Before Dodger Stadium, L.A. played ball downtown, out of town and even on Catalina Island

- Share via

It’s not whether you win or lose, but where you play the game.

That’s not the wrong adverb.

This week, the Los Angeles Dodgers open their 65th season here, their 61st in the most glorious-looking ballpark in Major League Baseball.

Its contentious backstory aside, the setting floats atop Chavez Ravine with nighttime lights glowing like a crown of candlepower above the city.

This glamorpuss of stadiums is the evolutionary alpha of 150 years of sandy, stony, muddy, dusty pick-up baseball spaces across Southern California.

The first documented baseball game in town was a high school girls’ match, in 1874. (About 40 years later, an outstanding athlete named Ida Schnall would captain L.A.’s Feminine Baseball Team and appear in silent films, advertised as the “World’s Perfect Girl.”)

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Baseball was played here before then, brought by men aboard Yankee trading ships, by 49ers, even by Union soldiers before the Civil War, although it’s hard to imagine any friendly North-South game in a town where Confederate loyalties ran so high that word went out around town that anyone trying to hoist the Union flag on the town’s flagpoles would be shot.

The places they played then were pretty much wherever enough open space presented itself, but once the prospect of crowds beckoned, so did admission prices and concession vendors, and L.A. began its own distinctive hometown game of location, location, location.

In July 1886, games were apparently being played at the “Sixth Street grounds,” around Sixth and Flower, near the present-day Central Library, and the news coverage wasn’t exactly rapturous. On Christmas Eve, The Times headlined “A very ordinary game at the Sixth Street Grounds,” yet three days later, things had amped up to “Rather an exciting game at the Sixth Street grounds.”

In 1887, a “well-known sporting man” named D.J. Tobin set up a playing field in Santa Monica, near the Hotel Arcadia, and named the team the Tobins.

Yet by June 1891, baseball must have been a flagging pastime, because The Times wrote about a “scheme on foot in this city to revive baseball” with a plan for a ballfield on First Street east of the Los Angeles River, where an older playing field had once stood.

