- Share via

Last in a four-part series examining how Latino political power has changed Los Angeles.

PART IV: SELA UNITED

The crowd lining Pacific Boulevard in Huntington Park roared as peewee football players and cheerleaders strolled by. Middle and high school marching bands blasted Christmas classics, prompting people to yell out the names of the schools.

The cheers continued for the Huntington Park City Council, seated atop classic convertibles. Following them a few minutes later was a trolley filled with smiling council members from nearby cities.

Not too long ago, the politicians at the Huntington Park Holiday Parade would have been greeted with boos and rotten tomatoes.

For a generation, southeast Los Angeles County has been synonymous with political malfeasance. Scandal after scandal in Huntington Park, South Gate, Bell, Bell Gardens, Maywood, Commerce, Cudahy, Vernon and Lynwood made local — and sometimes national — headlines. In Bell, a 2010 Times investigation exposed massive corruption, and six city officials eventually went to prison or served home confinement.

All the political drama not only besmirched the region but also called into question the very idea of Latino political representation. Most of the corrupt officials were Latinos, representing cities whose demographics had flipped in the 1980s from overwhelmingly white to overwhelmingly Latino.

Was this what the rest of Southern California could expect, once Latino power spread?

The road to influence has been full of trials and triumphs. From the Eastside to the Valley to South L.A. to Southeast L.A. County, columnist Gustavo Arellano dives into the key moments and alliances.

This sordid past clashed with what I saw at the Huntington Park parade: small-town America at its best, with a Latino face.

Before they got on the trolley, most of the politicians — decked out in coats and their Christmas finest — groaned when I brought up the nickname coined by former Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon: the “corridor of corruption.”

“Don’t judge us by our past but by right now and our future,” said Ali Saleh, who has served on the Bell city council since 2011. Of Lebanese descent, he speaks fluent Spanish.

“We want people to believe in government again,” said Lynwood Councilmember Juan Muñoz-Guevara as Cudahy Councilmember Martin U. Fuentes laughed and said, “Yeah!”

“We’re taking tangible steps in improving,” said Bell Councilmember Monica Arroyo. “Now, we need to build it more.”

Maywood Councilmember Heber Marquez told me earlier in a phone interview that municipal corruption “seemed like the norm” when he was growing up. “I didn’t know there was better, let alone that I could be part of any possibility to make things better.”

Marquez, a former teacher, ran for office in 2018 after explaining to his students at Maywood Center for Enriched Studies how city government should run. Anti-corruption prosecutors had recently raided the business and home of Mayor Ramón Medina, who is now facing 18 felony charges.

“So my students told me, ‘You tell us you’re supposed to stand up for our community?’” Marquez, 38, said. “‘Well, run.’”

They represent a new generation of politicians: southeast L.A. County natives in their 30s and 40s who came of age during their hometowns’ worst days. They’re pushing back against the region’s doom-loop reputation by trying something new: working together.

They’ve collaborated to bring resources and power to an area long ignored by the rest of the county. Among their successes: representation on regional boards such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the South Coast Air Quality Management District. Grants that address food insecurity and homelessness. COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites in their cities, which suffered some of the highest infection rates in L.A. County.

“I think we’re headed in the right direction,” said 56-year-old Bell Mayor Fidencio Gallardo, who has served on the City Council since 2015. “I think we’re moving away from that old kind of transactional leadership. There’s still pockets of it here and there. But I still think it’s better.”

“For a while, we were like, ‘Hey, let’s collaborate,’” said Graciela Ortiz, a 43-year-old Huntington Park councilmember since 2015. “And then, when the pandemic hit, it was something that we had to do.”

On WhatsApp and email, group members — including at least one council member from every city in southeast Los Angeles County — share ideas, articles and funding opportunities. And they hang out for fun. In the last three years, they have taken turns hosting Thanksgiving and Christmas parties in their cities, branding them this last time as “SELA-giving” and “SELA-bration.”

