- Share via

In Sacramento, county inmates sometimes go weeks without feeling an outside breeze on their faces. In San Francisco, some haven’t seen sunlight in years. And in Los Angeles, detained people complain of cells covered in blood or feces.

Across more than 120 jails in California’s 58 counties, conditions behind bars can vary wildly, from the sprawling campus of San Diego’s women’s jail to the 60-year-old “dungeon” known as Men’s Central jail in Los Angeles.

The brutal 20-minute clip is one of a few dozen graphic videos saved to a thumb drive picked out of the trash by one inmate, and later secreted out of the jail by another.

But there’s one thing California’s local lockups have in common: prisoners who spend weeks, months or even years in isolation without any meaningful human contact or rehabilitation.

Assemblymember Chris Holden is trying to change that. The Pasadena Democrat introduced Assembly Bill 280 this year to limit “segregated confinement”— what is colloquially known as “solitary.” Generally, that means locking people in cells for 22 or more hours per day.

The legislation aims to make state prisons and county jails more humane by restricting isolated confinement to 15 consecutive days, or 45 total days in a six-month span. Even during that time, lockups would be required to let people out for at least four hours a day for recreation and rehabilitative programming, including counseling and treatment services.

But even in California, where lawmakers and voters have embraced many progressive changes to the criminal justice system, scaling back the use of solitary confinement has proven difficult. Some elected officials, including the governor, suggest it could lead to increased violence behind bars.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a similar bill, arguing that while the issue was “ripe for reform,” the proposal was “overly broad” in a way that could “risk the safety of both the staff and incarcerated population within these facilities.” Instead, he directed his state prison agency to rewrite rules to restrict segregated confinement to “limited situations,” which are currently being drafted.

Gov. Newsom vetoes bill to end indefinite solitary confinement in California, citing safety concerns

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Thursday vetoed a bill to limit solitary confinement in California’s jails, prisons and private detention centers.

But his veto message was silent on county jails, which Newsom doesn’t control and where advocates say there are some of the worst conditions due to overcrowding and understaffing. More decentralized than prisons, jails are typically run by elected sheriffs in counties that vary from large and urban to remote and rural. Depending on local politics and funding, how a sheriff runs jails in one county could be radically different from the next one over.

Despite significant support in both the state Senate and Assembly, the bill still faces an uphill battle. Corrections officials have quietly lobbied against the measure, and lawmakers have been warned that the requirements could force the state to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to pay for renovations, increase staff and defend against lawsuits.

But if passed and signed into law, Holden’s bill would bring California’s corrections facilities in alignment with United Nations guidelines on the use of isolation, something prison researchers and reform advocates say is particularly needed in local lockups where most incarcerated people are waiting for trial and have not been convicted of a crime.

“Frankly, it’s an unrecognized scandal that so many people are suffering so significantly in these environments,” said Craig Haney, a UC Santa Cruz psychology professor who has studied the long-term effects of solitary confinement.

Sheriffs who run the jails see a physically impossible, dangerous and costly task ahead if AB 280 passes. They use confinement to separate inmates who they say are violent, gang-affiliated or accused of high-profile crimes.

In some jails, even general population inmates spend so much time locked in their cells that they would fall under the bill’s broad definition of segregated confinement. Many jails simply aren’t designed with enough space to safely give everyone more time outside their cell, sheriffs argue, or enough staff to watch them.

“It’s not as simple as this legislation makes it out to be,” said California State Sheriffs’ Assn. President and Tulare County Sheriff Mike Boudreaux. “More and more oversight is being implemented into something that seems to be carrying a political narrative versus real solutions.”