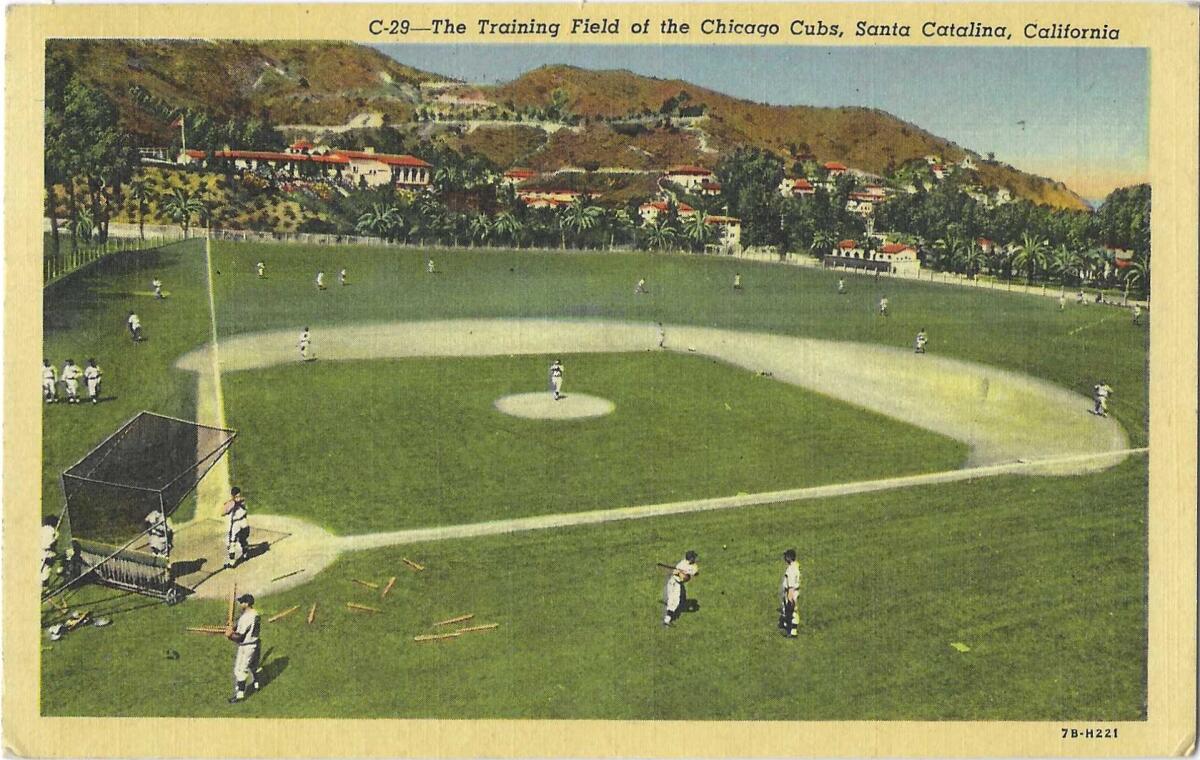

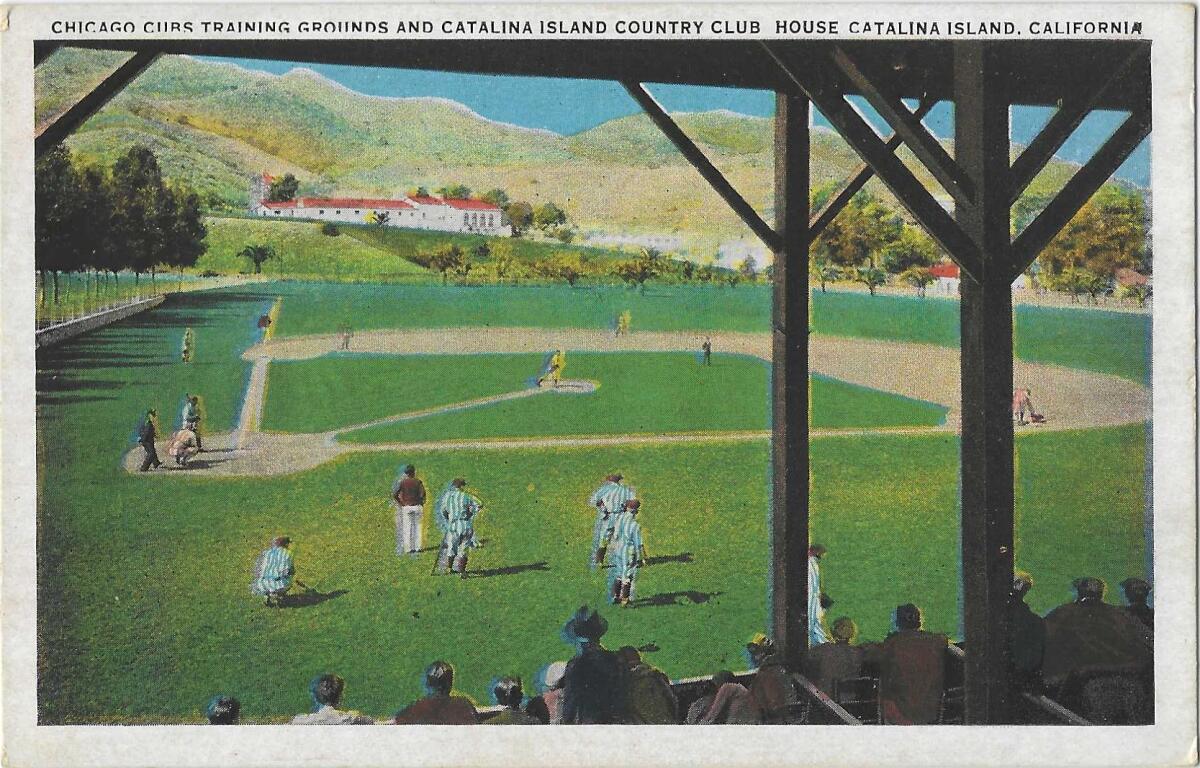

Characteristically, The Times boosted this simple idea into a crusade: “For some years past the leading clubs of the East have been in the habit of going to Florida in the winter to practice, but there is so much sickness in that country that they have made up their minds to come to this coast …” This is one bit of ballyhoo that came to pass; the Pittsburgh Pirates held spring training in Paso Robles, and then San Bernardino; the Chicago White Sox in Pasadena; and the Chicago Cubs on Catalina Island.

The First Street grounds did host games; in October 1891, “the ladies were out in force,” The Times wrote. “They filled the reserved-seat chairs, and applauded every play, good, bad, or indifferent.”

Fiesta Park, a goodly chunk of land near where the Crypto.com Arena now stands, served as the grounds of the Fiesta de Los Angeles, the city’s half-prideful, half-petulant effort to match Pasadena’s Rose Parade, and as a sometime baseball park as early as 1894.

Before the early 20th century, Agricultural Park, now called Exposition Park, near USC, was a usually unsavory place frequented by pickpockets and prostitutes working the crowd of louche sporting fans of animal races and animal fights — not a natural venue for America’s favorite, clean-cut sport. Yet in the 1880s, Saturday afternoons found local leagues playing ball, and in 1897 a charity baseball game raised money for the unemployed. Strikingly, back in May 1879, as the Los Angeles Herald reported, the all-Black Star team played there, one of a number of top-notch local Black teams, like the Trilbys, that played white teams and sometimes beat them, evidently without violent consequences.

