982, Didion spent two weeks in the country before going on to publish “Salvador,” in which she declared, “Terror is the given of the place.”

In response, Roberto Lovato — author of “Unforgetting” and another writer at the vanguard of the diaspora — wrote, “Didion’s writings about us forgot a foundational fact of Salvadoran life: our humanity.” The Hammer Museum just concluded an exhibition titled “Joan Didion: What She Means,” which displays the work of renowned Salvadoran artist Ronald Morán. Yet Morán has never met or read Didion. There has often been a disconnect between Salvadorans and those writing about them.

Forché, whose portrayal of El Salvador teeters between spectacle and saviorism, is another example of this disconnect. After visiting the country, Forché wrote one of her most famous poems, which is set in 1978 and details a conversation with a colonel who appears with a sack of human ears. The opening line of “The Colonel” was subsequently used as the title for Forché’s memoir, “What You Have Heard Is True,” a 2019 finalist for the National Book Award.

“I was told that in the United States Forché is relevant, but for writers here in El Salvador — people don’t know her,” said Alberto López Serrano, director of the Amada Libertad International Poetry Festival in El Salvador. (Amada Libertad was the pseudonym for poet and guerrilla fighter Leyla Patricia Quintana Marxelly, who was assassinated during the war.)

An exhibition at the Hammer Museum inspired by Joan Didion features historic objects as well as art. It’s sometimes tantalizing, often muddled.

None of this is to say that people without strong relations to El Salvador cannot write about it, especially regarding events that demand international attention. “In moments where there are human rights abuses, such as what is occurring in present-day El Salvador, we need everyone to speak up,” said economist Tatiana Marroquín. According to Human Rights Watch, under current President Nayib Bukele, “state security forces have committed egregious abuses, including extrajudicial executions, sexual assaults, and enforced disappearances.”

The more poignant question may be: When does the writing of a laureled outsider drown out the literary voices of the people being discussed? Fortunately, this much is starting to change. Salvadoran American writers are now telling their own stories, and they are bridging connections to writers in the homeland too.

In part, that change is a product of migration, as well as a lot of hard work. In 1980, near the start of the civil war, there were approximately 95,000 people of Salvadoran origin living in the United States. Today the Salvadoran diaspora constitutes one of the largest Latino populations in the United States — even though El Salvador is smaller than Massachusetts.

With so many living abroad, especially in the United States, contemporary Salvadoran literature is a transnational conversation encompassing myriad hybrid experiences. “We’ve had a very rigid concept of nation in the past,” said Lucia de Sola, an editor of the San Salvador-based literary publisher Editorial Kalina. “The El Salvador of today transcends borders: We have writers who live all over the world. … Our concept of a national canon is changing, which is a great thing, and long overdue.”

This shift in understanding didn’t occur overnight. It took years of groundwork and dedication from writers who have looked past their own books to also bring other voices to the forefront.

In 2017, Central American editors published the cutting-edge anthology “The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the United States.” One of its editors, Leticia Hernández-Linares, explained the gaps she was hoping to fill: “I was always curious about what my history was, as someone who didn’t grow up in El Salvador. I didn’t really see myself in the history of the United States either.”

Tatiana de la tierra, a groundbreaking bilingual writer and editor, died 10 years ago in Long Beach. It’s time to unearth her underground legacy.

That same year, the Tierra Narrative collective was founded to foster “conversations and collaborations between the Central American diaspora and the homelands.” This collective has hosted transnational and bilingual literary programming with organizations such as the Poetry Project in New York City, featuring writers based in El Salvador including Kenny Rodríguez and Lauri García Dueñas.

In the past five years, Salvadoran - American writers have increasingly risen up to mainstream literary recognition in the United States. Claudia Castro Luna served as the poet laureate of Washington state. In L.A., celebrated poet Janel Pineda published “Lineage of Rain,” while Yesika Salgado amassed a large social media following, published three collections and became one of the most recognized poets to come out of L.A. spoken word community.

Literary journals, meanwhile, provided space for Central American writers. La Piscucha Magazine, for one, was founded in 2019 by editors in El Salvador and the United States. And last year, to mark the 200th anniversary of the Federal Republic of Central America declaring independence from Spain, Bomb Magazine created a folio of writers from the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras), introduced by poet and filmmaker Daniel Flores y Ascencio. Today’s literary movement is the product of both individual talent and vast communal effort.

Jorge E. Cuéllar, a professor at Dartmouth, reflected on this generation of diasporic Salvadoran writers. “In one sense,” he said, “these works showcase the incredible talent of U.S.-based Salvadorans — the displaced, forcefully relocated, some in exile — that have taken up the literary and aesthetic traditions of their home country, sometimes their parents’ home country, as their starting point. From here, they are intervening into the U.S. literary and cultural landscape, challenging tightly held fictions. ... Without hesitation, these writers are speaking truth to power, without the need to mediate themselves through a white, U.S.-centric gaze.”

In El Salvador, meanwhile, it is still very difficult for writers to find readers in the United States even among their diasporic kin. Books published in the country usually have small print runs and face hurdles in shipping. Governmental and societal persecution of writers continues to this day. In 2015, when Jorge Galán, one of El Salvador’s most esteemed writers, published his novel “Noviembre,” a series of death threats forced him to temporarily flee the country.

Journalists in El Salvador who write about gangs can now be sent to prison. Two brothers defy the law with a story tying President Nayib Bukele to violent street gangs.

Last year, Bukele’s administration effectively criminalized writing about gangs in El Salvador — making it illegal to reproduce “statements originating or presumably originating from said criminal groups, that could generate anxiety and panic in the population.” Salvadoran writers persisted despite the censorship.

There is also a strong feminist movement in El Salvador. Poet Marielos Olivo has spoken out in defense of women imprisoned for having spontaneous abortions, and Elena Salamanca’s “Siemprevivas” has documented extraordinary women in Salvadoran history.

Salvadoran editors, including Josué Andrés Moz and Miguel Huezo Mixco, continue to publish chapbooks and anthologies that represent the finest work in Central America and the diaspora. From El Salvador to the United States, writers are pushing against systemic barriers that work to limit their reach.

Despite the obstacles, optimism feels like the only logical conclusion. We are living through one of the largest movements of Salvadoran literature in history, one that is beyond the reach of any single government or language. It is no exaggeration to call that a renaissance — just a plain fact.

Soto’s debut poetry collection, “Diaries of a Terrorist,” was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2022.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.