Why was there an alligator farm at Lincoln Park? It was one of many odd amusements of L.A.’s past

- Share via

Through our months of COVID cabin fever, at least we can take some pleasure in fantasizing about what we’re going to do once we get off pandemic parole.

Long before Disneyland — even before Walt Disney moved here, in the summer of 1923 — Angelenos had the choice of dozens of themed mini-amusement parks right here.

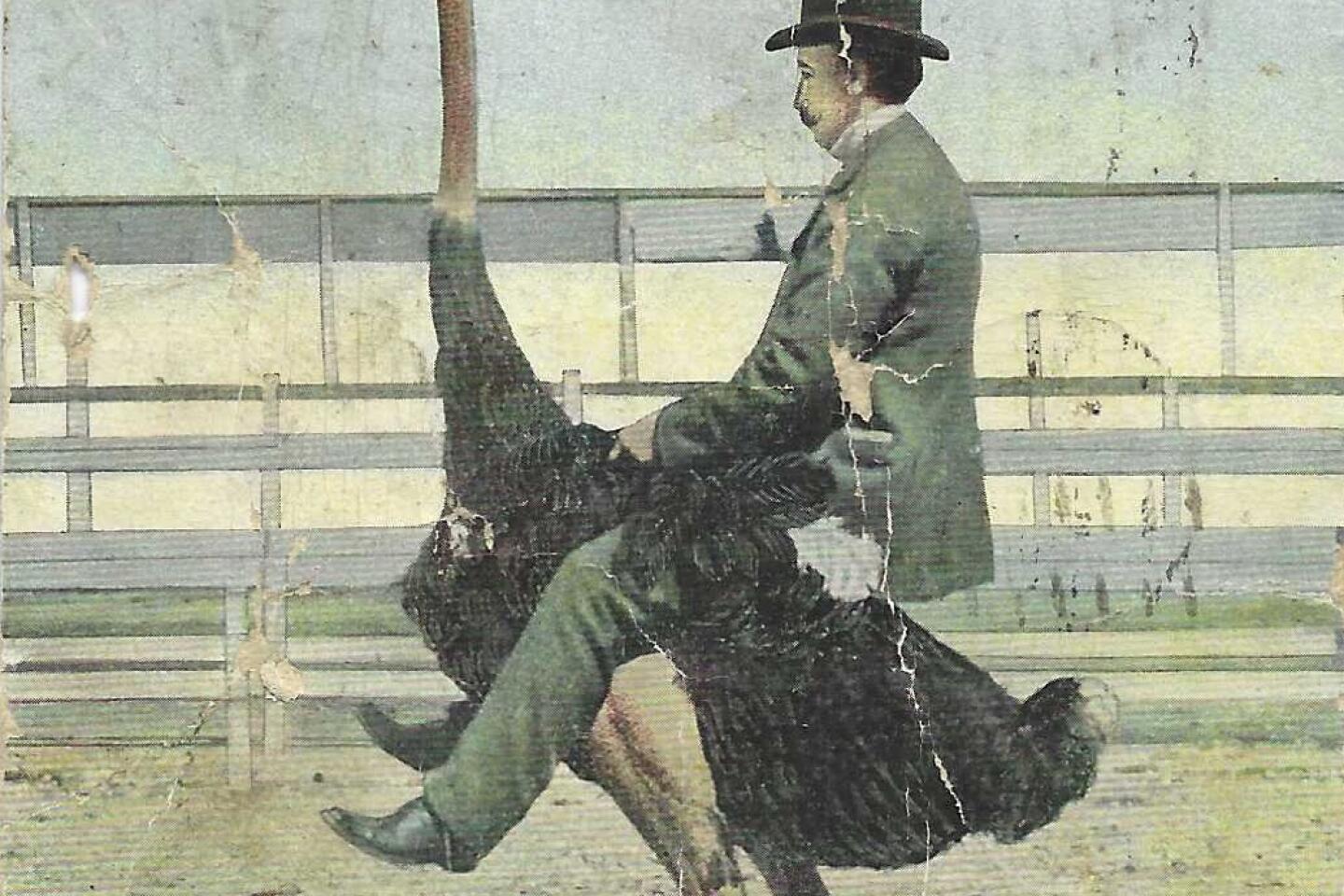

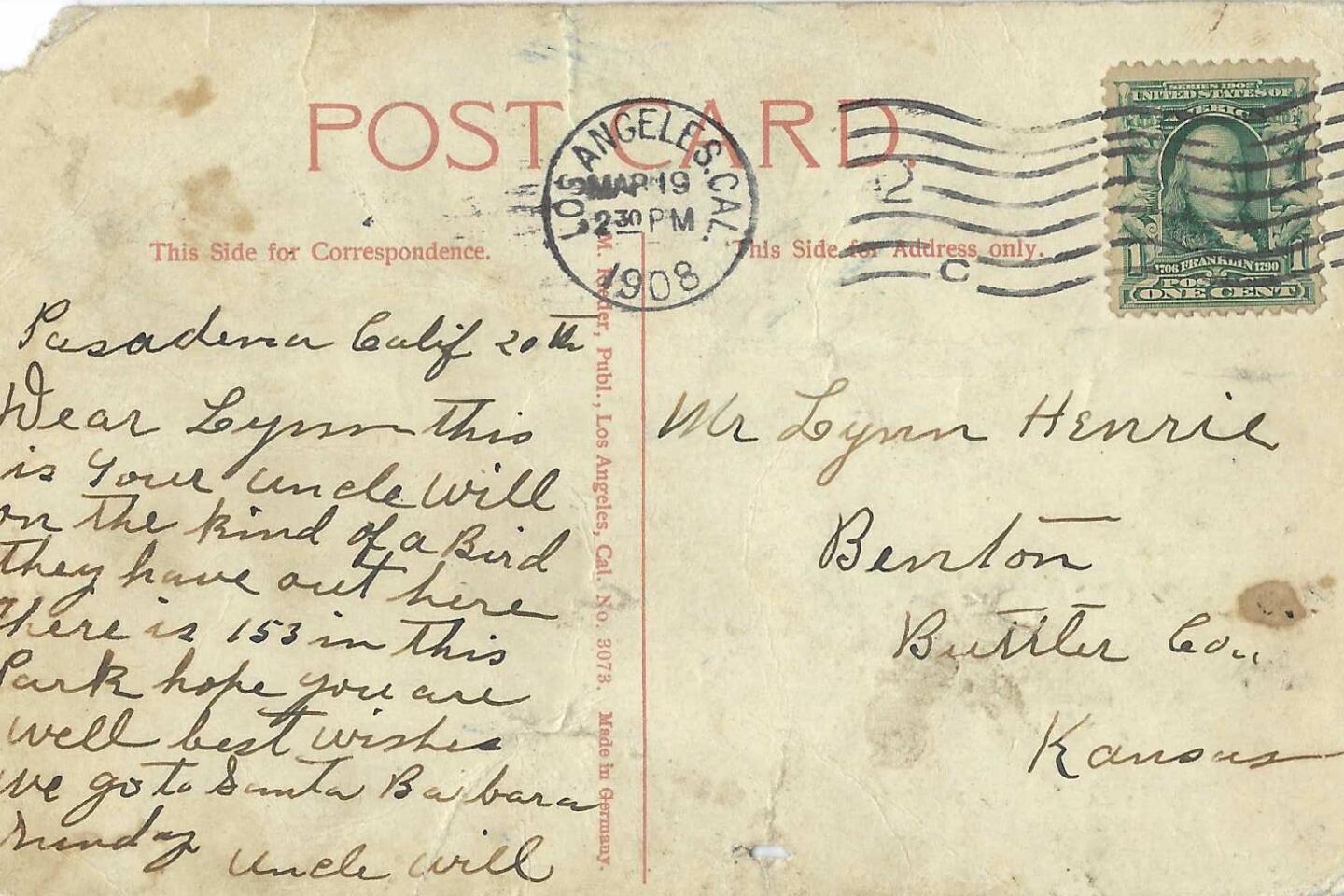

In carnival L.A., you could visit not just one but two ostrich farms, not just one but two private zoos, a monkey farm in Culver City and another in the Cahuenga Pass, and at least two lion farms: Jungleland, originally Goebel’s Lion Farm, in Thousand Oaks, and Gay’s Lion Farm, in El Monte, the place that MGM’s trademark snarling lions called home.

