Review: Oscar Wilde’s life was a tragic work of art. A new biography sketches it perfectly

- Share via

On the Shelf

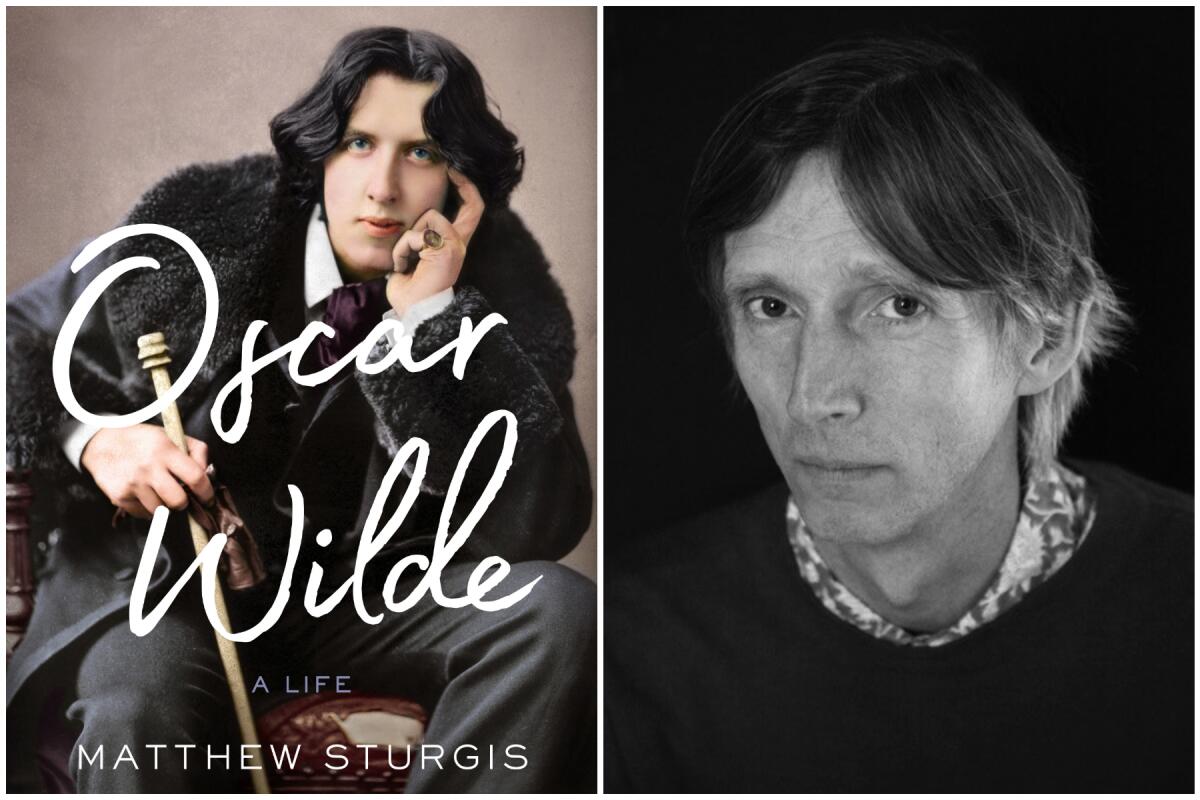

Oscar Wilde: A Life

By Matthew Sturgis

Knopf: 864 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

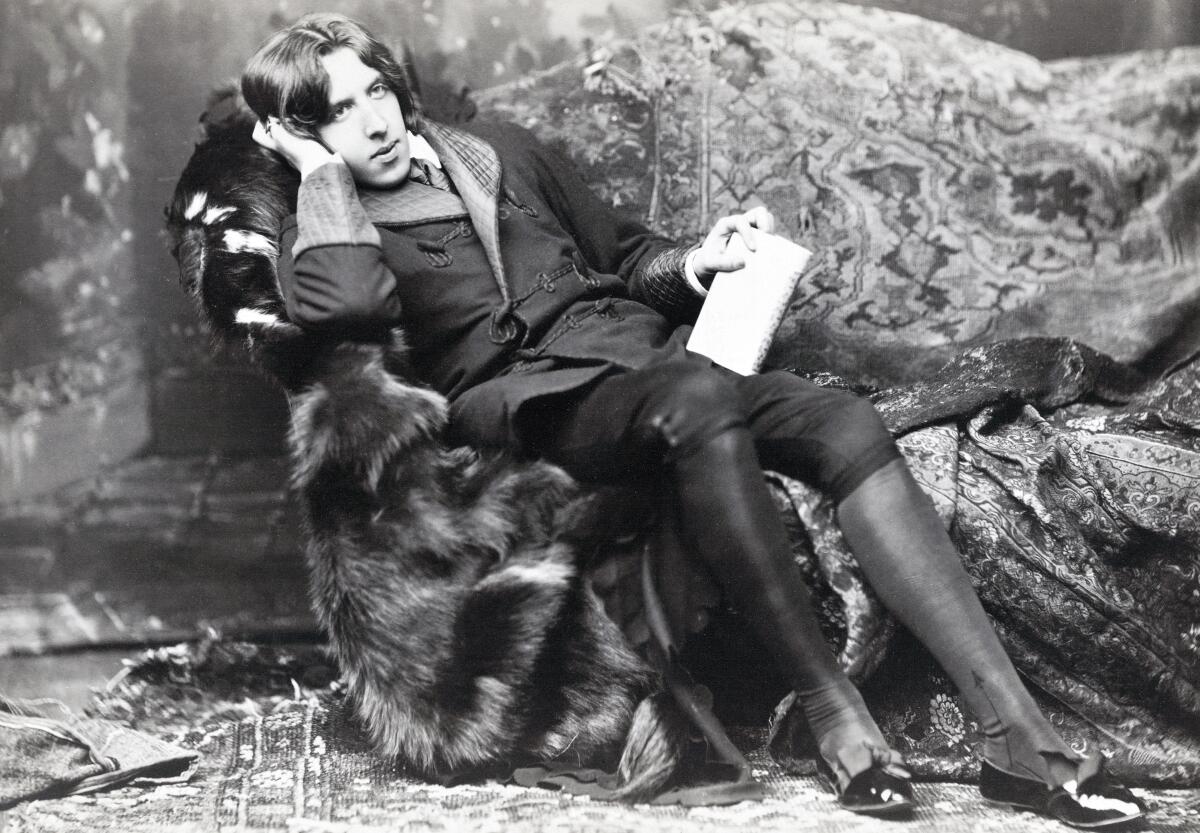

Oscar Wilde’s life reads almost like a perfectly formed work of art — one in which each early success bristles with portents of tragedy to come. Long before Wilde’s infamous libel case, his father sued the family’s nanny for claiming he drugged and molested her. As a student at Oxford, Wilde was attracted by the idealized homoerotic images of Greek culture, which led him to an increasingly unashamed presentation of himself as a man who adored (and was often adored by) younger men. And after confessing early that his main aims in life were “success; fame or even notoriety,” he lived to achieve all three. As a prominent London spiritualist told him before his first libel trial: “I see a very brilliant life for you up to a certain point. Then I see a wall. Beyond the wall I see nothing.”

Even though many books have been written about Wilde, he continues to attract good scholars. Matthew Sturgis’ new book, “Oscar Wilde: A Life,” the first major biography since Richard Ellmann’s in 1987, provides an excellent opportunity to revisit and re-enjoy the fabulous genius of Wilde.

