Newsom’s plan to transform San Quentin prison lacks details but is moving ahead

- Share via

MARIN COUNTY — Tucked in the back corner of San Quentin State Prison’s sprawling campus here sits a dilapidated warehouse, a humdrum building that’s fallen into disrepair since the days it was used as an office furniture factory.

It’s also ground zero for Gov. Gavin Newsom’s ambitious $380-million plan to transform the state’s oldest prison into a sweeping rehabilitation center modeled on the Scandinavian approach to incarceration, which focuses less on severe punishment and more on preparing individuals for life after prison.

Gov. Gavin Newsom this week will announce plans to remake San Quentin, one of the state’s most storied prisons, using a Scandinavian prison model that emphasizes rehabilitation.

Newsom’s vision for San Quentin builds on the prison’s already expansive programming by layering on more robust job training courses, additional substance-use and mental-health treatment and expanded academic classes. The plan fits into Newsom’s broader goal of reducing the incarcerated population, largely through treatment and prevention programs and a handful of prison closures, and builds on his prior decisions to impose a moratorium on the death penalty and shut down the execution chamber at San Quentin.

Newsom proposed the renamed “San Quentin Rehabilitation Center” in March, alongside leaders in the criminal justice reform movement, which advocates for funneling money toward rehabilitation, diversion and prevention programs and rolling back the state’s tough-on-crime laws of the 1980s and ‘90s. In May, Newsom announced an advisory council set up to implement his vision by 2025.

But despite the initial fanfare over the project, lawmakers, prison closure activists and the Legislature’s own nonpartisan financial advisors grew increasingly alarmed in the weeks following the announcement over the plan’s murky details, rushed timeline and high cost.

After initially rejecting his funding request for the overhaul, lawmakers relented in June and approved the money Newsom’s administration says is needed to tear down the old furniture warehouse and make room for what California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation officials envision as a college campus-like setting of new programs.

The Condemned Inmate Transfer Pilot Program has moved more than 100 people off of death row at San Quentin State Prison and the California Central Women’s Facility and into other housing locations, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

