- Share via

Third in a four-part series on how Latino political power has changed Los Angeles

PART III: BACK TO SOUTH L.A.’S FUTURE

South Los Angeles, the historical heart of the Black community, has been majority Latino for the past quarter-century.

Yet its elected officials — from school district headquarters to City Hall to the Board of Supervisors to Sacramento to Capitol Hill — have nearly always been Black.

Latino candidates have tried and failed to win seats, while Black leaders have openly fretted about a future where hard-fought political gains will disappear.

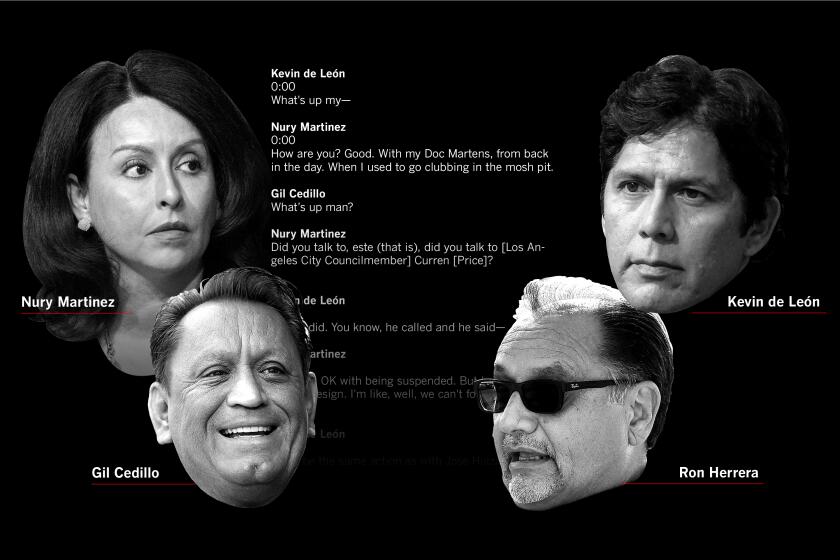

This tension was at the center of some of the most explosive exchanges in a secretly recorded conversation between four of L.A’s most powerful political insiders — all Latinos — bemoaning the lack of Latino representation across the city, and especially in South L.A., sometimes in racially disparaging terms.

“You can’t throw a rock and not hit a Mexican,” then-Councilmember Gil Cedillo said of the area, before adding, “I could support one. Maybe two [Black council members there]. But those are Latino seats.”

Few places hold as much importance in Los Angeles’ black history as Central Avenue, the birthplace of the West Coast jazz scene and a magnet for those leaving the South seeking a better life.

The four — who also included Councilmember Kevin de León, then-Council President Nury Martinez and then-Los Angeles County Labor Federation head Ron Herrera — were pilloried nationwide for their bigoted, conspiratorial views.

But the moment they yearned for may be here. For the first time in generations, a Latino has a good chance of being elected in South L.A.

In the 57th Assembly District, Sade Elhawary, Efren Martinez and Dulce Vasquez have raised the most money so far of the five candidates running to replace Reggie Jones-Sawyer, who is terming out and running for City Council. The district, which covers most of South Los Angeles, is 71% Latino and 17% Black, according to census figures compiled by Jones-Sawyer’s office.

The three candidates, all Democrats in their late 30s or early 40s, are focusing their messages on who can best bridge Black and Latino voices in this “new” South L.A. They’re employing the same strategy that propelled Councilmembers Eunisses Hernandez and Hugo Soto-Martinez to upset victories last year, one increasingly embraced by a new generation of Latino politicians in Los Angeles:

Be proud of your latinidad, but don’t dwell on it.

The road to influence has been full of trials and triumphs. From the Eastside to the Valley to South L.A. to Southeast L.A. County, columnist Gustavo Arellano dives into the key moments and alliances.

Elhawary, who is of Black, Egyptian and Guatemalan descent, says in a commercial, “I’m Black and Latina. More than anything, I’m an L.A. girl.”

The son of Mexican immigrants, Martinez said he is “of course” proud of being Latino. He insists it’s Latinos who aren’t from South L.A. who dwell on “taglines” pitting Black and Latino residents against each other.

“We have enough talent in our community — homegrown, born and raised — that we don’t need others to come and tell us what’s best for us,” Martinez (no relation to Nury or Hugo) said as we enjoyed bowls of goat birria in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood, where he grew up.

Vasquez, who was born in Mexico and migrated to the U.S. as a child, mounted an unsuccessful challenge against Councilmember Curren Price in 2022. A Latino representing South L.A. would be a “milestone,” she said. But Latinos need to be “shifting the narrative. … At some point, every district [in Los Angeles] is going to be majority Latino. And we have to be very mindful and open about how we wield that majority, and be kinder and more open than previous majorities have been.”