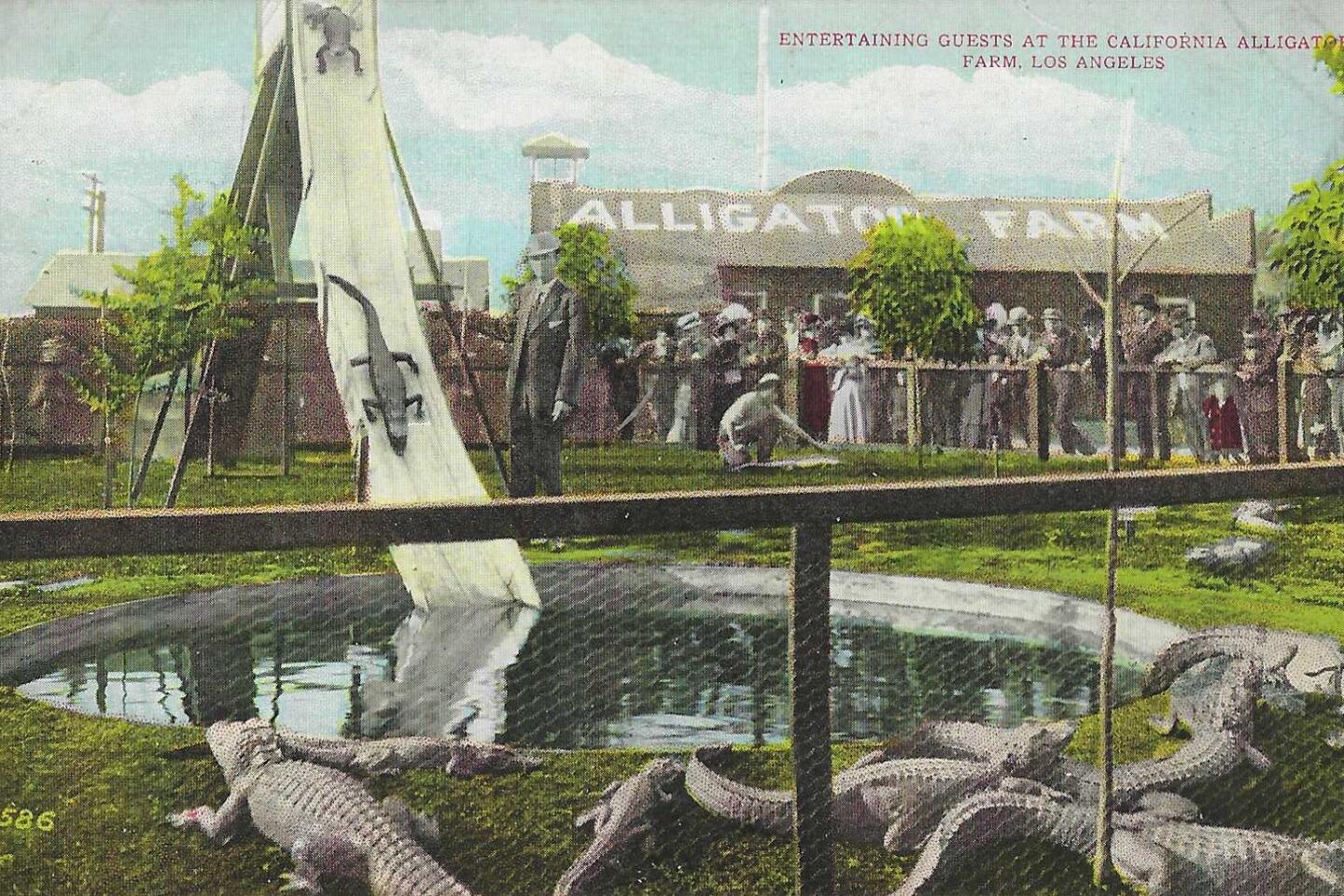

Roller coasters galore, Ferris wheels, merry-go-rounds, hot-air balloon rides, an alligator farm in Lincoln Park that was a goldmine for headlines like “Gators Now Hatching—Good For Pets or Bags!” and “Saved From Death In Alligator’s Jaws!”

Let’s just say that zoning rules were a little more flaccid back then.

You, constant readers, have asked about amusements of fresher memory — Beverly Park and Ponyland, the kiddie cars and pony rides at Beverly and La Cienega, a modest childhood adventure-land where the Beverly Center now welcomes large cars and sells pony-hair shoes.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Here you have an answer from Zev Yaroslavsky, the former Los Angeles County supervisor and one of Beverly Park’s devotees, when I asked him to go full-on nostalgic:

“I used to go to Beverly Park for my birthday every year once we moved from Boyle Heights to the Fairfax area.” When developers bought it all up to tear it down, “I was crushed. ... I actually tried to persuade the Beverly Center developers to put the pony ride on the roof of their shopping center, but they couldn’t get the county health department to approve it because the restaurants were right below the roof.

“I never bought that explanation, but I had no leverage at the time to arm-wrestle them.”

What killed off all of our pleasure piers and wild animal grounds?

First, real estate prices — the easy-lucre allure of selling five-to-an-acre houses instead of five-for-a-buck admission tickets.