Black teams played around town, but the home park for the White Sox team in the 1920s was in Boyle Heights. So formidable was that team that in October 1922, The Times dealt out its idea of praise for the players. “Some, if they were only white, would be stars of the first magnitude in the major leagues.” Latino teams like the Zapateros played there too, a team named for its shoemaker sponsor. In the 1930s, a new White Sox ballpark was built for the team at Compton Avenue and 38th Street.

It was at Athletic Park at the edge of downtown Los Angeles — near the intersection of present-day 7th and Alameda streets — where the California League’s Los Angeles Angels played in 1892 and 1893. In the league’s season opener, in March 1893, Stockton played the Angels, which gloried in the nicknames of Cherubs and Seraphs (which I saw spelled here and there as “Serifs,” as in a type font, a name fit for a newspaper team).

On March 25, 1893, 3,500 fans — some in the bleachers, some in grandstands, and 200 seated loftily in their own carriages — rang cowbells and blew horns to herald the entrance of the Angels. The players, in new gray uniforms, rode in triumphantly on a yellow wagon, on each side of which was a sign: “We Are Winners.” And win they did.

At Chutes Park, baseball had competition, and it wasn’t just the other team. Chutes Park was an immense amusement park, with water slides, comedy performances, miniature naval battles and Vitascope “flickers.” But when the California League puffed up into the Pacific Coast League, the Angels went along — now also nicknamed the Los Angeles Looloos — and played for several years at Chutes.

Long before Disneyland and Magic Mountain, Southern California was home to some pretty wild amusement parks, including those with lions, gators and, as one unlucky person discovered in the 1970s, an actual dead guy.

Ballparks clustered around this present-day sports corridor from Crypto toward the Coliseum, with Chutes, and Washington Park near Chutes, then expanding on the same site after Chutes closed, and Prager Park, practically within bunting distance of Chutes.