If their color-blind pronouncements seem to gloss over the historical nature of the moment, it’s by design. South L.A. may be majority Latino now, but history has shown that ignoring or waving off Black residents comes at political peril.

Stretching from downtown Los Angeles to the 105 Freeway, the 57th District is a snapshot of South L.A.’s past, present and future. Street taco vendors outnumber soul restaurants. Some stately churches that house Black congregations stand virtually empty even on Sundays, while Latino evangelicals pack run-down storefronts.

A Black Assembly member has represented South L.A. since 1919, when Frederick Madison Roberts became the first known Black person to serve in the California Legislature. He and his successor, Augustus Hawkins, represented the area as it became the landing spot for hundreds of thousands of Black residents who left the South during the Great Migration.

They soon outnumbered Latinos, who had lived in communities like Watts since the turn of the 20th century. A lack of citywide power for both groups tempered tensions between them, at least politically.

“Back then, if you were Jewish, Latino, Black or liberal, you didn’t have a chance on Earth” politically in Los Angeles, said Raphael Sonenshein, the dean of L.A. political history who’s now executive director of the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation.

In 1949, a multicultural coalition helped Edward R. Roybal become the first Latino on the City Council since the 19th century, representing a district that stretched from Boyle Heights to South L.A. Roybal valued his relationships with Black leaders, especially a young Black police officer named Tom Bradley who had political aspirations of his own.

In 1962, however, the alliance broke in a fight over Roybal’s council seat.

After Roybal was elected to Congress that year, Mexican American activists announced that they wanted his cousin, deputy mayor Richard Tafoya, to replace him. The move enraged Black allies — and Roybal.

He had warned that “Latins should stop thinking of the district as their very own” and that failing to consult the Black community, which had never had one of its own on the City Council, was “the biggest mistake a Mexican-American could have made,” according to a Times dispatch written by pioneering reporter Ruben Salazar.

Gilbert Lindsay — a deputy to L.A. County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, who was a white politician beloved by Black constituents — told Salazar that the move “only unified the Negro vote that much more.” The City Council went on to appoint Lindsay over Tafoya. A few months later, there were three Black council members, with Bradley and Billy G. Mills joining Lindsay.

There wouldn’t be another Latino on the City Council for 22 years.

Sonenshein called those years an “inflection point.” South L.A. went from one Black elected official — Hawkins, who joined Roybal in Congress the same year — to six. Black and Latino residents were “sometimes in alliance, sometimes in competition” in the city and in Sacramento. Each had their respective sides of town, and the unspoken detente was that it should stay that way, demographics be damned.

By the time Bradley used Roybal’s multicultural playbook to become mayor in 1973, Black politicians represented South Los Angeles, as well as Inglewood, Compton and Lynwood, and were winning city council, school board and legislative seats. Many hired Latino staffers to connect with the communities they served. Meanwhile, Latinos concentrated their efforts in the Eastside and its adjoining suburbs, which effectively isolated Latino political power until the election of Antonio Villaraigosa as mayor in 2005.

For decades, L.A. Black and Latino political leaders formed vital alliances. But these partnership now face unprecedented challenges.

USC sociologist Manuel Pastor describes South L.A. as “a tough terrain with a lot of place pride” that L.A.’s Latino political class has had trouble understanding.

The 57th District’s Black population has dropped by nearly half in the last 30 years, while the Latino population increased by 50%, according to a Times analysis of census data. Citywide, the number of Black residents is also declining. During the 1992 riots, Eastside politicos initially bragged that Latinos had largely remained peaceful. When the true scope of the damage emerged in Pico-Union and South L.A., the politicos largely kept “those” Latinos at arm’s length.

Getting someone elected in South L.A. became a priority for the city’s Latino political establishment. But those outsiders just didn’t get that the area’s dynamics were different. The disconnect was apparent on the leaked tape. Martinez and De León accused South L.A.’s Black leadership of trying to draw council boundaries that would leave out economic powerhouses, like USC, by the time a Latino was finally elected.

“You know it’s coming,” Martinez said of them. “And you don’t want that Latina or Latino to have any assets.”

“So they f— a future Latino council member,” De León said. “That’s how arrogant, just how arrogant it is.”

Jorge Nuño’s family moved to South L.A. in the late 1960s from Mexico, buying a home from a Black woman who also deeded them land in Perris because they took care of her in her old age.