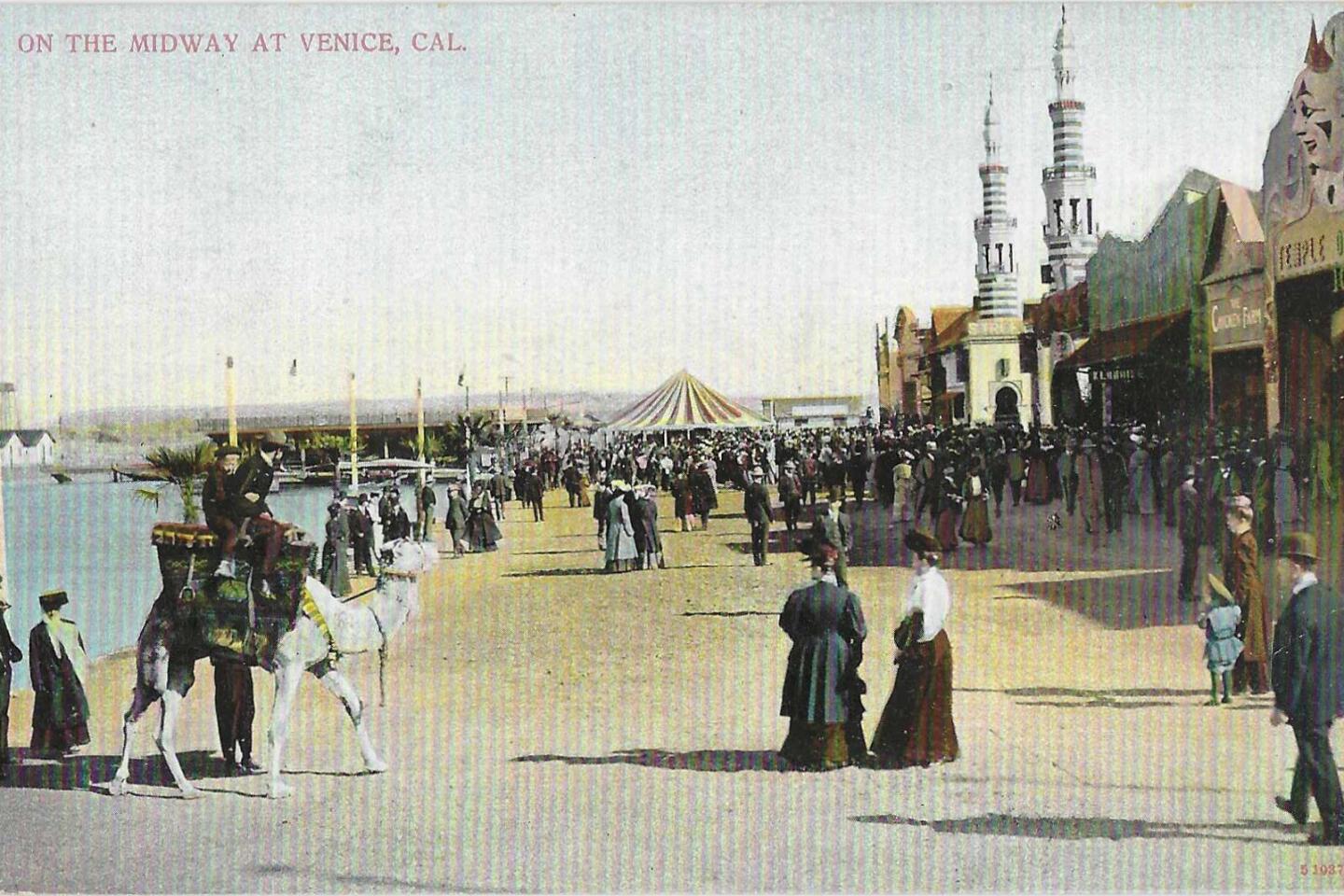

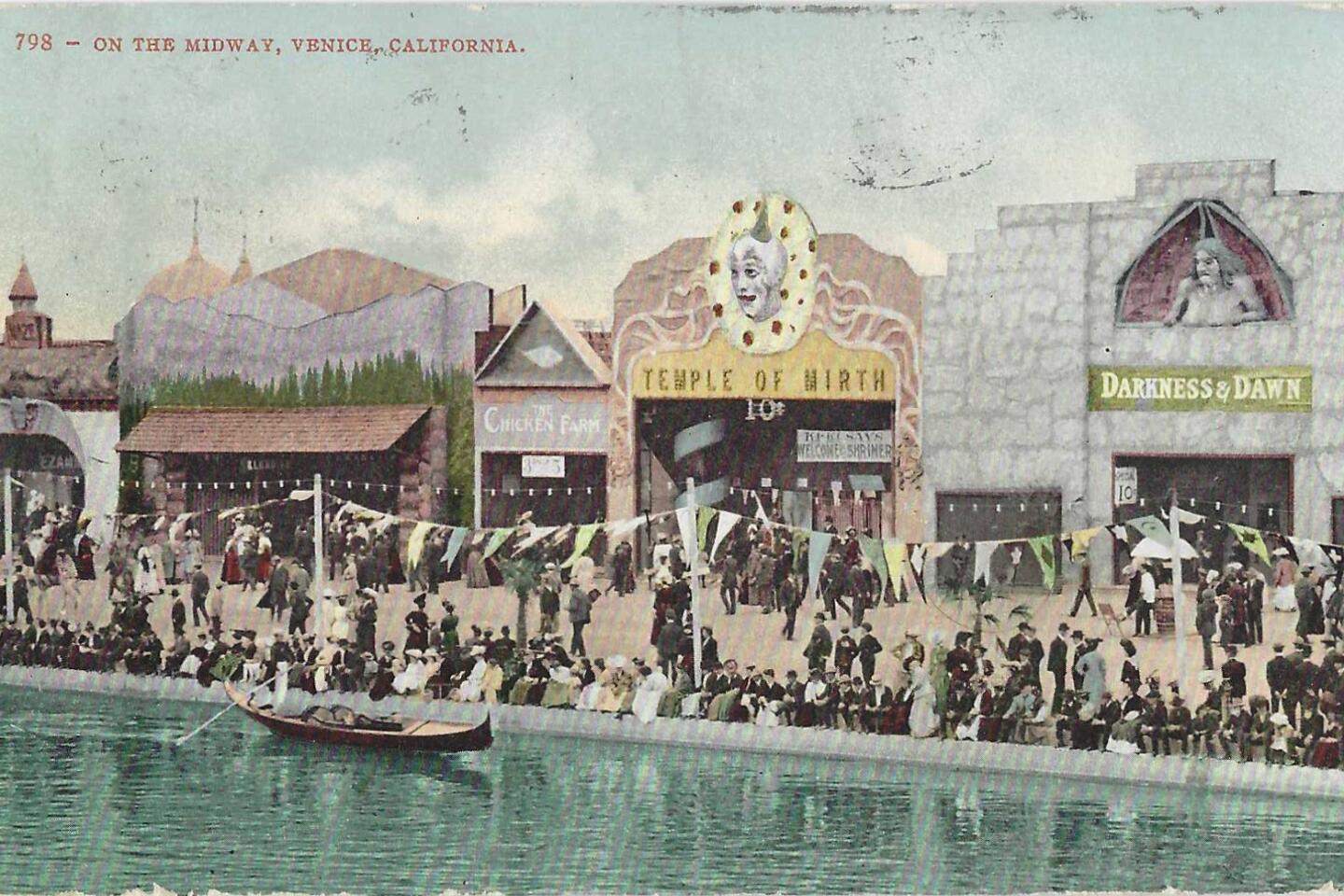

Second, fires. Those legendary coastal fun piers of Venice and Santa Monica were wonders of imagination and thrills, but they went up in cinders more often than old Moscow. The last of them, the sea-meets-space-age Pacific Ocean Park, opened in Santa Monica in 1958, but it didn’t burn until after it closed nine years later.

Third, liability. That Lincoln Park alligator haven wasn’t exactly watertight. Some of its thousand bellowing saurians got used to moseying around the Mission Road neighborhood when floodwaters rose high enough to float them free. But after World War II packed L.A. with yet more people, the new families in their new homes got quite agitated at the thought of their baby-boom babies becoming gator bait. So the farm upped sticks for Buena Park in 1953, but that gig closed down in 1984.

Less festively — as “Pets or Bags!” promised — the animals were treated like a crop of corn.

They were rented out to movie productions, which until 1939 didn’t have even the merest humane guidelines. Those cute silver foxes you could visit at the farms of Mt. Lowe were skinned for flappers’ fur collars. The ostriches of South Pasadena gave rides to bolder tourists, laid amusingly enormous eggs, provided plumes for fans and hats, and gave up their lives for wallets and belts.

Grider’s Birdland aviary on Central Avenue near downtown sold visitors both tickets and birds. Leroy Grider died in 1919, a few years after providing another public entertainment: his divorce case. His wife said Grider habitually drank himself silly, left the house to attend funerals of people who weren’t dead, and came back wearing a different suit from the one he left home in. The judge wasn’t buying it.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

Do not roll your eyes at these guileless pleasures. Remember that Los Angeles was a long way from more sophisticated cities, that the wide world, so full of the exotic, was an expensive place to visit, so these were marvels indeed.

