Joan Didion, ‘Goodbye to All That’ and the struggle to see yourself clearly

- Share via

Anyone who’s completed the climb out of their early twenties hopefully has the wits to remember when life was as vivid as Kodachrome and the experience to recognize that perhaps all those new colors were duller than they seemed. Perspective, after all, is one of the great pleasures of getting older. But at the date of her death Thursday at the age of 87, Joan Didion’s 1967 essay “Goodbye to All That” remains the permanent sunspot obscuring the center-vision of many maturing writers even contemplating leaving a place like New York and telling other people about it. Only a great artist creates and ruins a genre at the same time. For millennial writers who grew into the body of essays, novels and literary journalism Didion already had waiting for them, it was like sitting down to grainy footage of a party that ended long before they would ever arrive.

Re-reading “Goodbye to All That” today — in the era of online, shortform oversharing — it’s striking to a contemporary reader how those 1967 sentences trail on and curl over themselves, like smoke lifting off a cigarette in a breezeless room. “When I first saw New York I was twenty, and it was summertime, and I got off a DC-7 at the old Idlewild temporary terminal in a new dress which had seemed very smart in Sacramento but seemed less smart already, even in the old Idlewild temporary terminal, and the warm air smelled of mildew and some instinct, programmed by all the movies I had ever seen and all the songs I had ever sung and all the stories I had ever read about New York, informed me that it would never quite be the same again,” Didion writes in an opening sentence of the piece. “In fact it never was.” That first sentence has six commas and six ands. It then lands with the kind of five-word Didionism that marked her career’s dehumidified approach to writing and evaluating her own experiences.

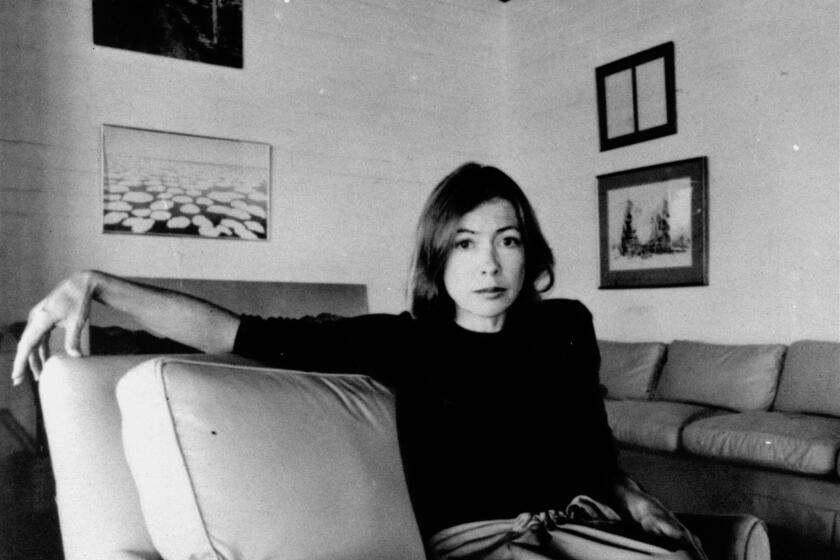

Didion bridged the world of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

A certain degree of ruthlessness with yourself conveys honesty, and it’s true that some naivete comes with being young. But not everybody might be so hard on themselves when it comes time to take stock of getting older. “Was anyone ever so young?” Didion wonders, recalling how she was afraid to call a hotel front desk to turn down the air conditioning when she was frigid, feverish and alone. “I am here to tell you that someone was. All I could do during those three days was talk long-distance to the boy I already knew I would never marry in the spring.” A husband shows up, along with some furniture, after Didion film-dissolves through a couple pages of life in minimally furnished apartments and all-night parties with strange piano salesmen and various failed writers and self-promoters of her acquaintance.

The essay is so classically a New York story, a journal entry about an outlander’s temporary harmonic alignment with a place that most Americans only recognize from their televisions. But the most universal appeal of “Goodbye to All That” is less about New York than its depiction of youth itself, the only city we’ve all lived in. “I had a friend who could not sleep, and he knew a few other people who had the same trouble, and we would watch the sky lighten and have a last drink with no ice and then go home in the early morning light, when the streets were clean and wet (had it rained in the night? we never knew) and the few cruising taxis still had their headlights on and the only color was the red and green of traffic signals.” Think about the last time you really admired the violence of how a stoplight red looks against wet pavement on an empty street. After a while, you realize that’s just how the world looks when you’re alone.

Joan Didion continues to resonate in California, even with a generation nothing like her.

Looking back, Didion seems frustrated that she couldn’t see herself clearly, couldn’t more sharply perceive at the time that being wowed has a natural expiration date that was rapidly approaching. “You see I was in a curious position in New York: it never occurred to me that I was living a real life there,” she writes. “In my imagination I was always there for just another few months, just until Christmas or Easter or the first warm day in May.” She stayed eight years.

Eventually she got tired. Many do. Finally, Didion left for Los Angeles, where the essay wraps up so suddenly that the white space arrives with the stopping power you’d meet in an electric fence. “The golden rhythm was broken,” she shrugs. After her essay appeared in the Saturday Evening Post and her book “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Didion went on to have a distinguished career, which included a lot of formidable books, including 2005’s classic “The Year of Magical Thinking,” a painful memoir about grieving the sudden death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. “It was in fact the ordinary nature of everything preceding the event that prevented me from truly believing it had happened, absorbing it, incorporating it, getting past it,” she writes of his death. Almost 40 years later, there she was, still struggling to perceive herself clearly, while offering herself to readers to be seen.

It takes time to see clearly after a departure. She knew that.

The celebrated prose stylist, novelist and screenwriter who chronicled American culture and consciousness died Dec. 23 at 87.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.