“It’s always been a beautiful relationship with the Black community here,” said the 47-year-old. He runs the Big House, a three-story Craftsman in Historic South Central that serves as a community center and small-business incubator. Nuño contrasts his relationships with Black neighbors with the perspective of classmates at Garfield High in East Los Angeles, where he was bused: “I was mocked for wearing Timberlands instead of Doc Martens, and for talking ‘Black.’”

Posters from Nuño’s failed runs against Price in 2017 and Holly Mitchell for L.A. County supervisor in 2020 hang in the Big House’s main room. He said someone from the Eastside Latino political establishment encouraged him to run the first time.

“He saw a young Latino in South L.A. and put me there as a test,” Nuño said, without naming the politico. “It had nothing to do with me.”

Now, Nuño, who has endorsed Elhawary, is watching as three fresh faces compete for the 57th Assembly District seat. It’s a chance, he said, to “remove the tumor” of old-style Latino identity politics.

A bombshell recording has thrown L.A. politics into chaos. What was really being discussed? L.A. Times reporters and columnists pick it apart, line by line.

“The Eastsiders always sent their implants and tried to tell us, ‘This is your [Antonio] Villaraigosa,” he said while we sat on the porch of his home, next door to The Big House. “They used to shove someone in your face and say, ‘This is your champion.’ But in South L.A., if you ain’t about” the community’s Black-Latino essence, “you’re not going to win.”

“I love my Mexican heritage,” Nuño added, “but I love my community more — and it’s Black and brown. Outsiders will never get that.”

Pastor, who has endorsed Elhawary, pointed out that Price — who is facing corruption charges while remaining on the council — increased his margin of victory each of the three times he ran, always against Latino opponents.

“He had a staff that was overwhelmingly Latino,” Pastor said. “He worked with [Latino groups]. No way would he have won without a Latino majority. Latino representation in South L.A. is necessary, but is a Latino representative necessary? No.”

Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who has also endorsed Elhawary, remembers having a tough time convincing Latinos in South L.A. to support Villaraigosa during his mayoral runs. They didn’t see him as a fellow Latino; they saw him as someone from the Eastside.

“It’s a little bit of bunker mentality for everyone here,” the council member said. “It feels like we’re us against everyone. If I were a candidate, I’d rather knock on the door and say I went to [George Washington] Carver junior high than ‘I went to Harvard.’ Because residents then know, ‘Oh, you’re from here.’”

Harris-Dawson joked that the only people who bring up the lack of Latino political representation in South L.A. are “people who want to run for office.” Then he got serious.

“There’s a feeling we got to get in front of it happening, instead of it to us,” he said, referring to the decline of Black political power and the rise of Latinos. “We know it can happen, and should happen, given it’s a Latino city. Let’s have it happen in a way that works for everyone.”

Elhawary, Martinez and Vasquez are each claiming they best reflect South L.A., pointing to their personal stories.

Vasquez, an assistant vice president for Arizona State University’s Los Angeles operations, was dogged by criticism during her 2022 council run that she had only lived in the area since 2020, when she moved there from downtown. This time around, Vasquez is reemphasizing her original stance that South L.A. is a place where newcomers are a constant and share many of the same struggles as lifers. Her most prominent local endorsers so far are Jones-Sawyer, Villaraigosa and state Sen. Lena Gonzalez.

“If you have a smart, hardworking person who’s there with good motives, then you should be able to represent an area that you care about and that you currently live in and that you’re creating roots in,” said Vasquez, 38, as we talked at a pupusería near USC. “It’s both about where you’ve been — but also, where are you going?”

Despite a huge demographic swing, the ‘Black seats’ on the City Council long remained uncontested, leaving Latinos vastly underrepresented.

Though born and raised in Florence-Firestone, Martinez is better known politically in nearby Huntington Park, where his consulting business is based and where he has unsuccessfully run for City Council three times. When he ran for Assembly in 2020, Martinez surprised South L.A.’s political class by placing first in the primary against Jones-Sawyer. He blamed his eventual loss on then-Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon and the California Black Legislative Caucus, which poured millions of dollars behind Jones-Sawyer in the general election.

This time, Martinez has outraised Elhawary and Vasquez. The bulk of his endorsements come from Southeast L.A. County elected officials, but he also counts Supervisor Janice Hahn and Assemblymember Mike Gipson — both whom represent parts of South L.A. — as supporters.

“South L.A. has proven itself that we want one of our own from our community, whether that be me or not,” said Martinez, 43. He brought up Elhawary, who attended junior high and high school in northeast Los Angeles and Pasadena.

“They’re trying to put their finger to cover the light on what’s really going on, which is they moved [Elhawary] into South L.A., to run for the seat,” he said.

Who are “they?” I asked.

“Well, the other political folks,” Martinez said, without elaborating further.