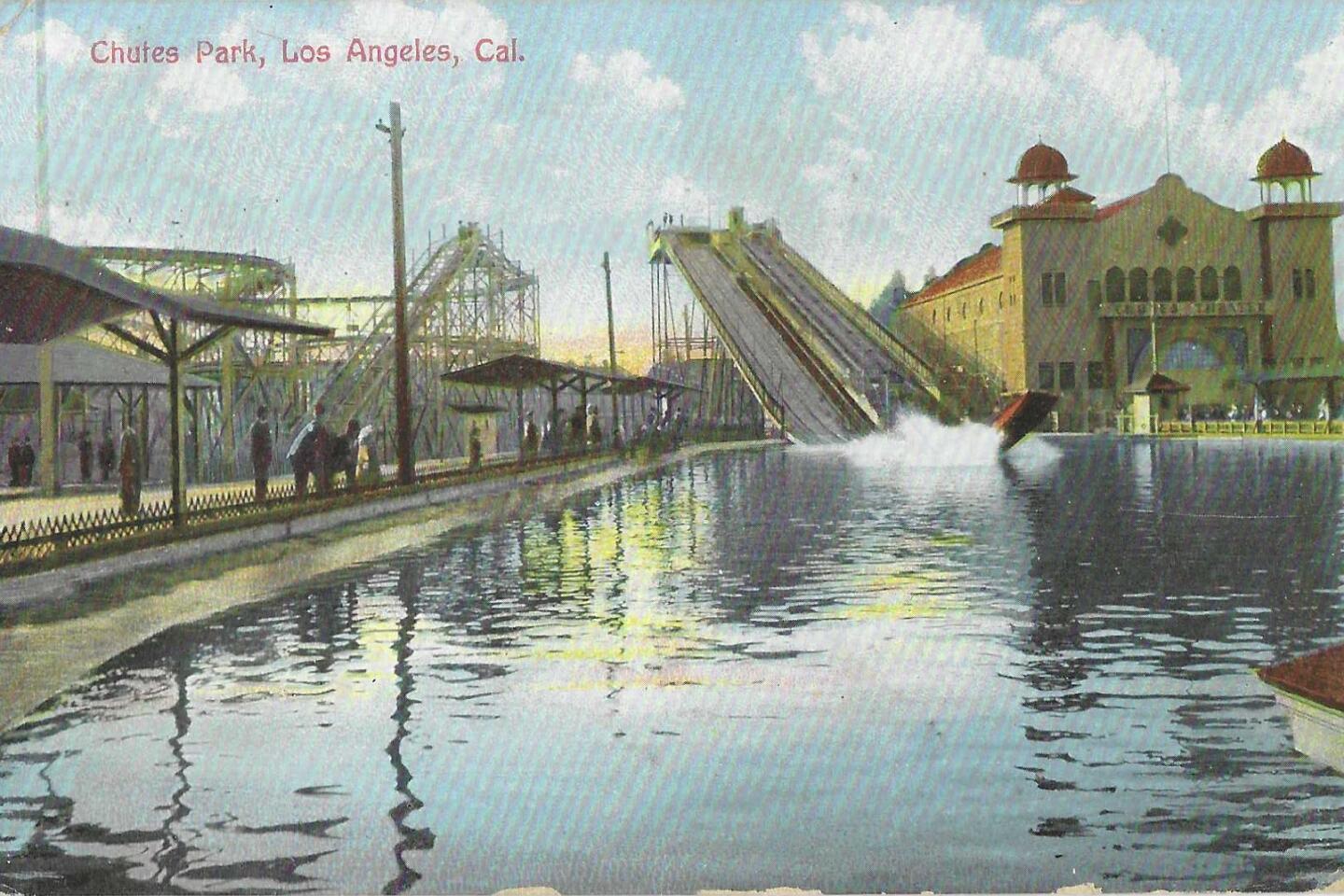

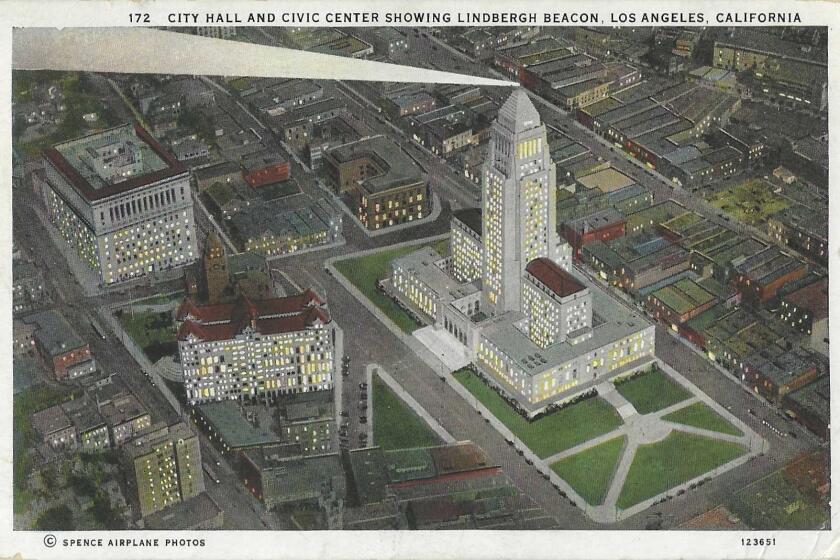

The most magnificent and magical — the one that makes you yearn for an afternoon of time travel — stood on 35 acres of farmland bounded by Grand and Main, Washington and 21st Street below downtown. It went first by the name of Washington Gardens, then Chutes Park, and lastly Luna Park.

Over its 30-some years of life, it found time and space for political speechmaking and club picnics, a lighted electric fountain, an orchestra of 50 playing opera selections, German beer and Japanese tea gardens, a genius horse and a monkey circus. Beautiful-baby contests regularly left one triumphant winner and 19 seething mothers.

Decorous ladies shrieked their way down the water toboggan “chutes.” Billiken’s Temple of Mirth and Joyland delivered G-rated guffaws. The Civil War ironclads Monitor and Merrimack did miniature battle on a manmade lake. Hundreds could bowl, a thousand could watch Vitascope “flickers,” and 10,000 fans could cheer the Los Angeles Angels playing Pacific Coast League baseball.