Little of what they advocate for is “Latino,” per se — which makes what’s happening so interesting. When the area you represent is mostly Latino, what does it mean to be a “Latino” politician, anyway? And can a new generation completely escape the sins of its predecessors?

Roughly bracketed by Alameda Street, the 105 Freeway, the 5 Freeway, the Rio Hondo and Washington Boulevard, the cities of SELA (an acronym for southeast L.A.) attracted Midwesterners and Dust Bowl refugees who found affordable tract homes and well-paying blue-collar factory jobs after World War II.

Glimpses of that picket-fence past are still visible. Downtown storefronts feature old-style marquees. Street signs seem created by Hobby Lobby — Art Deco black font on a white background in Maywood, white cursive on blue in Huntington Park, white azaleas in South Gate.

But on SELA’s main thoroughfares, there are trash-strewn empty lots, shuttered factories and vacant buildings. The region is 94% Latino — nearly double Los Angeles’ 48% — with high rates of poverty and overcrowded housing, according to census data compiled by USC’s Lusk Center for Real Estate.

When Gallardo, the Bell mayor, and his parents moved to Huntington Park in the mid-1970s, they were the first Latino family on their street. Gallardo’s best friend at State Street Elementary in South Gate was white.

When the two entered middle school, the boy told Gallardo his family was moving.

“He said that his parents thought there were too many Mexicans moving into the neighborhood — and the parents didn’t like it,” Gallardo said as we sat on the steps of his alma mater, Bell High. A slogan etched above us read: “Honor Lies in Honest Toil.” He drank from a water bottle with a map of the southeast L.A. cities and the slogan “SELA Presente.”

White flight turned most SELA cities majority Latino by the 1980s, but their city councils didn’t reflect this shift. That began to change in 1991, when Bell Gardens voters recalled four white council members who tried to change zoning laws to control housing density, a move critics said was anti-immigrant. The council turned majority Latino in a special election the following year, earning national attention and allowing activists to imagine a bright future of representation.

After more than 20 years of struggle for a greater voice in Los Angeles politics, the concept of “go along to get along” simply hasn’t worked for Latinos in general--and particularly for Chicanos.

One by one, the other SELA city councils flipped to a Latino majority. Nearly everyone elected was a novice to politics. Drama descended almost immediately, starting with Bell Gardens. A mayor threw a chair at a colleague during a closed session and alleged that her opponents had tried to run her husband off the road. A council member voted on matters involving companies that had donated money to a nonprofit he ran. Recall attempts quickly bloomed.

As early as 1994, The Times described politics in the cities as “often a hubbub of conflict and scandal.” Others said it was just growing pains.

“[Latino politics in SELA] is at a nascent stage, but it will coalesce and get past the chair throwing,” a political analyst told The Times that same year. “I don’t think you can categorize these cities by allegation and indictments. This is only a snapshot in time and it will pass.”

It didn’t.

The churn of bad politicians disgusted residents like Miguel Santana, a native of the Mexican state of Jalisco. He and his wife, Ana Maria, bought a home in Bell Gardens in the early 1970s.

“At first, we felt proud” of all the new Latino leadership, he said in Spanish. We were eating lunch at the elegant La Casita Mexicana in Bell with Ana Maria and their son, Miguel A. Santana, former chief administrative officer of Los Angeles and now head of the California Community Foundation. “Then, we felt very deceived.”

I asked Miguel Sr. why he felt that way.

“Because one of our own was now there [in City Hall],” he replied. “Before, it was pure güeros. But when we started to see how [Latino politicians] behaved — right away! Ugly, gossipy campaigns.”

His son, who voted in the 1991 Bell Gardens recall elections while attending Whittier College, knows too well that a few bad Latino politicians sully the reputation of the rest. As a longtime advisor and former chief of staff to late L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina, he had an insider’s view of the rise of Latino political power in Los Angeles — and the bumps along the way.

“It is unfair that the corruption of a handful casts a shadow on us all,” Miguel A. Santana said. “Like it or not, as the region’s majority population, we [Latino leaders] have a unique duty, today more than ever, to demonstrate that we are ethical, inclusive and fiscally responsible.”