The Los Angeles Nationals played briefly at Prager, and in 1903 The Times took great delight in mocking the millionaire socialist Gaylord Wilshire — his name is still on Wilshire Boulevard and was once on a ballot as a City Council candidate. Wilshire made some of his money as an early billboard tycoon, and The Times mocked “Pillshire” when it looked like the Prager Park fences would be taken down, along with their unprofitable advertisements for “cheap cigars, breakfast food, and trouser factories …”

On the map of 1888 Los Angeles, one park was so far out of town — Hollywood-adjacent, bounded roughly by Sunset Boulevard and Edgemont Street — that it could be considered completely in foul territory. Prospect Park, as The Times wrote lyrically in September l888, was “a little beyond the northwest corner of the city, where the Los Feliz hills look down on the great plain sloping to the ocean” It possessed a field “level as a billiard table,” with a “neat fence 8 feet high,” and a ladies’ lunchroom. That was the extent of women’s welcome. “The engagement of those dizzy female ball nines was refused ... in the interest of respectability, and they will not play there.”

For a few years, beginning in about 1909, the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League played in — surprise! — Vernon, as did the minor-league L.A. Maiers and L.A. McCormicks. Then in 1913, the Vernon Tigers became the Venice Tigers in a new Westside ballpark on the grounds of the old Los Angeles Gun Club, 7 acres with the sweetest words in the L.A. lexicon: ample parking. Eight thousand fans could fit in the bleachers and grandstands, with, as a novelty, room for people in 150 cars to watch the game from their flivvers.

Trolley dodgers without trolleys. Lakers without lakes. Why some team names outlive their rationale.

But about two years later, the Tigers were back in Vernon, in what The Times called an “architectural dream home.” The team was allowed to return “with the understanding that there shall be no liquor sold in the new grounds.”

Historians have noted that the original Vernon ballpark was felicitously adjacent to Jack Doyle’s. Doyle was a retired railroad engineer who opened a boxing camp and training arena in Vernon, and a massive bar. Saloon bans in L.A. around 1907 pushed the business of thirst-quenching to the hinterlands like Vernon, and baseball fans had only to saunter over to Doyle’s for a brew; the left field corner butted right up against Doyle’s place, and between innings, rumor held that a left fielder named Jess Stovall could squeeze in a quick beer.

The Pacific Coast League team called the Hollywood Stars got launched about the same time as talking pictures, but not until 1939 did it have a Hollywood-adjacent home field. Gilmore Field was built by the 19th-century dairy-farm family that founded Gilmore Oil, Gilmore Stadium and the Farmers Market.

Silent actor Fatty Arbuckle, acquitted of rape but ever after disgraced, had briefly owned the Vernon Tigers. It was a precedent of sorts. At Gilmore, the celebrated team owners numbered the directors Cecil B. DeMille and Raoul Walsh, and actors Barbara Stanwyck, William Powell and Gary Cooper, who played Lou Gehrig in “The Pride of the Yankees.” Walt Disney and Groucho Marx had reserved boxes at the field. (No cinema costume designer seemed to have had an ownership stake; had it been otherwise, the Stars might not have committed the unforced error of spending a few seasons wearing comfy but silly-looking pinstriped shorts.)

Gilmore Oil advertised on the outfield fence, as did 7-Up, which paid $100 to a batter who hit the bulls-eye on its sign. The field was torn down in 1958, after the team was sold. At least it got a plaque … about 40 years later.