Elhawary has spent the majority of her career as an organizer for Community Coalition, the South L.A. nonprofit that has centered Black and Latino unity since its founding in 1990. In recent years, it has begun to assert itself politically in Los Angeles: Mayor Karen Bass is one of its founders and Harris-Dawson is a former president. Bass and Harris-Dawson have endorsed Elhawary, as has nearly every other South L.A. elected official, in addition to Supervisor Hilda Solis and Councilmembers Hernandez and Soto-Martinez.

Elhawary’s mom, Audy Vasquez-Ramirez, worked in South L.A. at a Head Start program off Crenshaw Boulevard when she was pregnant with Elhawary.

“She has seen Black and Latino people work together since she was so little,” the Guatemalan immigrant said of her daughter. “But she was more accepted by Blacks. They were much more giving. Latinos would say, ‘How is she Latina?’ A lot of them still don’t believe that she is.”

At her campaign kickoff in September in a parking lot off 53rd Street and Vermont Avenue, Elhawary wore a gray T-shirt that said “South Central Strong” under a cream-colored sport coat.

“Folks are really proud that this is where they’re from, and they want to be able to say, ‘Even the folks that represent us know what we do, what we’re about,’” said Elhawary, 36.

After that despicable recording of an anti-Black conversation among Latino City Council members, this victory was the reassurance our city needed.

The rally felt like a homecoming. A DJ spun equal parts Stevie Wonder and Marc Anthony. Elhawary hugged and high-fived people, including Deion Barrientos, a UCLA student of Salvadoran and Belizean descent who remembered her from when he was at Fremont High and she helped him and his peers push for a wellness center.

People in South L.A. “need to see someone like them to run,” Barrientos said. “No one is going to do anything about us except us.”

“We need that representation here, from people who are from here,” said Alba Nuñez, a Watts native and member of the same Latina sorority, Lambda Theta Alpha, as Elhawary. Nuñez and her sorority sisters performed a line step routine, along with chants that a delighted Elhawary mouthed word-for-word.

“She represents us in the way we should be represented,” Jelani Hendrix, president of the Black Young Democrats of Los Angeles, said in a short speech. “You can organize Black people, that’s good. You can organize brown people, that’s good. When you can organize Black and brown people, people start watching.”

On the first weekend of December, Elhawary, Martinez and Vasquez were all working South L.A. for votes.

Vasquez held a fundraiser at her home. Elhawary and her volunteers went to the latest CicLAvia, which spanned Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard from Central Avenue to Leimert Park. Martinez was also at CicLAvia, then handed out free ice cream cones at a nearby 5K run.

I went to CicLAvia hoping to catch the candidates in action, but they were gone by the time I arrived. Fun, not politics, was on people’s minds. Black and Latino families skated or walked or biked. Boogie funk, oldies-but-goodies, hip-hop and sierreños effortlessly blended, as did the scents of barbecue and Cuban food.

Five Democrats are running in the Los Angeles Assembly race: Efren Martinez, Sade Elhawary, Greg Akili, Tara Perry and Dulce Vasquez.

Yenifer Lucio, 34, walked her beach cruiser across Avalon Boulevard with some friends.

“It’s important to have Latinos in office, because we’re who now lives here,” said the daughter of Salvadoran and Mexican immigrants. She hadn’t heard of Elhawary, Martinez or Vasquez and didn’t vote in the last election. “But it shouldn’t be the only reason people vote for someone. They have to actually be good.”

A block away, Eric Johnson walked down Jefferson Boulevard toward a Prince liquor market. Vacant warehouses and factories stretched as far to the west as we could see. The 56-year-old said he was one of the last Black residents in the area, but he didn’t mind his Latino neighbors.

He hadn’t heard of the 57th District candidates either, but he had a request for them.

“I hope they respect that Black politicians looked out for Hispanics all the time,” he said. “They did good for everyone. I hope that continues.”

As the primary approaches, Martinez has unveiled the bare-knuckle tactics common in his political base of Southeast L.A. County.

Earlier this month, he accused Elhawary and Vasquez in cease-and-desist letters of being behind a potentially damaging text message to voters. The message included a link to commercials describing a lawsuit alleging he and Huntington Park Councilmember Graciela Ortiz were liable for the actions of a campaign worker, who pleaded no contest to sexual misconduct with an underage volunteer. Both of his opponents have denied any involvement in the text message.

Martinez, who was friendly when we met for birria and had quickly responded to follow-up emails, hasn’t gotten back to me about this development. But I’m now surer of the impression I had of him after we first talked.

He wants to be the first Latino to represent South L.A. in generations.

And he won’t let anything get in his way.

Times data reporter Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.