Review: Plenty of novels moralize about books saving your life. This one treats them like a drug

- Share via

On the Shelf

Checkout 19

By Claire-Louise Bennett

Riverhead: 288 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Books about books tend toward the sappy. They often make the reductive, moralizing case that reading is a form of salvation, a surefire route to empathy. It is a unique pleasure to read a novel of bibliophilia that eschews this mode entirely.

For the unnamed narrator at the center of Claire-Louise Bennett’s wildly imaginative, unabashedly odd and mordantly funny second novel, “Checkout 19,” books are life itself: essential as water, ordinary as wallpaper. But reading them won’t save the world.

Growing up in a working-class family in southwest England, the narrator ingests stories like air, reveling in their particularity but also in the sensation of a soothing cycle: “Turning the pages. Turning the pages. When we turn the page we are born again,” writes Bennett. “Living and dying and living and dying and living and dying. Again, and again. And really that’s the way it ought to be.”

The narrator reads obsessively, promiscuously, everything from Aristotle to Danielle Steel. In childhood, she obsesses over even the minor, incidental qualities of books, like the fact that Roald Dahl’s author photo in the back of her mother’s hidden copy of “Switch Bitch” is different from the one in her own copy of “Danny the Champion of the World.”

Books replace other pursuits; they are their own transgression. As a young woman, when she should have been reading from the school summer reading list, she “laid down upon one of the sun loungers in a halterneck black bikini with a packet of Dunhill cigarettes and read ‘A Start in Life’ by Alan Sillitoe instead.” At the Glastonbury Festival she buys Iris Murdoch’s “The Sea, the Sea” and reads it “lying down in the top field with a paper cup of chai tea and a packet of Jaffa Cakes.”

The narrator isn’t lonely, exactly, but, like “Pond,” Bennett’s rich, strange 2015 debut, “Checkout 19” is a record of solitude. Both books are largely plotless, committed instead to describing atmosphere, physical spaces and (sometimes grotesque) embodied experience in delightfully idiosyncratic language.

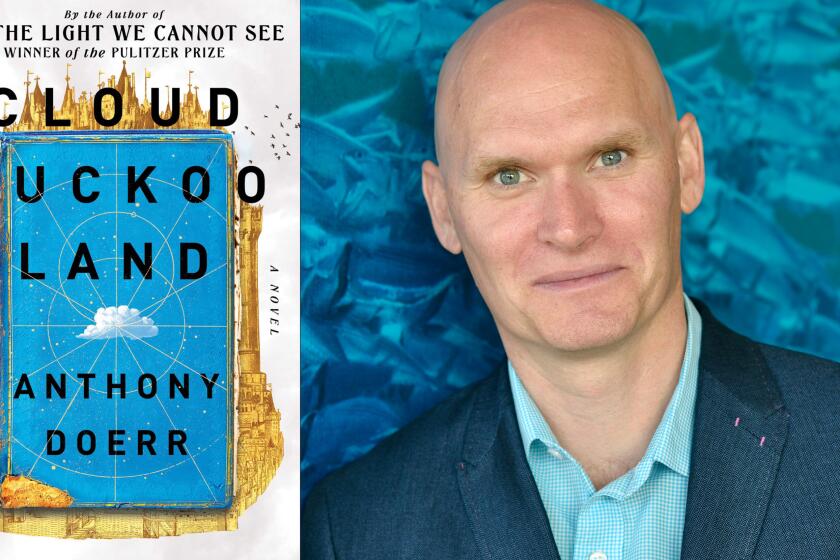

‘Cloud Cuckoo Land,’ Doerr’s followup to ‘All the Light We Cannot See,’ ambitiously maps a world connected by stories — if we know how to read them.

The title of “Checkout 19” is taken from the narrator’s weekend job as a supermarket checkout girl, where a Russian customer with a staring problem foists a copy of Nietzsche’s “Beyond Good and Evil” on her while she stands at the till.

A more compelling relationship is drawn from the narrator’s bond with Mr. Burton, a teacher who takes an early interest in her writing; she brings him a new story every week. “I gave him the stories on a Friday so they were in his home for three nights and two days,” she says. “Lying there somewhere in his house. Absorbing this environment that I could never go to. His Saturdays. His Sundays.”

The pieces she gives him are just “little things,” but their content is not important. It’s the act of letting the teacher into her mind, of passing text to a new reader, that imparts a thrill. The narrator, now deep into adulthood, feels “an urge to recall this moment” every few years. “Not only to recall it, but to write it down, again. Again.” The scene carries an erotic charge, but its intimacy really comes from the narrator laying bare her philosophy of living, an iterative — if directionless — performance with words.

Somehow nestled within this book is also a story about a character called Tarquin Superbus, “nearly always swathed in a cape or a cloak” but hard to locate in time and space (maybe he’s from the Renaissance, possibly the 19th century, Venice or Vienna, who really knows). He acquires a library’s worth of books that turn out to be blank, except for one containing a single, all-important sentence. Unfortunately, the sentence keeps disappearing.

I prepared to be irked by this swerve into the ultra-weird. But even in its surreality, this foray, like many in the novel, achieves a startling verisimilitude, as Bennett shares not just the story of Superbus but how she arrived at it. “This is how it feels inside my mind,” I ended up thinking.

Because even the tale of Superbus is a retelling, a recollection of the narrator’s attempts to write fiction in her early 20s. She returns to E.M. Forster’s “A Room With a View” after 20 years to “get right back to the beginning of myself” but misremembers a detail of that famous book. She also admits (as few die-hard readers will) that she has forgotten many of the books she’s read. (“Easy come, easy go,” I thought, a line the narrator’s father often delivered “with that soupçon of chipper sarcasm that typically permeates the many pithy observations of the proletariat.”) Still, the books have left behind a trace.

Sheila Heti’s ‘Pure Colour’ is a strange, plotless allegory — and weirdly more real than so much conventional fiction in today’s burning world.

In “Checkout 19,” reading is what gives life meaning but also possibly what adds to its meaninglessness; the violet underlining in the narrator’s copy of Paul Bowles’ “Let It Come Down” is so important to her that she feels it is wasted on the unappreciative bartender to whom she lends the book, but she has an instinctive sense of the futility in making these markings when neither the books nor the humans are permanent.

It’s not easy to read a book like this, to surf the choppy waters of sometimes disparate associations accumulated over a lifetime, to return to the same pieces of a story (the Russian, for example, reappears) but never arrive at any resolution in the usual sense of the word.

But this is not a novel that purports to offer anything like the usual satisfactions. Each thought opens onto a reference or set of associations drawn from another work. The reader is simply along for the ride. A pile of shoes? The death camps in World War II. Menstruation? The First World War. (Many things make the narrator think of the First World War.)

Fortunately, Bennett is very funny. In a middle school bathroom with her period, the narrator thinks, “Perhaps I am a nun in the north of Italy rinsing out skeins and skeins of bandages and outside in the woods tired filthy men are advancing and shooting at one another from behind dripping trees and they shall all be halted in their deplorable tracks the moment they hear me sing.”

For the true-blue reader, this book-full-of-books is a gift and proof of a rare talent. It’s not meant to be plucked from the nightstand and chipped away at over the course of weeks, but a volume to be consumed whole, on one long, strange trip.

To Bennett’s great credit, “Checkout 19” doesn’t dramatize the life-saving role of books. Reading here is not embraced as mere escape, nor glorified as edification. Bennett is not selling anything or arguing a point. In the telling of a life lived through books, and in her own sometimes floridly erudite sentences, the deep magic of writing is revealed.

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

Aron is the author of “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.