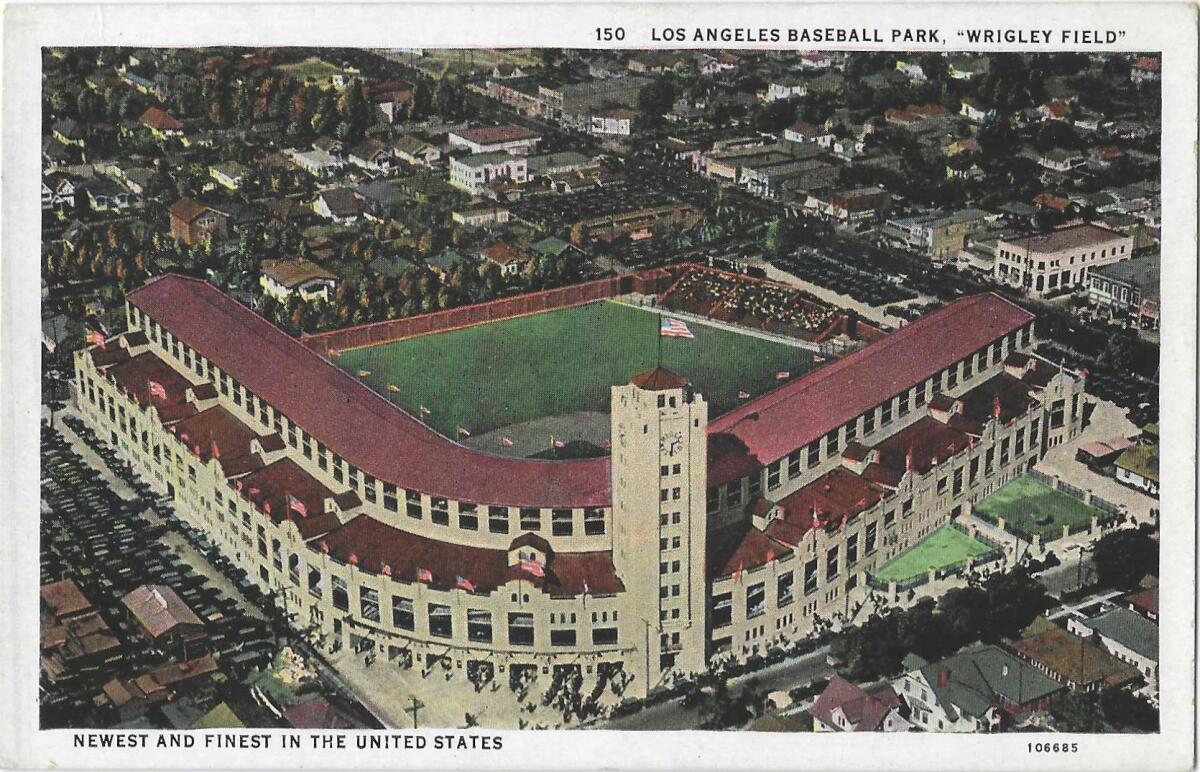

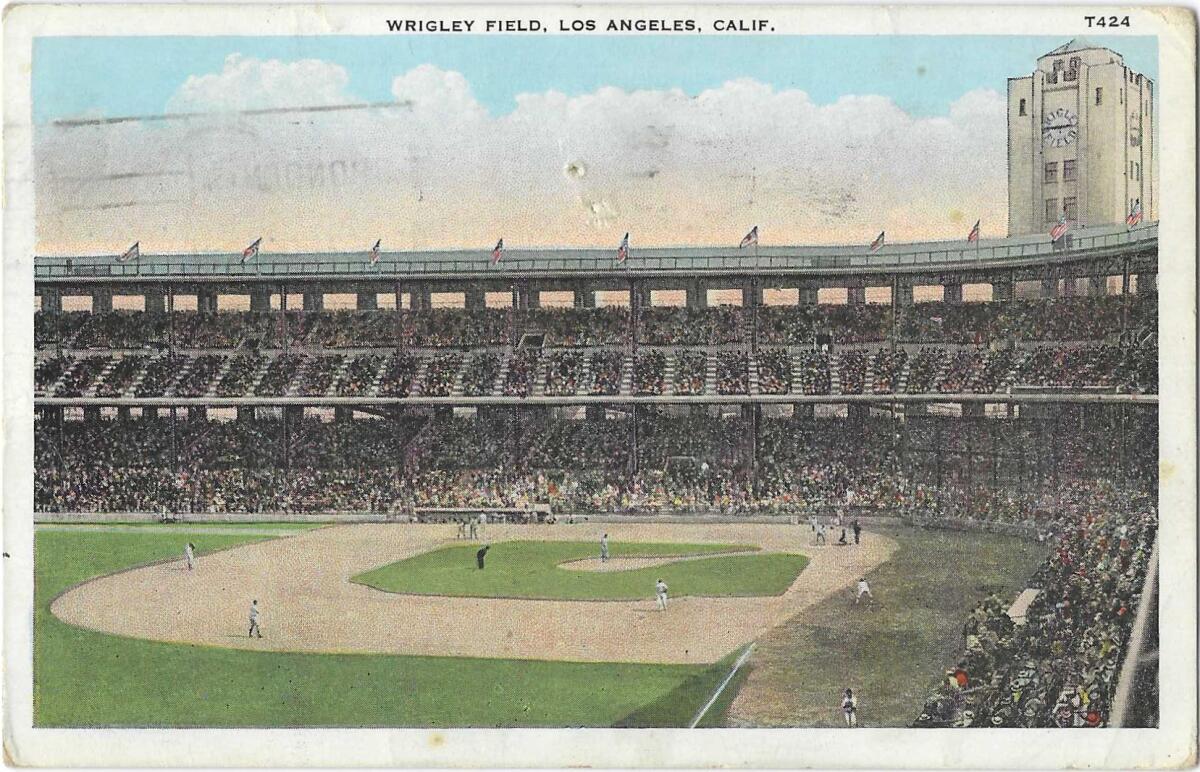

When moviemakers wanted to shoot a ballpark, they didn’t seek out Gilmore Field as often as they did Wrigley Field, the stupendous stadium built in 1925 at Avalon Boulevard and 42nd Place, just a ways east of the L.A. Coliseum.

Its cost, a cool million-five, earned it the nickname “Wrigley’s Million-Dollar Palace.” Avalon Boulevard was originally “South Park Avenue”; the name was changed in a likely bit of civic suck-uppery to William Wrigley Jr., who owned Catalina Island and the town of Avalon, where his Chicago Cubs did their spring training.

Until the Dodgers came to town, Wrigley was the biggest wheel in Southern California baseball, the man whose fortune was built on chewing gum, the stuff that baseball cards came packed with.

Wrigley owned the Chicago Cubs and the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. His name is still on his white Pasadena mansion, now the headquarters of the Tournament of Roses.

L.A.’s was the lookalike little brother of Wrigley Field in Chicago, where Wrigley’s Cubs played. The clocks on its tower faced the compass points and, instead of numbers, spelled out “WRIGLEY FIELD.” Here, the Hollywood Stars played for a few years before the Gilmore facility was built. Here, Wrigley’s minor-league Angels played until 1957, and here for one season the major league Angels took the field.

According to L.A.’s historical Homestead Blog, Times sports columnist Bill Henry cited one opening-day review of the new stadium, from which “far in the distance are the skyscrapers of Los Angeles, beneath whose towering roofs are thousands and thousands of stenographers busily chewing more gum to build better ball parks.”

Decades before its Chicago sibling, this Wrigley Field had night-game lights in 1930. Here, at a 1927 charity exposition game, Lou Gehrig’s team beat Babe Ruth’s. And here, too, in May 1963, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was the keynote speaker at a civil rights rally. Several months before the Birmingham, Ala., church bombing that killed four little girls, King connected the dots on civil rights: “You can help us in Birmingham by getting rid of any segregation and discrimination that exists in Los Angeles.”

When the Brooklyn Dodgers came real-estate shopping here in the 1950s, they bought Wrigley Field as part of an original plan for the Dodgers to play there. But it didn’t work out, and the Dodgers’ owner and the city swapped Wrigley Field for the spectacular property in Chavez Ravine. Wrigley Field — oh, the humanity — was leveled in 1969 and the city put up a community center and park.

There is one more ballpark worth the mention — the Los Angeles Coliseum. Like the new landowners they were, the Dodgers had to wait for their stadium to be built. They’d expected to play at the Rose Bowl, but when that didn’t pan out, they moved on to the 1923 Coliseum, built for football but adaptable enough for the 1932 Olympics and later four seasons of major league baseball.

And then, the Dodgers, now the Los Angeles Dodgers, swept all before them — and, once, even a World Series.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.