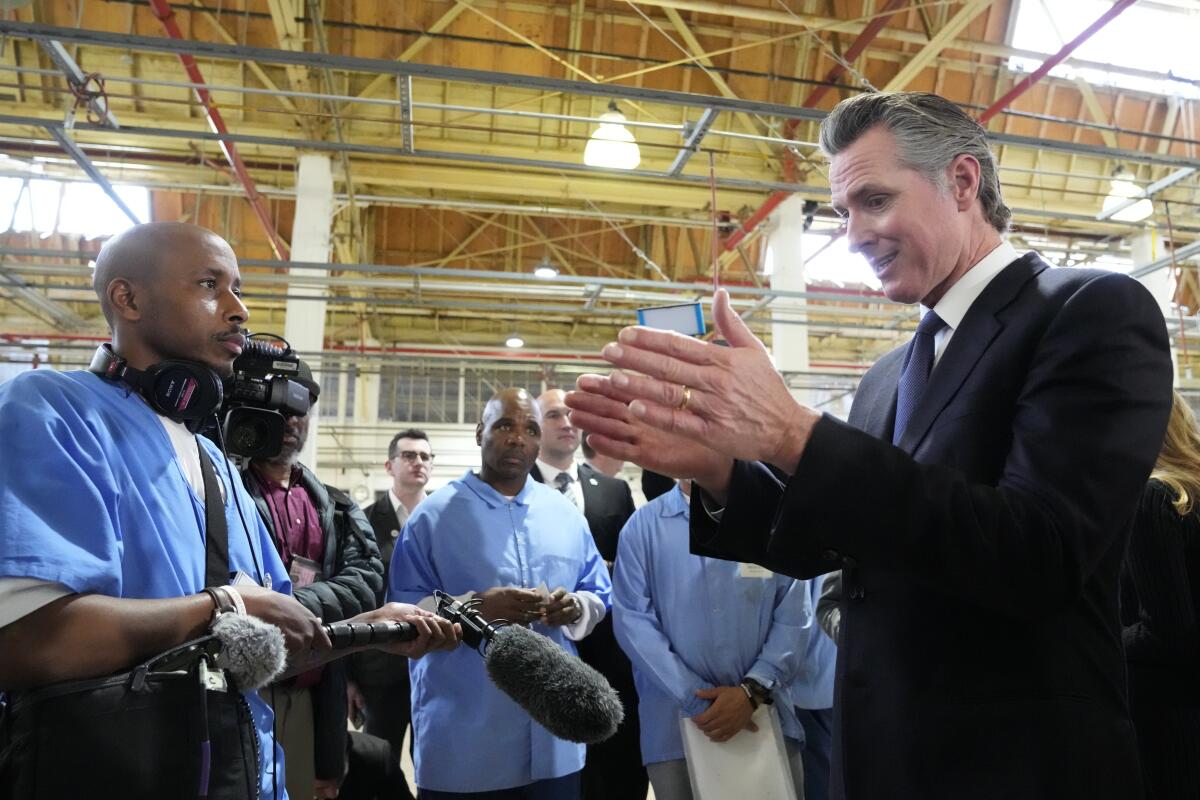

“There are many ways to light a spark and launch an initiative,” Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, whom Newsom tapped as lead advisor to the transformation council, said during a Wednesday media tour of San Quentin.

“You put out a vision and then you get to work and you make it happen.”

Steinberg acknowledged anxiety around the transformation. But he said hard work is underway to provide the Legislature and the public much-needed details on changes planned for the prison in a December report. In the meantime, he said, concerns being raised should not slow progress.

Much of the apprehension surrounding San Quentin’s transformation focuses on a damning May report from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, which offers independent advice to lawmakers. Although Newsom’s goals for San Quentin deserve some consideration, the analyst’s office wrote, the plan lacks details and objectives to determine its merit. The report warned lawmakers that total costs to reconstruct parts of the prison and operate its new programs were uncertain, and criticized the expedited 2025 timeline as “unnecessary and problematic.”

The analyst’s office encouraged lawmakers to reject Newsom’s funding request and instead mandate a study on how best to accomplish Newsom’s ambitions for developing a prison heavily focused on rehabilitation.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and California lawmakers agreed to a $310.8 billion budget deal that will reduce investments in climate change and delay funding for kindergarten facilities to offset a nearly $32 billion shortfall.

Legislators considered those recommendations during several budget hearings this spring before finalizing the state’s $310-billion spending plan.

State Sen. María Elena Durazo, a Los Angeles Democrat who chairs a budget subcommittee that oversees prison spending, said she supported Newsom’s overall objective for San Quentin.

“On the other hand, I don’t see the details,” Durazo said. “And I’m not saying it has to be down to the letter, right? But it certainly has to be far more than what was provided to us.”

Assemblymember Tom Lackey (R-Palmdale) was similarly frustrated by the lack of information provided during budget negotiations.

“I’m not necessarily against it. But where’s the public benefit?” said Lackey, who sits on the panel that allocates prison dollars. “When we talk about rehabilitation, we also need to consider victims and victims’ families, and how are they going to benefit? I just think there’s more balance in the discussion that needs to take place. When there are big ideas like this, there needs to be big explanation.”

Criminal justice reform advocates have also flocked to the Capitol in recent weeks to blast the plan as misguided and expensive. They urged lawmakers to steer the money toward prevention programs, or spread it out to other prisons, including those that house women and don’t have the opportunities San Quentin offers its men, such as journalism courses, computer coding and college classes.

“I am formerly incarcerated, and I would love as a taxpayer to see the money going towards more programs and things that’s a little bit more realistic and more viable for people across the state. Not just at this one prison, where only certain people go there and it turns into this who deserves and who doesn’t deserve rehabilitation,” said Katie Dixon, a policy and campaign organizer for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners.

California’s decision to close the prison in Susanville rocked the town, where the consequences could be dire for residents and businesses that depend on the economics of incarceration.

Steinberg said San Quentin is a smart place to start the overhaul, because it’s “already halfway there on the culture change,” which gives the state a “chance to build the model faster than at other places.”

A major part of the general plan for San Quentin includes retraining corrections officers in an approach centered more on rehabilitation and restorative justice, a strategy that focuses on the impact of a crime and how to remedy its effects. Both Steinberg and San Quentin Warden Ron Broomfield said that officers at San Quentin are interested in those training opportunities, which they think will improve work morale among the guards.