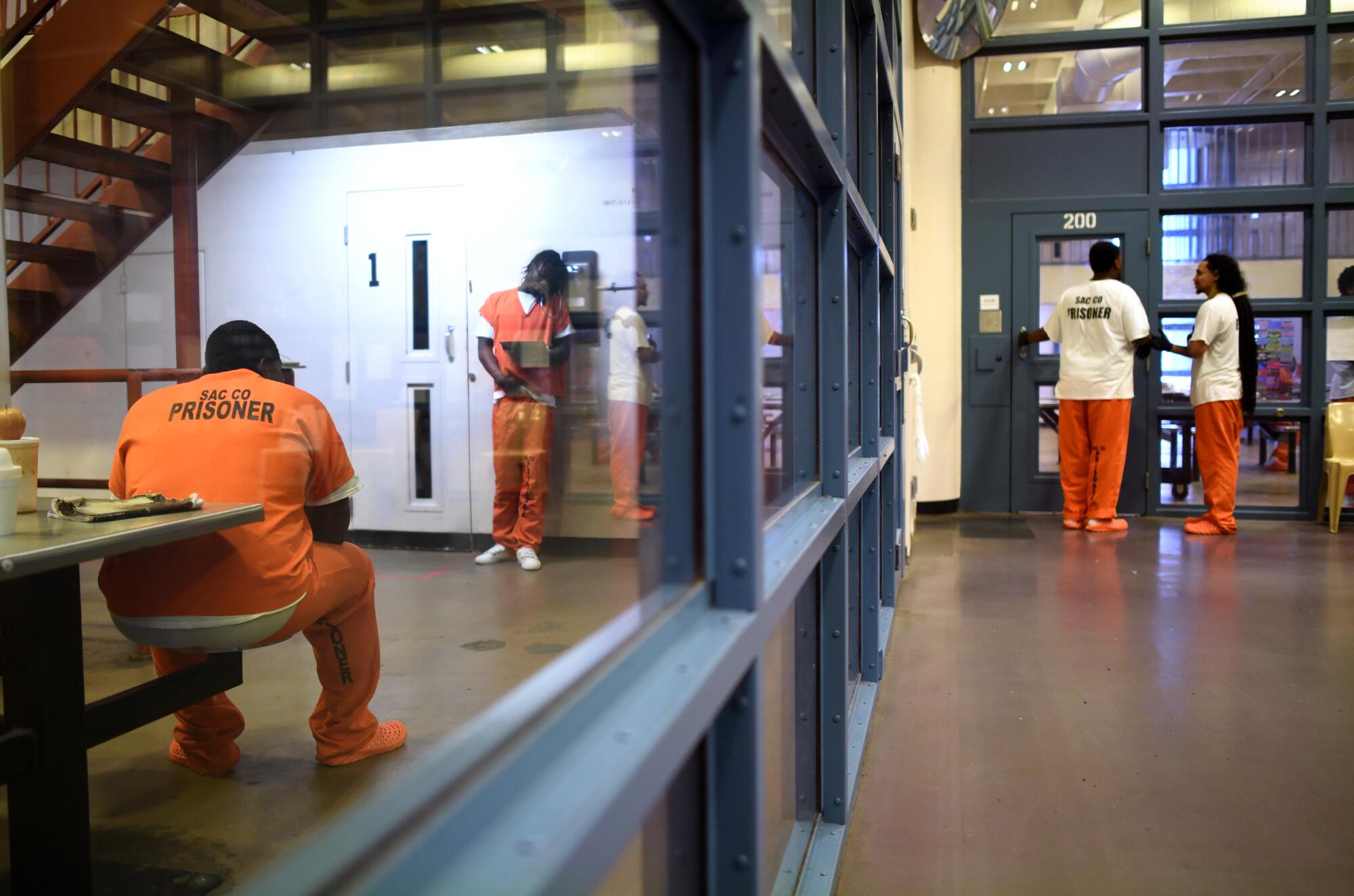

Blocks away from the state Capitol where lawmakers are debating solitary confinement sits Sacramento County’s Main Jail, a dilapidated building in the center of downtown with dingy cells and sanitation issues that in recent years has seen an uptick in in-custody deaths.

During a recent tour of the jail, a Times reporter heard people yelling and talking to themselves while in isolation, their voices amplified in the steel and concrete of their housing pod. One unit reeked of stale air and sweat.