While Sturgis doesn’t approach his subject with Ellmann’s critical intensity, he includes much new material, especially recovered testimonies from Wilde’s reputation-ending trials in 1895. The first two-thirds is as bright and entertaining as an evening with its subject; the final third describes one of the saddest stories ever told.

For the record:

10:43 a.m. Oct. 19, 2021An earlier version of this review said one of Sturgis’ previous biography subjects was Algernon Swinburne. It was Walter Sickert.

The author of biographies of Walter Sickert and Aubrey Beardsley, Sturgis writes knowledgeably about Britain’s “Decadent Nineties,” when a growing circle of talented, revolutionary writers and artists prowled the streets of Soho and Mayfair. Their work was lush, decorative, bizarre and sometimes obscene, laying bare the hidden indulgences of what Steven Marcus has called the “secret” Victorians. For while the beau monde of Wilde’s day might have appeared to be polite, Dr. Jekyll-like ladies and gentlemen in their well-lit drawing rooms and cafes, at night they could be found roaming the foggy alleys of licentious London like the gnarly, insatiable Mr. Hyde. Sturgis captures both the age and the man in all their contradictory light and darkness.

Veteran biographer A.N. Wilson takes on one of the most popular, prolific and puzzling writers in English literature in “The Mystery of Charles Dickens.”

