Deaths from drug overdoses plateaued in L.A. County in 2023 after years of increases

- Share via

Deaths from drug overdoses and poisoning reached a plateau last year in Los Angeles County — the first time in a decade that such fatalities had not continued a year-over-year rise, public health officials said.

Across L.A. County, 3,092 lives were lost to drug overdoses or poisoning in 2023, a slight decline from 3,220 deaths the year before, according to a newly updated report. County officials welcomed the change after years of devastating increases in overdose deaths but said much work remains to be done to save lives.

Dr. Gary Tsai, director of the substance abuse prevention and control division at the L.A. County Department of Public Health, said that as the county has pushed to expand treatment, prevention and harm reduction efforts, “we’re excited to see the progress, but also recognize that it’s not a win.”

“We’re still in the worst overdose crisis in history,” Tsai said. Still, he said, the new numbers could at least disrupt the “sense of inevitability that comes with trend lines that don’t seem to ever change.”

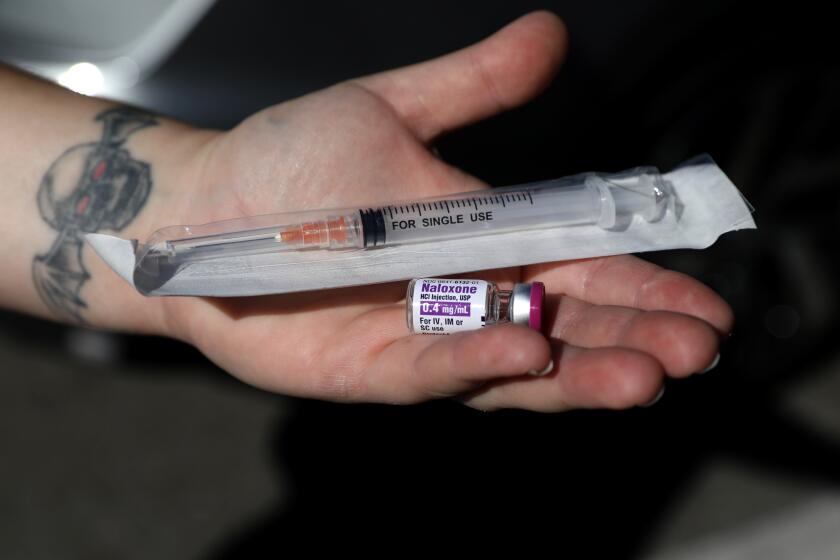

Earlier this year, L.A. County officials said they were relieved to see that the rate of deadly overdoses had stopped surging among unhoused people in 2022. Health officials credited a dramatic increase in community distribution of naloxone, a medication that can rescue people from an opioid overdose.

The flattening numbers also echo early estimates on the national level, which showed that overdose deaths had fallen slightly last year in the U.S. Experts have cautioned against declaring victory, however.

The state and L.A. County have worked hard to make Naloxone more widely available. One of the hurdles, though, has been the price of the inhalable version, Narcan.

“It’s too early to tell,” said Dr. David Goodman-Meza, an overdose researcher in L.A. County who works with Wellness Equity Alliance. “On an optimistic side, we would hope that this flattening is related to all the harm reduction activities that we’ve been undertaking” in L.A. County and nationwide, such as handing out more naloxone, as well as making it easier to access medications that help people shake off addiction.

But in the past, the U.S. has seen deadly overdoses dip one year, only to resurge. “It’s hard to know at this point if we’re in the eye of the storm,” Goodman-Meza said.

As drug-related deaths have slowed nationally, health researchers have also raised the grim possibility that fentanyl has had such a devastating effect that there are fewer people remaining to be killed.

Fentanyl and methamphetamine have both played a fatal role in drug deaths in L.A. County, with many overdoses involving a mixture of drugs. The updated analysis from the L.A. County Department of Public Health focused specifically on the toll of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that has caused a skyrocketing number of deaths in the county — rising from 109 to 1,970 fatalities between 2016 and 2023.

Shoshanna Scholar focuses on practical strategies for reducing the negative effects of drug use and addressing it as a health issue rather than a criminal one.

Among the other findings:

- Death rates from fentanyl dropped for young adults ages 18 to 25 for the second year in a row but continued rising for other age groups, particularly adults ages 26 to 39. Tsai said one possible reason is that for younger people, it may be easier to avoid risky decisions before they have started using drugs regularly. “For them, the decision may be, ‘OK, there’s this bowl of pills at this party I’m at — I’m not going to do it,’” Tsai said. “It’s easier to hold back on that than someone who’s been using methamphetamine for the past 20 years trying to avoid fentanyl-tainted drugs.”

- There is a growing gap in the mortality rate from fentanyl overdoses between Black and white residents: The death rate from fentanyl continued to grow for Black residents of L.A. County, hitting a point roughly twice as high as that among white residents, whose mortality rate from fentanyl fell slightly last year. “We’re beginning to sort of bend the curve in the right way on overdose deaths, but not for everybody,” said Ricky Bluthenthal, a professor of population and public health sciences at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. Harm reduction has had “a historic challenge in consistently reaching Black communities,” he said. In the past, Bluthenthal and fellow researchers found that in L.A. and San Francisco, Black and Latino people were less likely to have received naloxone than white people. In light of the widening gap, he said, the question in L.A. County should be, “What can we be doing different that’s going to make sure that Black folks who are using fentanyl have naloxone readily available to them?”

- Latino residents also saw a rising rate of fentanyl-related deaths. Although their rate remained lower than that of white people in L.A. County, the increase drove the number of Latinos in L.A. County who died from fentanyl above the number of white residents killed by fentanyl for the first time, public health officials said.

- Although fentanyl has taken lives in rich neighborhoods and poor ones, the death rate from fentanyl was at least twice as high in the poorest areas of L.A. County than in areas with lower poverty. The rate of fentanyl deaths continued to surge in the poorest parts of the county. The report also divided L.A. County into geographic regions and found that the rate of fentanyl-related deaths has been starkest in its “Metro” region, which spans from Eastside neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights and El Sereno to West Hollywood and includes downtown L.A., Westlake and Hollywood.

California is in line for more than $4 billion in opioid settlement funds, and local governments are most often spending the first payouts on lifesaving drugs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.