How Marguerite Duras shaped Nobel winner Annie Ernaux and a generation of writers

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Easy Life

By Marguerite Duras

Translated by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan

Bloomsbury: 208 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In a recent interview, Annie Ernaux, the winner of this year’s Nobel Prize for literature, said of her detractors, “They think I’m not legitimate. What disgusts them is that there are people who have found, in literature, something that speaks to them, and those people aren’t CEOs or company bosses.” Her work follows in the footsteps of a compatriot from the generation before hers: Marguerite Duras.

Ernaux’s focus, like Duras’, is the lives of women. For Ernaux, specifically, her life. Duras, who died in 1996, used fiction as a film over her novels, but many of them were autobiographical. Both writers approach the interior lives of their characters with blatant honesty, unflinching when it comes to sexuality and death. Ernaux started publishing in the mid-1970s, around the time Hélène Cixous declared, in her seminal essay “The Laugh of the Medusa,” that “women must write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions.”

Celebrity came late to both Duras and Ernaux. Duras was 70 when she published “The Lover.” Annie Ernaux is 82. What came much earlier, for both, was artistic success. This much you can glean from Duras’ second novel, written when she was 30 and now published in English for the first time as “The Easy Life.”

Duras’ writing has undergone a resurgence in popularity in the last few years thanks to writers such as Deborah Levy, who recalls Duras’ writing about writing in her memoir, “The Cost of Living,” and Kate Zambreno, who has written the introduction to “The Easy Life.” Levy and Zambreno are both daughters of Duras. Theirs is the writing of women who are not only suppressed by the men who dominate the world but also alienated from their bodies, their experience, themselves.

Yes, awarding the Nobel Prize in literature to Ernaux, a chronicler of illegal abortion, is a political move. But it’s also a victory for literature

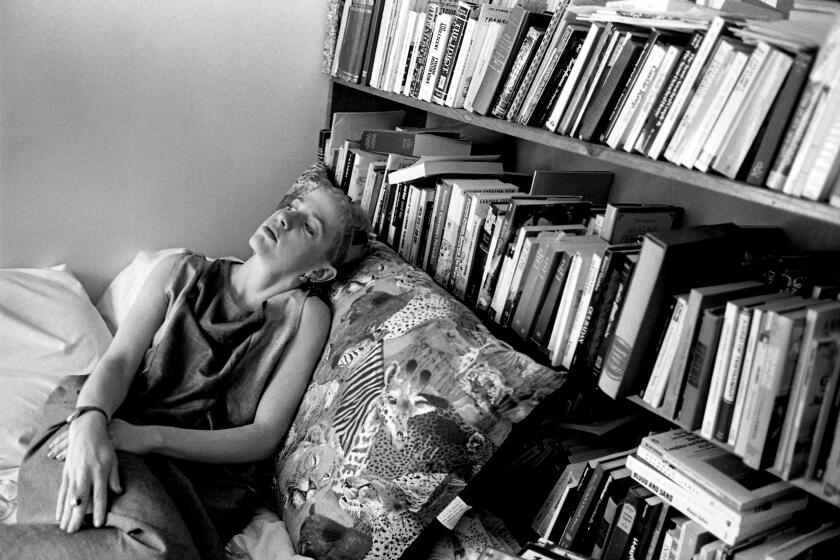

Duras produced a mountain of work, most notably “The Lover” and “The Ravishing of Lol Stein.” She survived World War II by working for Vichy book censors by day and the French Resistance at night. Her husband was sent to Buchenwald. In addition to her novels, Duras wrote screenplays, stories and plays and directed more than a dozen films. But none of this touches on my favorite writing of hers. And that is her writing about writing, collected in “Practicalities,” “Writing” and, most recently, “Me & Other Writing.”

“The Lover ” tells the story of a white Frenchwoman looking back on her teenage romance with an older Asian man. Despite its title, the novel is not a love story, but a meditation on the passage of time. Duras scoffed at the popularity of the book and its film adaptation: “It’s an airport novel,” she said. “I wrote it when I was drunk.”

Duras’ 1964 novel, “The Ravishing of Lol Stein,” also explores a woman’s obsession over the loss of a man. Lol is jilted by her fiancé at a ball, goes mad, then returns to her hometown, where she meets the lover of her married best friend. Though Lol acts interested (and even turned on) by the sexual exploits of her friend and her lover, what she’s really excited by is the opportunity to rewrite her abandonment.

In “The Cost of Living,” Levy quotes Duras as saying that in writing “Lol Stein,” she “gave herself permission to speak in a sense totally alien to women.” Anyone who has read it knows that Duras is intrigued by the people we are, the people we see in the mirror and the people we’ve been. The clues in her nonfiction are bread crumbs on the way to understanding her fiction, but more delightfully, they are about what it means to write, particularly as women.

“The Easy Life” bears all these hallmarks. Francine is a young woman who lives on a farm in France. The book opens as she watches her uncle stumble home, mortally wounded from a fight with her brother. (The uncle had been sleeping with Francine’s brother’s wife.) After a series of unfortunate events, Francine decamps to a hotel, where for the first time she becomes aware of her own existence, her own body, the beating of her heart. As the hotel is near the ocean, there are more than a few breathtaking Woolfian moments.

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

I like this novel better than both “Lol Stein” and “The Lover.” Duras’ writing here is both more honest and more subtle than her later works. Much of this may be due to the sensitive work of the translators, Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan. In a note following the text, they share a decision on the phrase “we’ll have an easy life.” In French, the phrase is, On l’aura la vie tranquille. “In French,” the translators tell us, “‘on’ resounds here as a general ‘we,’ ... though this time Francine is addressing all of her selves before she reaches home and they merge into a more decisive ‘I.’” Moments like these are among the great joys of reading works in translation.

It might be tempting to write off “The Easy Life” as a treat for the Duras-obsessed — a minor discovery for fans. But the presence of Duras’ influence in the work of writers such as Ernaux, Zambreno, Chris Kraus, Sheila Heti, Kathy Acker and Claire-Louise Bennett, to name a few, shows us that even Duras’ most “minor” works are worth careful consideration.

“Writing, everywhere, among all peoples, still provokes horror,” Duras wrote. But in particular the writing (and stories) of women, it seems. Male writers like Philip Roth and, more recently, Karl Ove Knausgaard have made good money off unbridled sexuality and the most revealing of personal stories, to the horror of their loved ones. But there is the sense of something jarring, even violent, when women write. “A feminine text cannot fail to be more than subversive,” Cixous wrote. “It is volcanic; as it is written it brings about an upheaval of the old crust, carrier of masculine investments; there’s no other way.”

Ernaux’s mother destroyed all of her diaries. “She did it so that my husband would never read them,” Ernaux told the New Yorker’s Alexandra Schwartz during a recent interview. Defending the frank sexuality and personal focus of her books, Ernaux has written: “I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled. There is no such thing as a lesser truth.”

Writing that truth for Ernaux and Duras is a way of bringing it into existence. “From the most ancient times, silence has been the attribute of women,” Duras wrote. “So literature is women too. Whether it speaks of them or they actually write it, it’s them.”

In ‘Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker,’ Jason McBride follows a writer who was easy to romanticize, hard to read, impossible to know.

Francine, in “The Easy Life,” reflects on her life thus far: “a fruit I must have eaten some of without tasting it, without realizing it, distractedly. I am not responsible for this age or for this image.” Thanks to Duras and Ernaux — their influence and their success — we are all tasting the fruit.

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.