He and his peers winced at the stream of negative headlines from SELA throughout the 2000s. They complained that the media began to care about corruption only when Latinos took over. Yet political solutions seemed impossible. Factions warring within cities and between cities begat more scandals, more corruption.

After the Bell fiasco, however, major nonprofits such as the Weingart Foundation — which Miguel A. Santana once headed — and the California Community Foundation took action. They began funding community groups to transform SELA from the ground up. Grants went to nonprofits using the arts to keep children off the streets, or engaging teenagers on issues that disproportionately affected SELA, including a lack of park space and environmental racism.

Cities such as Maywood, Bell Gardens and Cudahy are trying to address the affordable housing and homelessness crises. Landlords argue rent control will result in less housing.

“SELA cities have no power, and you’re competing with the Santa Monicas of L.A.,” said Wilma Franco. She heads SELA Collaborative, a coalition of nonprofits invested in the region. The group has commissioned surveys that show the value of banding together — even something as simple as using the acronym SELA.

“To even see that being used — ‘I’m a SELA leader’ — I’m like, ‘You know, five years ago, none of you were saying that!’” Franco said.

The new generation of politicians has done a good job of uplifting and empowering the community. But she urged them not to forget their roots.

“I would hope that they keep in mind, who puts them in the position that they’re in? It’s the community.”

Elizabeth Alcantar was elected to the Cudahy City Council in 2018 at just 24. She began her political career as a field aide to L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis, organizing resident caravans to Sacramento to ask for funds to clean up the long-shuttered Exide battery plant in nearby Vernon. During her time on the council, Cudahy implemented rent control initiatives along with Maywood and Bell Gardens.

We met at Cudahy Park, where the past and future of her hometown collided. Behind us was a half-completed mural. In front of us was a derelict baseball diamond and mangy grass fields. This year, the mural will be finished, and the park will be remade with millions of dollars in state grants.

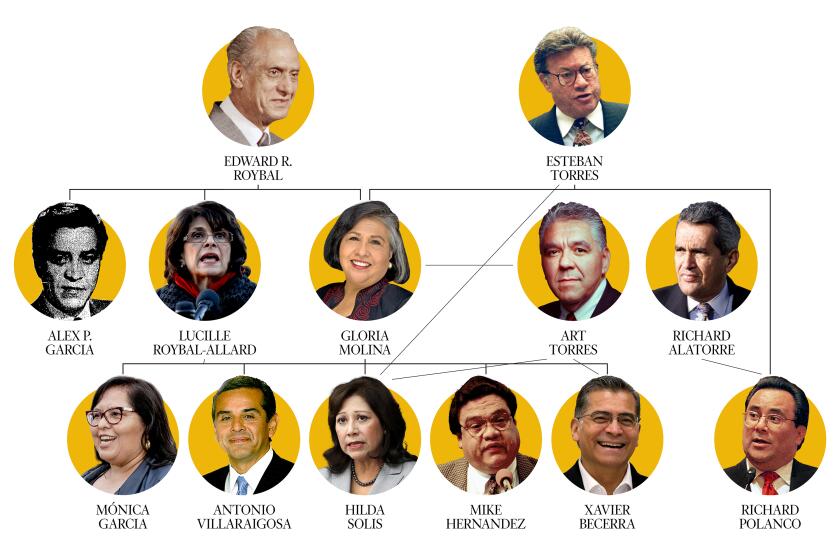

Connections among Latino politicians in Los Angeles can get confusing. We attempt to decipher the oldest political trees: the Eastside and the San Fernando Valley.

“I think folks that got elected right after [the scandals of the last decade] had a lot of weight on their shoulders of just cleaning things up,” Alcantar said. She wore a gray T-shirt that read, “Southeast L.A. vs. Everybody.” Nearby, cyclists sped up the Los Angeles River trail. “They didn’t really get to be as creative as we do.”