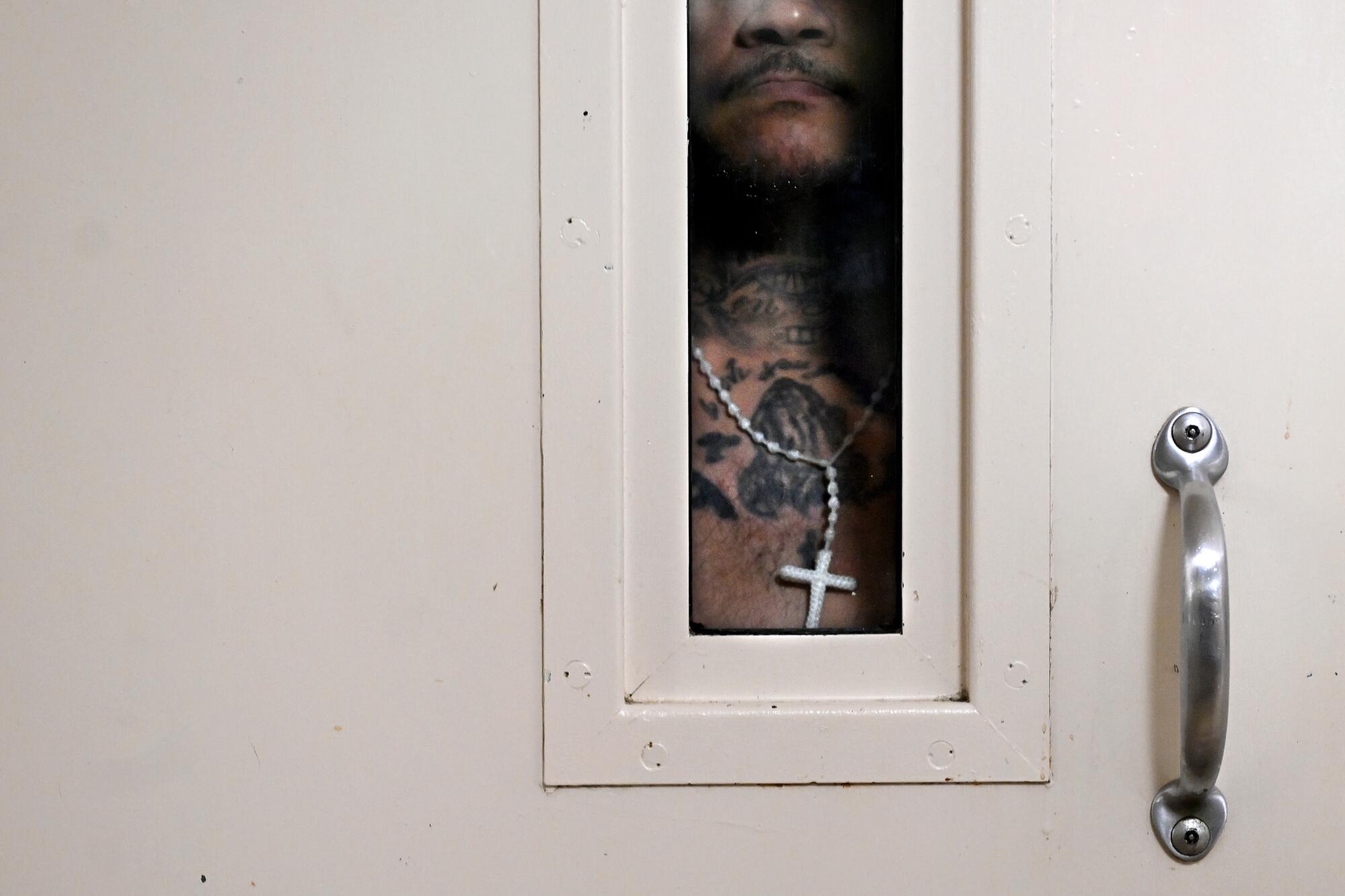

Peeking out from his cell’s glass window was Dandrae Martin, charged with murder in last year’s mass shooting that left six people dead outside a Sacramento nightclub.

So many people in the Sacramento jail have mental illness — about 60% — that the facility has become a “de facto psychiatric hospital,” said Sheriff Jim Cooper.

“There’s no place for them to go. It’s just backwards,” Cooper said. “County jails should not be psychiatric facilities.”

Under a 2020 federal consent decree, people incarcerated in Sacramento County’s main jail are supposed to be allowed to spend at least 17 hours out of their cells each week, with limited exceptions. But that still doesn’t happen.

“Dozens of people spend almost every hour of the day locked in small, dark cells. People go weeks or even months without any access to fresh air,” a 2022 report co-written by the advocacy organization Prison Law Office found. “Even when they are permitted to go to outdoor recreation, they are confined to another grim concrete space, with no grass, no exercise equipment, and dark tarps that block any view of the outside world.”

Cooper, a Democrat who was elected sheriff last year after serving eight years as an assemblyman, said he is trying to improve conditions.

He wants to reconfigure the jail’s three yards to double the recreation space for more than 1,700 inmates. Over the last year, Cooper has lobbied county supervisors to build a new jail facility that could address outstanding requirements in the consent decree and fulfill many of the legislation’s goals. They approved a more modest plan to update parts of the jail and build a mental health annex, which will take years to complete.

Cooper worries that the proposed law would add impractical new requirements. He said jails weren’t built for long-term housing and said that deputies are doing what they can to maintain safety with an unpredictable and sometimes violent population.

During his years in the Legislature, Cooper routinely disagreed with fellow Democrats over criminal justice reform policies, including the segregated confinement bill, which he did not support last year. He said his former colleagues are “misguided” in how they’re trying to solve the problem.

“Mr. Holden wants a cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all approach,” he said. “It doesn’t work.”

The jail conditions have been a decades-long problem in Los Angeles County where, according to department officials, as of mid-August 830 people were in administrative segregation — some isolated for disciplinary reasons, and others for their own protection or for broader safety and security concerns.

There is also a much larger population of people living in de facto isolation, including hundreds of severely mentally ill people who spend most of their time locked alone in their cells. Under a settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice that’s been in place since 2015, the county agreed to give severely mentally ill people 20 hours of out-of-cell time per week — 10 hours of free time and 10 hours of programming. But the county has never fully complied with that requirement.

