Column: Joan Didion, California and the enduring power of ‘our special history’

- Share via

The assignment I give my Orange Coast College literary journalism students every semester after our first class is always the same: Read six classics of narrative nonfiction, and write one-page summaries on each.

I send them the expected (Tom Wolfe on Southern California kustom kulture in the 1960s, Gay Talese on an aging Joe DiMaggio) and the not — if you haven’t yet read Alice Walker searching for the grave of then-forgotten Black novelist Zora Neale Hurston for Ms. magazine, then you don’t know what great writing is.

And I assign my class the grand dame of California letters, Joan Didion.

She’s everything they’re not: Privileged. Pedigreed. Possessor of polished prose. I tell my students none of this when I email them the link to “Trouble in Lakewood,” the 1993 New Yorker essay Didion wrote about the quintessential Southern California suburb, and how life there was far darker than its residents would have the world believe.

It’s my favorite Didion piece, because it captured a moment in time when suburbanites were realizing that Southern California was no longer theirs, and were not happy about it at all. I remain in awe of her meticulous unmasking of polite society, her magisterial scope of California history, her prescient inclusion of the anti-immigrant politics that went on to dictate the state’s political life through the rest of the 1990s.

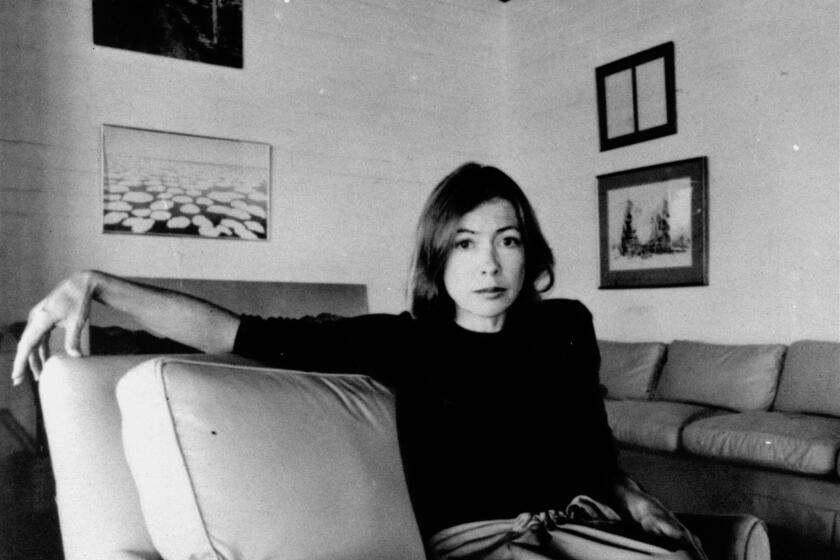

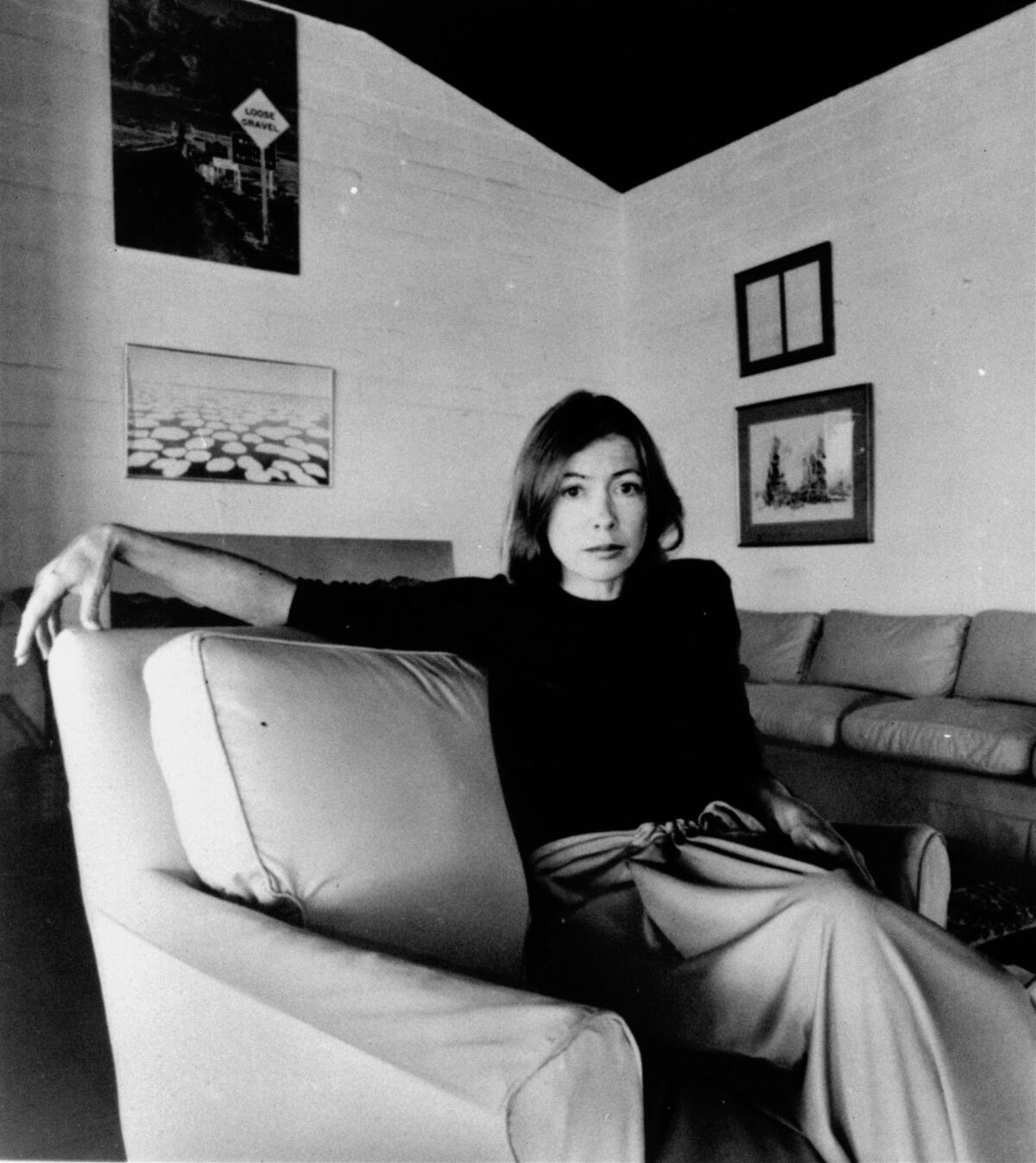

Didion bridged the world of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

Few of my students — almost all either children of immigrants or working-class — have ever heard of the New Yorker, though, let alone read Didion. Every semester, I wonder if it’s maybe better if I update my list of canonical works and leave her off. And yet every semester I’ve taught at Orange Coast College, it’s “Trouble in Lakewood” that my classes inevitably rave about the most.

I tell my students to argue in their one-page reaction paper why each piece they read is considered a classic of literary journalism. The answers for “Trouble in Lakewood” are always the same. My students enjoy her sparse, precise words and her macro-analysis of a micro-story.

They recognize the hypocritical suburbanites that Didion excoriates. The older students in my class remember the Spur Posse, the infamous gang of high school boys who scored each other on their sexual misdeeds that’s the centerpiece of Didion’s essay; the younger ones recoil in disgust that Spur Posse members were basically able to get away with their perversity, and admire Didion for going after them and their apologists.

That my students so quickly get why Didion was important speaks to the writer’s legacy.

But I assign Didion not just because of her brilliance, but to also show my students how our concept of what a journalist is supposed to be has changed. She had an insight into California and the human condition that transcends race and class, but it’s one different from how we see it today.

The celebrated prose stylist, novelist and screenwriter who chronicled American culture and consciousness died Dec. 23 at 87.

I briefly lecture on Didion in our second class, after students turn in their assignments. I share that she was a part of the so-called New Journalism, a literary movement that made celebrities out of outsized chroniclers who loved to dive into all corners of societies and emerge with rollicking stories. I also connect her to prophetic California doomsayers such as Carey McWilliams, Mike Davis and Frank Norris, who saw something rotten at the heart of the California dream.