Wilde didn’t create the “aesthete” generation, but he adopted its mannerisms so adroitly that he soon exemplified it. An avid “networker” from his earliest days at Oxford, Wilde gravitated immediately into the orbits of his two most illustrious Oxford professors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin, and was soon eagerly introducing himself to Lillie Langtry and Ellen Terry, the most glamorous stage actresses of his day.

When popular lampoons of the “aesthetes” began appearing as cartoons in Punch or as musicals on the West End stage, Wilde hurriedly claimed credit for them — whether they were based on him or not. When a story went round that he paraded down Piccadilly with a lily in his hand, Wilde remarked, “Anyone could have done that.” Instead he had achieved “the great and difficult thing” of making the “world believe” he had done it.

“Nothing succeeds like excess,” Wilde famously said, but then Wilde famously said a lot of things; it’s hard to think of any artist who has been more frequently and happily quoted. His first great literary invention was himself. Surprisingly, his breakthrough “literary” success was as a public speaker; in the early 1880s, during a lecture circuit from New York to San Francisco and back, he “conquered” America as utterly as the Beatles would 70 years later. And he never missed an opportunity to meet anyone whose name could be dropped at the next social event — Walt Whitman, Louisa May Alcott, Ulysses S. Grant, Jefferson Davis. In many ways, he must have been a welcome antithesis to high-toned, somber intellectuals like Henry James and William Dean Howells; he was more a precursor to the 20th century’s stadium-filling stand-up comics, such as George Carlin and Steve Martin.

Wilde’s gift for producing beautiful sentences and self-mocking comic observations indicated deeper talents than mere wordplay. After trying his hand at various unsuccessful careers — editor, historical dramatist, husband — he gathered up the clever remarks of his youth and replanted them in some of the greatest prose of his generation: essays, short stories, some elegant poetry and one poetically elegant play (“Salome”). Then, in the 1890s, the great audience-pleasing stage comedies came roaring along, from “An Ideal Husband” to “The Importance of Being Earnest,” in which he pioneered yet another American genre, the “screwball comedy.”

Yet his greatest single work, and the one least appreciated in Wilde’s lifetime, was probably “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” which today reads like another intimation of Wilde’s doom. This short, perfectly written little novel presents all the disparate sides of Wilde’s complex personality — from the gloriously self-aggrandizing Oscar who graced parties, theater balconies and lecture stages to the secretive one who obsessively indulged himself. As Wilde wrote about the book’s three major characters: “Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry is what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be — in other ages, perhaps.”

Reading Woolf’s extended essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ is a transformative moment for one 15-year-old Tucson girl.

Eventually, the portents gathered steam and, at the height of Wilde’s fame, knocked him down so hard he never got up again. After his relationship with the wayward Lord Alfred Douglas and several other young men became known, Douglas’ father, the Marquess of Queensberry, left a card for Wilde at the Albemarle Club accusing him of being a “ponce” and a “Somdomite [sic].” Though Wilde was entreated by friends to take the quiet road away from controversy, as usual he chose the performative one. He sued Queensberry for libel, gave one of his funniest and most moving public presentations in court, and lost. Queensberry responded by filing criminal charges for “acts of gross indecency with other male persons.”

For a man who was often generous and kind — and just as often deeply arrogant and selfish — Wilde suffered one of the saddest public downfalls in modern times. Sturgis’ account of his final years is more convincingly detailed than in any other biography. Several days of testimony recounted stains on hotel bedsheets and details of Wilde’s sexual predilections; Wilde was eventually sentenced to two years in prison, where he was reduced to sewing mail bags and consulting with the medical staff on his frequency of masturbation. Life grew so dire that friends and family were concerned he might kill himself. (Some even thought it a good idea.) But as Wilde said: “I know it’s the only way out, but I haven’t the courage.”

After Wilde was released, he fled to Italy and France and lost everything he loved. His mother died in 1896, his estranged wife Constance two years later. Wilde himself died painfully from meningitis at 46. Except for “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” he completed hardly anything after his downfall, mainly because, as he confided to friends, he found it impossible to “laugh at life” anymore. Amid all the darkness of Sturgis’ closing chapters, those words are easily the darkest.

As Pissarro commented when the British press nailed shut the coffin of Wilde’s reputation, Victorian society didn’t hate Wilde for his homosexuality so much as for his art. And nobody ever personified the graceful and beauteous indulgences of art better than Oscar Wilde.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

Bradfield is the author of “The History of Luminous Motion” and “Dazzle Resplendent.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.