- Share via

SAN BENITO COUNTY, Calif. — In case it wasn’t obvious on the two-lane highway that carves through golden hills, cow pastures and rows of grapevines, a sign inside the roadside Paicines General Store makes the point clear: “Welcome to the country.”

When Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas was a boy in the 1980s, his grandmother would walk him and his brother to the store for ice cream before heading to her night shift at a local cannery.

“I remember coming here often, and not much has changed,” Rivas said during a recent stop inside, surrounded by racks of cowboy hats, rodeo posters and a bulletin board pinned with business cards for horseshoers and beekeepers.

Rivas grew up in farmworker housing on the fields east of the store. On Fridays, he recalls his grandfather driving the boys up the road to join the picket lines outside a supermarket during the United Farm Workers grape boycott. Rivas and his family still live nearby in suburban Hollister, where shopping centers crawl with a mix of gleaming SUVs and mud-spattered pickups.

This is the place that shaped Rivas, who recently became one of the most powerful politicians in California after a nasty year-long struggle that divided Democrats in the state Capitol. He’s the first Assembly speaker in a generation to represent a rural district — and the first from San Benito County, a small Central California county with a quirky record as the state’s political bellwether.

“For too long, it’s been basically Los Angeles and San Francisco that have determined political leadership,” said Leon Panetta, President Obama’s secretary of defense and a longtime congressman from California’s Central Coast who has known Rivas for years.

“It’s really important for him to bring that perspective to Sacramento, which too often basically listens to the loudest voices, and not always the most important needs.”

Rivas toppled the prior speaker. Rep. Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood), by pulling together a coalition of Democrats who hail from districts both north and south, urban and rural, coastal and inland. His supporters included some of the Legislature’s most ardent progressives, as well as some of its most conservative Democrats.

An unusual mix of ideologies is woven throughout Rivas’ story. He’s proud of his grandfather’s roots in the farmworker rights movement. As a county supervisor, Rivas helped pass one of California’s first local bans on the oil-extraction method known as fracking. His progressive record in the Legislature has won him plaudits from both labor unions and environmentalists.

But his rise in politics came through working with more moderate business-aligned Democrats, and his wife was a registered Republican for at least 14 years until switching to a minor party last year.

Rivas’ brother — whom he calls his “closest adviser” — is an executive for the soda industry’s lobbying arm and a political strategist for a donor network largely made up of Silicon Valley venture capitalists that seeks to counter the sway that public employee unions have in California politics. Rivas’ cousin works for the group too and, until earlier this summer, shared a loft with Rivas near the Capitol where lawmakers often gather over dinner and wine.

So far Rivas has managed to navigate California’s varied political universes largely by playing nice. He emphasizes his role as a listener more than a speaker. He’s been cautious about laying out a political agenda. In a Capitol full of swagger, Rivas’ vibe is decidedly aw-shucks.

“He can bring different forces together,” said longtime labor leader Dolores Huerta, who worked with Rivas’ grandfather during the farmworker rights movement and has remained close to the family. “He has a very humble temperament.”

But as the Legislature heads into the chaotic final stretch of the 2023 session that ends on Sept. 14, Rivas will be put to the test. Lawmakers must decide the fate of numerous controversial proposals that divide business and labor — including providing unemployment benefits for workers on strike, increasing employee sick days and boosting the minimum wage for healthcare workers.

Lawmakers also must resolve battles that pit tech companies against consumer advocates and settle debates dividing Democrats, such as whether to stiffen penalties for sex traffickers, how best to confront the scourge of fentanyl and whether large companies should be compelled to do more in the fight against climate change.

The decisions the Assembly makes in the coming days will reveal whether Rivas uses a heavy hand or a light touch as he works to unify Democrats. The months that follow will show whether he has a clear agenda as a leader. Rivas used his small-town charm to build power. But will he be effective in steering a caucus dominated by big-city liberals?

“He’s going to have to balance the needs of the state, the needs of the caucus and the individual needs of members,” said Assemblymember Isaac Bryan, a Los Angeles Democrat who is one of Rivas’ closest allies. “But he’s proven that that kind of nice-guy thing that he gets a little flak for is actually one of the keys to making that all work.”

Rivas may prove to be more attentive to issues affecting rural California, such as water and wildfires, said Assembly Republican leader James Gallagher, who also represents an agricultural region. But he thinks Rivas will largely be beholden to Democrats’ left wing.

“He has a challenge,” Gallagher said. “He’s got a lot of progressives in his caucus that I think are moving things in a direction that ... have not been good for California. From my standpoint, we need to move things more towards a reasonable middle. And I think that’s an opportunity for him, to show that we can do that.”