In some areas of the jail, the conditions, both for those in isolated confinement and for those in general population, are remarkably poor. Despite regular visits from court-appointed monitors, current and former inmates regularly report being housed in filthy cells and say they’re made to sleep on floors using only trash bags for warmth.

For John, who still has pending charges and asked that his full name be withheld, the few months he spent in isolation at Twin Towers Correctional Facility in Los Angeles have stuck with him. His cell was covered in dried feces, which he ultimately decided to leave in place instead of risking disease exposure by touching it.

For the 58 days he was incarcerated on a series of charges including simple battery and several other misdemeanors, he said he typically spent 24 hours each day in a cell. A handful of times the guards offered him a chance to get out for “recreation” — but “recreation” simply entailed being chained to a table in an indoor common area, so it “wasn’t worth” being out, he said.

“I felt a little bit less than a human being the whole time I was in there,” he said. “It was subhuman conditions — and then there’s the toll it takes on your mind.”

Unlike some people living in extreme isolation, John was not in solitary because of bad behavior or the nature of his crime: He was isolated because he admitted to staff that he was suicidal, he told The Times. Now the 40-year-old is free and in sober living, where he said he’s been off drugs for several months.

“If you’re spending time alone at home you have a television or something to harness loneliness or depression or deep sadness,” John said. “But when you’re in solitary you don’t have that. You don’t have the luxury of grasping onto something for sanity. Maybe you work out. And you sleep. That’s all there is.”

The Sheriff’s Department said it couldn’t identify the situation John described without more specific information, but that it takes all allegations seriously.

The Los Angeles County jails — seven facilities that together comprise the largest jail system in the country — house nearly 13,000 people. Roughly half the population is being held pretrial, and 42% have mental health needs.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna opposes the changes being debated in the state Legislature, arguing that the proposed restrictions on segregated confinement would hamper the jail’s ability to manage inmates with “severe and volatile” mental health problems.

“Segregated confinement must always be a readily accessible option not only for these inmates but also for others who have a higher risk of encountering retaliatory violence based on their alleged crimes, gang affiliation, or other factors,” he wrote in a letter to lawmakers.

One county over in Riverside, Sheriff Chad Bianco had similar concerns. Despite his jail’s relatively reserved use of isolation, Bianco questioned whether further reductions would be safe and said the number of cells in each pod would make it “physically impossible” to let people out of their cells for the requisite four hours per day.

Riverside County’s five jails hold a total of about 4,000 inmates, with fewer than 100 in segregated confinement, officials said. Those in segregation are frequently housed in two-man cells, and some are allowed out together in small groups. When a reporter visited a segregated housing unit in August, several men were calmly mingling outside of their cells.

Some inmates — such as the elderly or those with controversial charges — would be at a greater risk of violence if they couldn’t be segregated, Bianco said. Others, such as those with a history of attacking or killing their cellmates, couldn’t be sufficiently separated from more vulnerable people.

“There is absolutely no one with common sense or any knowledge of how a jail or prison operates who would think this is a good idea,” he said and invited lawmakers to tour the facilities.

And in San Francisco, where the county jails are also facing legal troubles over lockup conditions, there’s hardly a day that Capt. James Quanico isn’t several deputies short of what it takes to efficiently run the jail.

The county’s San Bruno facility holds about 630 people, and when a reporter visited earlier this month, one man exercising in the indoor yard said he had not been outside in two years.

In recent months, Quanico said, he’s moved dozens of people out of administrative separation, bringing the number still there down to roughly 90. He also created a new housing pod of around 20 previous administrative separation inmates who can now be in a group, which helps them get out of their cells more often.

The proposed legislation being considered by California lawmakers, which is similar to recent changes in New York, would eliminate the use of isolation for vulnerable populations, including those with serious mental and physical disabilities; pregnant and postpartum people; and anyone younger than 26 or older than 59. It would also require regular mental health checks, stringent documentation of when segregation is used and increased out-of-cell time for recreation, meals, programming and treatment.

Years of research show that prolonged isolation can exacerbate mental illness and lead to hallucinations, psychosis and suicidal thoughts.

“Isolation itself is what does the damage,” Haney said. “It almost feels like [jails are] designed to make mental health problems worse rather than better.”

Supporters of the proposed law contend that sheriffs and jail officials who oppose it are doing too little to find reasonable and safe alternatives to isolation.

“You can’t just put people into a box and not have a plan,” said Hamid Yazdan Panah, advocacy director for Immigrant Defense Advocates.

Activists are pushing back against Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to transform California’s oldest prison into a Scandinavian-style rehabilitation center.

Newsom hasn’t indicated whether he would sign this year’s legislation, but recently said he is still working with the Legislature and the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to “land on an agreement” for segregated confinement in prisons.

Time is running out for negotiations. The bill is scheduled for a critical committee vote on Sept. 1, which could decide its fate. The last day for lawmakers to pass bills this year is Sept. 14.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.