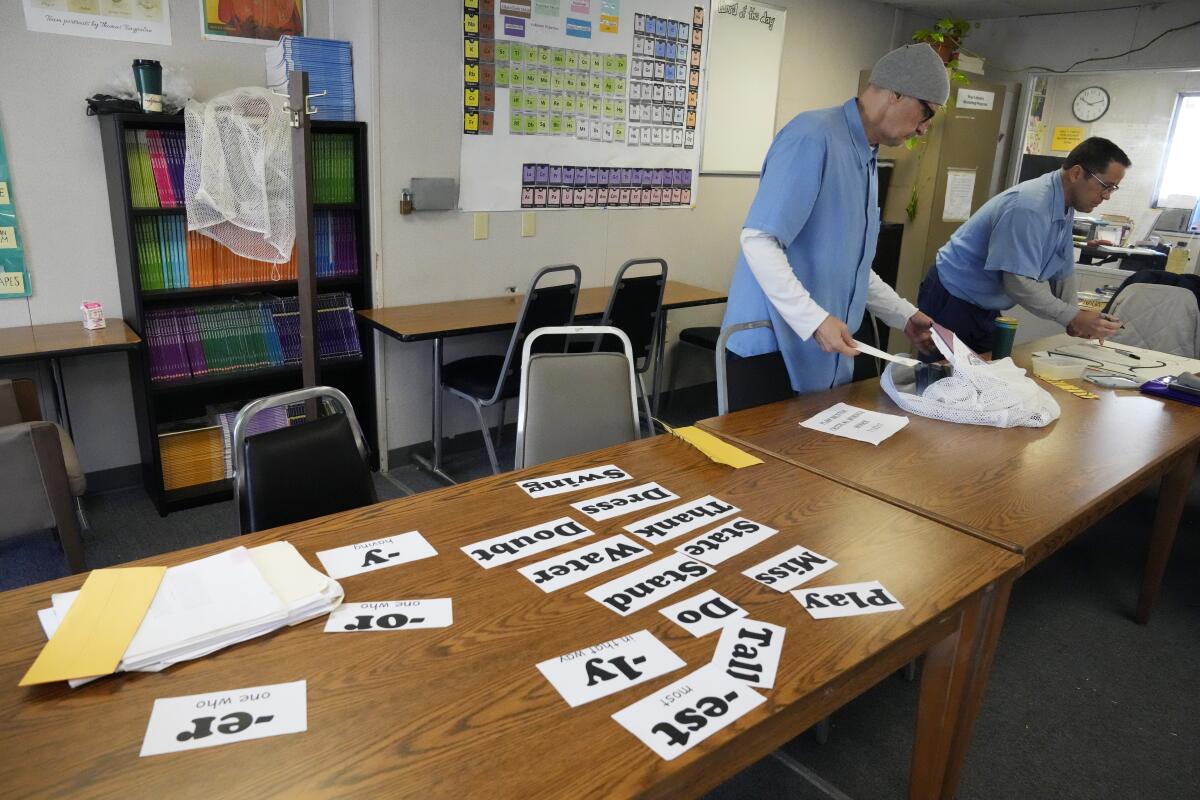

Broomfield said he envisions building up the prison’s award-winning newsroom and adding more seats to its substance use treatment programs, college classes and the technology and coding courses that lead to quality jobs upon release. The goal, Broomfield said, is to cut waiting lists so more prisoners have access to life-changing and skills-building programs that help people prepare for life back home.

For now, San Quentin’s residents are cautiously on board with Newsom’s vision.

During the media tour this week, the prison was bustling with activity, the yard full of men running the track, playing tennis and working out in the sun.

There’s been a recent shift in attitude at the prison, one more toward optimism, said Gregory Eskridge, a host for the “Uncuffed” podcast, which is made in the prison’s recording studio.

“It’s about getting people those tools and opportunities to go back out there in society and be successful,” said Eskridge, who has served more than 25 years behind bars for a murder conviction, among other charges. “I think everyone is hoping for something positive to happen.”

But there’s some skepticism too.

The new rehabilitation center is largely intended for those with shorter sentences, because they’re more likely to be released sooner. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has already begun moving the hundreds of condemned individuals off death row and into other prisons.

But San Quentin is home to people convicted of some of California’s most violent and serious crimes. Many of the nearly 4,000 people at San Quentin are serving decades-long sentences, with the real possibility that they could die in prison. Many fear being displaced from the new San Quentin, or moved out of programs they now help run.

Although they probably won’t benefit from the new rehabilitation programs in the same way that those who have shorter sentences or who are younger might, prison officials said, they could still play a crucial role as mentors to prisoners who enroll in the new programs.

Tommy Wickerd, who is serving nearly six decades in prison for voluntary manslaughter and has prior convictions for other violent crimes, said the old-timers need to be part of the plan:

“Without the lifers,” he said, “it’s not going to happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.