Home to millions of voters and political machines that span generations, California’s big cities have long dominated Democratic politics in the state. San Francisco gave rise to Govs. Gavin Newsom and Jerry Brown, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris. Los Angeles is home to seven of the last eight Assembly speakers, including Mayor Karen Bass and former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

Yet tiny San Benito County developed a reputation in the early 2000s as the state’s political prognosticator, with results at every election that closely mirrored the statewide vote.

“San Benito’s uncanny predictive power” on ballot measures and top of the ticket races was so pronounced that political scientists published a study about it in 2011. “The phenomenon of San Benito is a reflection of the changing political geography of California and the cleavages that dominate its politics: north vs. south, east vs. west, and urban vs. rural,” says the report in the California Journal of Politics and Policy.

Nestled between the more conservative Central Valley and the liberal coast, San Benito, the study concludes, is influenced by both, illustrating “the broad geographic forces shaping contemporary California politics.”

Rivas and his brother Rick are part of that story. Inside their mother’s Hollister home, pictures of the pair hang in the hallway: as toddlers playing with a puppy, as teenagers smiling beneath the shade of a tree.

In those years, Rick seemed poised to become the family’s politician, said their mother, Mayra Flores: he was the rare high school student who showed up at school board meetings.

“One time Rick went because there was no soap in the bathroom. So he went, you know, to fight for that,” she said.

Robert was busy playing basketball, running track and field, and working at restaurants and farmers markets, Flores said.

After the brothers returned home from college, they got their first experience working together on a political campaign when they helped now-Sen. Anna Caballero run for Assembly. She won, and hired Rick to work in her Sacramento office and Robert to work in the district helping constituents.

It quickly became clear to Caballero that Rick’s talents lay in the tactical side of politics — running campaigns and winning elections — while Robert’s skills were in relationship-building. Their work with Caballero launched the brothers into adjacent political careers, with Robert following the path to elected office and Rick pursuing work as a campaign strategist.

“Robert is a kind of person that listens, and that is very collaborative,” Caballero said. “He has the ability to listen and figure out what people are trying to do, what their goals are, what they’re interested in.”

While on the San Benito County Board of Supervisors, Robert Rivas persuaded a Republican colleague to join him in the 2014 campaign to ban fracking.

“I had to be convinced, and I sat and listened to him,” said Anthony Botelho, a fellow county supervisor at the time. “I lost a lot of friends over it. I lost a lot of credibility with a number of landowners and Republicans. But it was the right position because of flaws in the process of fracking.”

Rick Rivas went on to work for Govern for California, the donor network led by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s economic advisor David Crane that includes many venture capitalists and other business leaders.

Crane argues that public employee unions have too much clout in state government decisions, leading to greater spending on pensions and salaries without sufficient attention to the quality of schools, healthcare and other government services. His group tries to counter public-sector unions through lobbying and campaign donations, and has given to scores of lawmakers across the ideological spectrum over more than a decade.

Rick Rivas and Crane both declined to be interviewed for this article.

As a political advisor to Govern for California, Rick Rivas helps the group evaluate candidates to support, and many of the Assembly candidates the network gave money to last year supported his brother in the speakership fight. It contributed to the rift among Assembly Democrats, with Rivas’ opponents saying his brother’s connections essentially allowed him to buy power.

Though Rivas is close with his brother, he is quick to point out his independence. Rivas supported legislation to create single-payer healthcare in California and allow legislative employees to unionize, both bills that Govern for California lobbied against.

“I am my own person. I make my own decisions,” Rivas said. “The only people that influence me are, certainly, the people I represent [and] the members that I work with in the Legislature.”