People who lived through SELA’s worst days are hopeful about its political youth movement.

“It should’ve happened years ago,” said Huntington Park High principal and South Gate native Carlos Garibaldi. He attended the Huntington Park holiday parade to cheer on his school’s marching band and mingle with SELA dignitaries at a small banquet. “These are people who have come from the community. They have firsthand knowledge of how it works, and they have the passion to bring it to the future.”

Becky Nicolaides, a historian who has written a book about SELA’s history, said that if the new wave continues notching successes, “that would be a game changer. It would truly be the first time that [SELA Latinos] consolidated that voice and that power. That would be huge potential for the future.”

Former Assembly Speaker Rendon, who recently secured $8 million in state grants for a Frank Gehry-designed SELA Cultural Center in South Gate, said the new generation is “smart. They’re appropriately impatient. They don’t want to hear about studies. They want solutions.”

It’s great to hear people be so boosterish about SELA, a region that needs all the positive press it can get. The media have obsessed over political corruption in immigrant and ethnic communities since the days of Tammany Hall in New York. But as I interviewed politician after politician for this story, I always remembered something Marquez, the Maywood council member, told me about the year he served as mayor, which is a rotating position in his city.

“When I introduced myself as Mayor Marquez, I saw the way people completely changed how they interacted with me,” he said. “You get this title, and it changes people. We’ve seen the cycle too many times.”

Latinos are no more predisposed to political corruption than others relatively new to power. Nor is SELA, really. But the conditions that let it fester — apathetic voters, a lack of watchdogs, candidates who put themselves first — still remain. Nonprofits supported by the likes of SELA Collaborative have bettered life for residents. But some activists still prefer to stay distanced from the electoral process.

If SELA is to truly thrive, los buenos — the righteous — need to really, truly check one another instead of just cheer one another on.

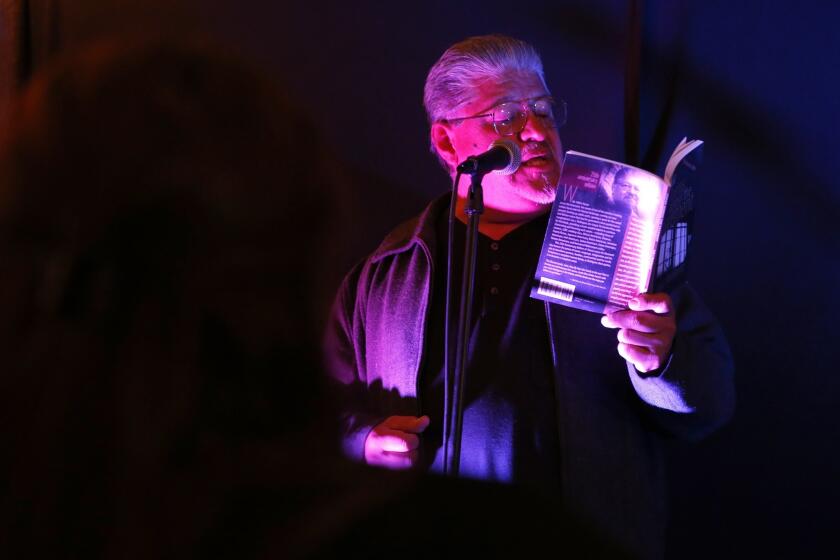

For the last three months, musicians, painters and poets throughout southeast L.A. County have traveled to Eric Contreras’ garage for an open-mic night called Alivio, the Spanish word for relief.

Hours before lunching with Rendon in Lynwood, I had breakfast up the road with Hector De La Torre in his hometown of South Gate. He was on the City Council in 2003, when three council members and Treasurer Albert T. Robles were recalled amid corruption allegations. Robles was later sentenced to 10 years in prison.

De La Torre went on to serve in the California state Assembly. He now sits on the California Air Resources Board and heads the Gateway Cities Council of Governments, which advocates for 27 cities stretching from Montebello to Long Beach to Cerritos and all the SELA cities.

