A blind horse, a beaten-down musician and a journey out of despair

- Share via

Book Review

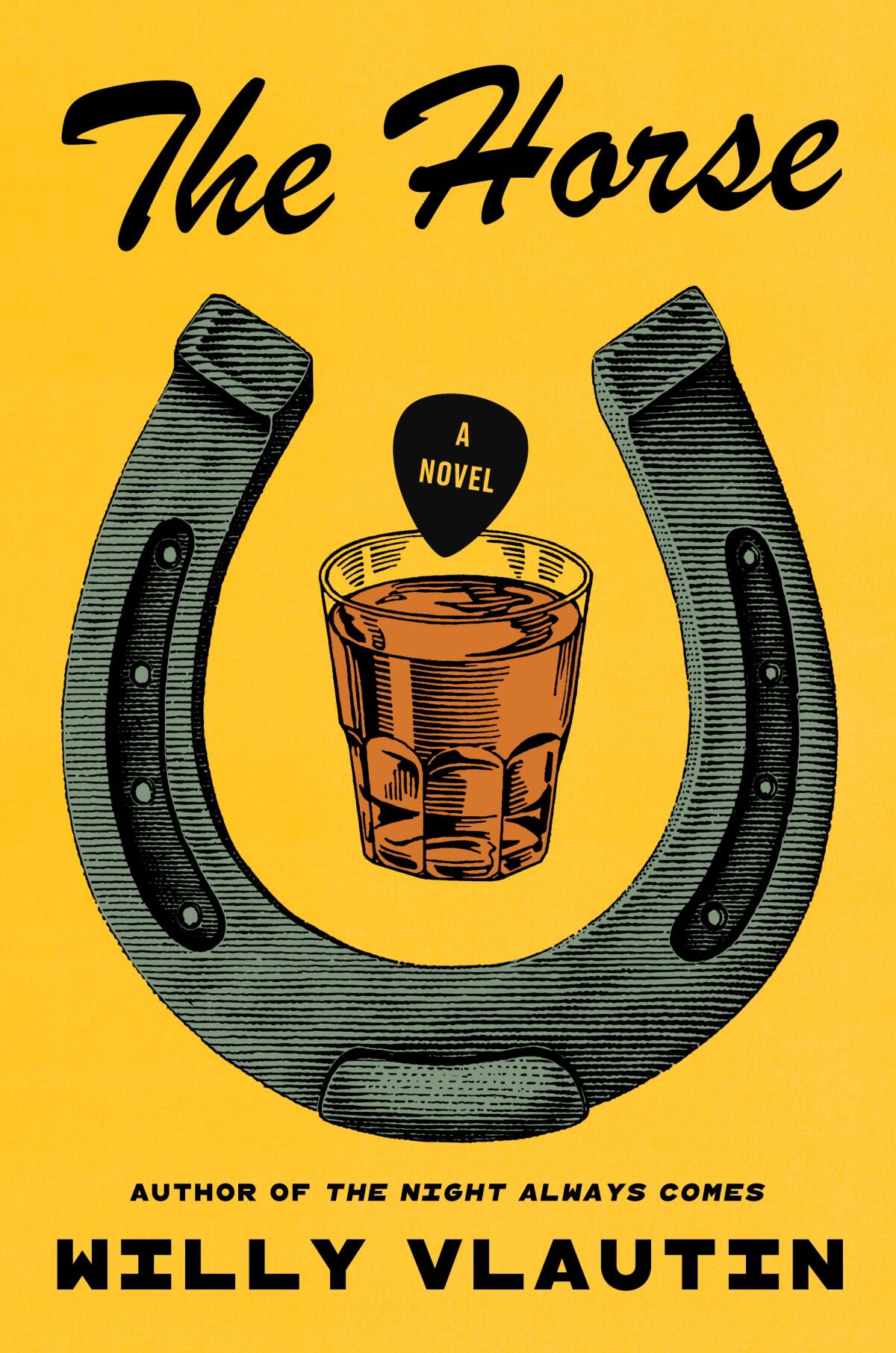

The Horse: A Novel

By Willy Vlautin

Harper: 208 pages, $25.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Willy Vlautin has a soft spot for horses.

In his six previous novels, horses show up again and again in anecdotes, as transportation and even as characters. Vlautin’s third novel, “Lean on Pete,” is about a boy who works at a dilapidated race track in Oregon and befriends a racehorse destined for the glue factory.