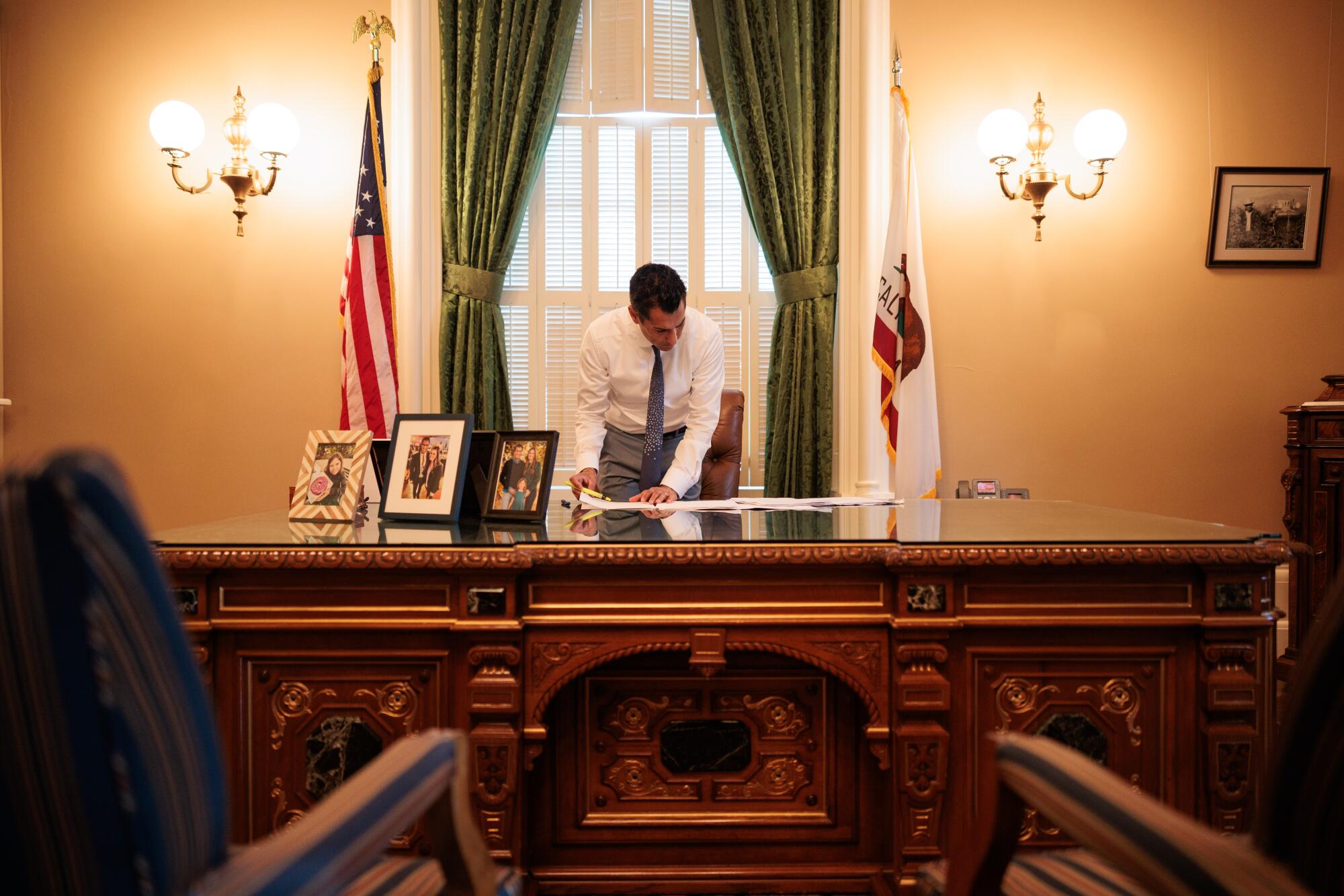

Early on the morning of June 30, the nameplate that hangs outside the Assembly speaker’s office door was blank. The previous speaker, Anthony Rendon, had moved out and Rivas had not yet been sworn in.

Inside the office, Rivas stood behind the ornate wood desk going over his inaugural speech. His mother paced nervously as his most loyal supporters filtered into the room. They included Democratic assemblymembers from Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area — the core group that helped Rivas wrest the speakership from Rendon. After the long struggle for Rivas to take power, the energy in the room was victorious.

“All right, here we are!” Assemblyman Matt Haney (D-San Francisco) said as he walked in, taking in the speaker’s spacious private office. “I haven’t been back here very much.”

Amid the lavish beaux-arts furnishings that come with the office, Rivas had decorated with a few personal items: On the wall hung a black and white photo of his grandfather, standing in a field with an arm resting on a tractor. On the mantel above the fireplace stood a framed paystub — the one his grandfather received in 1987 from Almaden Vineyards.

Across the hallway inside the Assembly chamber, Rick Rivas arranged seats for their family members to watch the swearing-in ceremony. As it began, a who’s-who of California politicians entered the chandeliered chamber. Newsom, Pelosi, Bass and Villaraigosa were among those who took seats on the dais. Huerta and Caballero sat near Rivas’ family in the front row.

Rivas delivered a speech that emphasized the values he took from his upbringing: “Love, community and service.” He called on lawmakers to work with him to ameliorate homelessness, protect the environment and improve roads and schools, saying they should focus “less on how many bills we can pass and more on the impact we are having.”

“Sometimes this will mean going back and fixing something rather than passing a new law,” Rivas said. “It may mean saying no to an interest group that’s had our back in the past. It may mean reaching out to a colleague whose beliefs are different than our own.”

Applause rose from the chamber. Now comes the hard part: making those words come true.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.