Allyship with South Gate’s neighbors “was not a thing” when he was on the council. “We fought with each other for resources,” he said.

He appreciates that new politicians “want to be kind of in the mix of new things” but sees challenges ahead.

“They’re at the point where the ideological meets the practical,” De La Torre said. “They all have progressive politics. But how do you implement that at a city level? In terms of initiatives, I’m not seeing the unity that they want to practice.”

Amid the warm feelings at the Huntington Park holiday parade, there was an undercurrent of discord. Gallardo, the Bell mayor, and Ortiz, the Huntington Park council member, are running against each other for a seat on the L.A. Unified school board.

If either comes out on top of the four-person field, they would be the first school board member living in SELA.

Ortiz, an LAUSD administrator, has raised the most funds so far. She’s also grabbed more endorsements from her fellow SELA council members than Gallardo, a senior aide to the incumbent, Jackie Goldberg. At the parade, Gallardo wasn’t on the trolley with SELA officials — he said no one from Huntington Park invited him. But pacing inside the parade route, checking in to see where he could help, was 57th Assembly District candidate and longtime Huntington Park power broker Efren Martinez.

A few days before, Ortiz and I sat on lawn chairs in front of Miles Elementary School, where she was a student. Her middle school and high school were a short walk away. Next door was City Hall.

She vowed to support Gallardo if he moves on to the general election and she doesn’t, while Gallardo was noncommittal about the reverse scenario.

SELA’s corrupt legacy weighs heavily on Ortiz and her fellow politicians, she said.

“I always believe that we have to be 10 times more perfect than anybody else, because unfortunately, the media — no offense — they pin us as guilty until proven innocent. So here we are, a new set of leaders coming in. But we still have to cross our T’s, dot our I’s extra more than anyone else, because the reality is that everyone’s already looking at our region because of the past.”

The afternoon sun kept forcing the two of us to move into the shade.

“We talk about that all the time,” Ortiz concluded. “We have to make sure [we’re not corrupt], because all eyes are on us.”

I came away impressed at how candid Ortiz was, and I look forward to more innovative collaborations among SELA leaders in 2024.

But a little more than a week into the new year, the specter of scandal reemerged.

A lawsuit by an unnamed plaintiff claimed that Ortiz and Martinez, the Assembly candidate, were liable for the actions of a campaign worker, who pleaded no contest to sexual misconduct with an underage volunteer.

Ortiz denied the accusations, calling them “frivolous” and “slanderous.” Nevertheless, she was put on administrative leave from her LAUSD post while the district investigated, before being reinstated as of Feb. 27.

I found the timing of the lawsuit, less than two months before the March 5 primary, suspicious. And yet I couldn’t help wondering: Could this morph into another SELA political embarrassment? Tracing the threads to the ghosts of SELA’s sordid past was easy.

Martinez, who was Ortiz’s campaign manager in 2015 and ran unsuccessfully for City Council himself three times, sued former Huntington Park Councilmember Linda Guevara twice in 2021. He alleged that she defamed him and had violated his civil rights by writing on social media that he should be investigated for corruption because of contracts his clients received from Huntington Park.

Judges dismissed each of Martinez’s lawsuits, holding that he was suing for the sole purpose of silencing Guevara, and ordered that he pay her legal fees.

Guevara’s attorney in both cases? Thomas Scully, who is representing the plaintiff suing Ortiz and Martinez in the case involving the campaign worker.

Martinez’s attorney in both cases? Former Carson Mayor Albert “Little Al” Robles, who represented Albert “Big Al” Robles (no relation) of South Gate in his corruption trial.

“Little Al” has had ethical issues of his own, leaving the board of the Water Replenishment District of Southern California in 2018 after a judge ruled he couldn’t hold that position while also serving as mayor of Carson. And Guevara, who now goes by Linda Caraballo, was convicted in 2002 of lying about where she lived while running for office.

William Faulkner famously wrote that the past is never dead because it hasn’t even passed. In SELA, the past is just an election away.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.