Horses also appear with regularity in Vlautin’s songs. He has released several albums, EPs and singles as a solo artist and with his bands Richmond Fontaine and, more recently, the Delines. In 2016, Richmond Fontaine released the album “You Can’t Go Back If There’s Nothing to Go Back To,” which featured the song “The Blind Horse.” It’s an instrumental, as if Vlautin didn’t have the words to describe what it must feel like to be so agonizingly lost in the wilderness of the American West.

With the publication of his latest novel, “The Horse,” Vlautin announces he has plenty to say about such a predicament, and it just might be his masterpiece.

The novel opens in the early 21st century with a blind horse stumbling into an old deserted mining camp in central Nevada where Al Ward has settled down to die. Al is a musician and an alcoholic who is so disgusted with himself and the shambles he has made of his life that he has retreated to a remote redoubt where he can’t cause harm to anyone but himself.

Al spends his days in a single-room shack, lighting his wood stove, making coffee and heating up cans of Campbell’s soup, just barely doing enough to survive. As he fetches firewood and goes on his daily walk, his mind wanders and his thoughts drift to the bands he used to play in, the women he loved and lost, and the songs he wrote along the way.

Al still has a guitar and a spiral-bound notebook in which he composes sad, soulful ballads. These songs are more than a record of the places he went and the people he met; they are an affirmation of the one thing that gave his life meaning. When he thinks back to playing with his bandmates, in those moments “suddenly Al wasn’t Al anymore,” Vlautin writes. “He was transported inside the noise and rhythm and melody and story. It was as though suddenly he understood that just by a song playing he was able to vanish from himself.”

This vanishing, however, came with a price. The relief Al sought in music only lasted as long as the show went on, and as the years piled up the tours brought in less money and took him farther from home. Even worse, the alcohol — the stuff that got him through a life on the road — turned on him.

“He didn’t remember falling or scraping his hands or the sound of the guitar breaking. He remembered only waking up in his car outside the Banc Club covered in vomit, his guitar in pieces, and his notebook gone. For over forty years of drinking, he’d seldom blacked out, but now he frequently did.”

Unable to drink like he used to, Al retreats to the deserted mining camp, where his memories take on a spectral presence.

Then the horse shows up, shocking Al back to life and into action, but he’s been lost inside himself for so long, he’s not even sure whether the horse is real.

Unlike many of the cowboys and ranch hands that Al sang about and Vlautin writes about in his books, Al isn’t equipped to help the animal.

“Al knew nothing of horses. Never once had he ridden one, and he couldn’t remember ever having touched one. As a kid he had never gone to camp or to somebody’s ranch. He couldn’t recall having even seen one up close.”

More comfortable in a casino in Reno than a shack 50 miles from the nearest town, Al realizes that if he is going to save this horse, he has to do something he was never able to do for himself: ask for help.

Vlautin writes about the “sickness and regret, sorrow and self-hatred” endemic to addiction in a way that is both shattering and tender. This is familiar territory for Vlautin, who was born and raised in Reno, and has spent the better part of his life writing and singing about people at the fringes of society, but “The Horse” marks the first time he’s written from the perspective of a musician.

The book is dedicated to L.A. singer-songwriter John Doe, most famously of the punk band X. Al’s memories of playing in a punk band with the Sanchez Brothers, who are infamous for getting in fights with each other, paint a picture of what can happen to those who were born to go too hard, too fast.

Throughout the book, Al recollects the titles of the songs he’s written for the bands he played in and the women he loved, and these catalogs of song titles serve as a secret text that runs through the novel. The songs he wrote for the Sanchez Brothers, “Uno, Dos, Tres — I’m Gonna Bust Your Face,” are especially spirited, but the number of songs referencing his ex-wife Maxine speak to the depth of his despair in a way that the lyrics never could.

Vlautin’s gift for capturing the unique terror of the moment when heavy drinking turns to helplessness is rendered with heartbreaking acuity. Set against the desolate majesty of the high desert, Vlautin’s depiction of one broken soul trying to save another is aspirational, allegorical and, ultimately, transcendent. If a heavy-hearted road dog like Al can lift himself out of his malaise to help a wayward old horse, maybe there’s hope for him — and the rest of us — after all.

Jim Ruland is the author of the novel “Make It Stop” and the narrative history “Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.