But I also point out that Didion is starting to fall out of favor with the California writers of color of my generation, who see in her an incredible talent who really did nothing with it to improve her home state.

Her solution to what ailed California wasn’t to take to the streets, but to withdraw into her estate, or jet off to Latin America, where Didion always seemed to sympathize far more with “people power” than she did in the Golden State. What’s telling about Didion as much as what she wrote about is what she didn’t address. She went on at length about the Manson murders but offered nothing on pioneering Los Angeles Times columnist Rubén Salazar, whom Hunter S. Thompson memorably wrote about for Rolling Stone. She left it to her husband, John Gregory Dunne, to write about Cesar Chavez, while she busied herself with ennui and John Wayne.

She famously wrote: “What makes Iago evil? some people ask. I never ask.” So I share with my pupils how that approach isn’t good enough for today’s California — and that people get upset if you say that. A Latina writer friend of mine once stated on social media that she didn’t “get” Didion, and got whitesplained incessantly for it, as if she were a dolt for not grasping Didion. Writer Myriam Gurba faced a fierce backlash last year for an essay tellingly titled “It’s Time to Take California Back From Joan Didion,” all because Gurba blasted California’s intellectual guardians for allowing Didion to take up so much space at the expense of other writers, even today.

The author, who died Thursday, produced decades’ worth of memorable work. Here’s our guide to starting — or continuing — your Didion journey.

That’s why after I teach Didion in that first assignment, I move on to other writers. But I nevertheless teach her — and specifically “Trouble in Lakewood” — because I want my students to see that even someone like Didion, so unlike them, can still offer a valuable lesson to Californians of all backgrounds today.

My favorite passage in the essay is when Didion — a fifth-generation Californian whose ancestors left the Donner-Reed Party before that group suffered their grisly demise — dismisses Lakewood as a ’burb of domestic dilettantes ruining a hard-fought paradise. “Places like Lakewood did not exist before the new people came,” she wrote. “Places like Lakewood could be seen, by people like my grandfather, as the wrong side of the California dream.”

Photos from the life of Joan Didion, who chronicled California, politics and sorrow in ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ and ‘Year of Magical Thinking.’

Even though Didion wasn’t a radical, that critique resonates with my students, all strivers and dreamers like all community college students are. They know, like Didion, that the good times can disappear instantly. They know that California belongs not to those who quit it at the first inconvenience, but those who stay for all the booms and busts.

I imagine my students, heady on Didion’s words, nodding in approval as Didion blasts Lakewooders and their ilk. “New people,” she continued, “remained ignorant of our special history, insensible to the hardships endured to make it, blind not only to the dangers the place still presented but to the shared responsibilities its continued habitation demanded.”

My students might be newcomers to her work, but not the state. They’re as much a part of Didion’s Californians as professional writers like myself, all of us slouching toward whatever our future may be.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.