In 1901, “Chinese Day” at the Chutes welcomed hundreds of people archly called “celestials.” This was no paragon of progressive thought. No citation can be found for days devoted to other nationalities or ethnic groups. And although the vast acreage was sold in 1912 to investors who made noises about creating a park for the city’s African Americans, nothing came of it, unsurprisingly, and by 1914, the park’s skeletons were being dismantled for yet more development.

What almost all of these places had in common is that they were designed with decidedly nice people in mind — good, hardworking Angeleno families. Not for L.A. the unsavory enticements of East Coast midways.

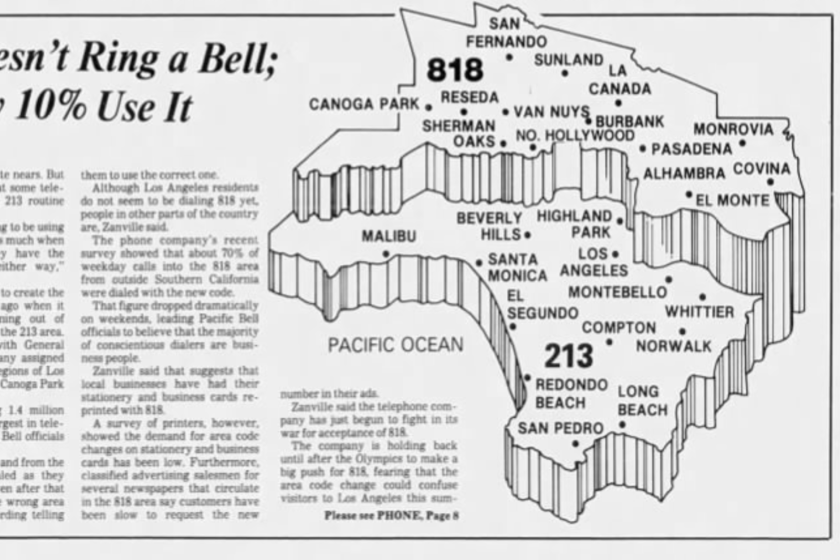

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

So what a gas that one straggling remnant of this age is in the footprint of the old Long Beach Pike, which stood along a stretch of coast where you can now find the Aquarium of the Pacific, shopping and a Ferris wheel.

The Pike opened in 1902. It survived makeovers and as many peaks and plunges in status as a boardwalk roller coaster. The honky-tonk vibe of tattoo parlors and girlie joints catering to the shore-leave crowd helped the city decide in 1979 not to renew its lease.

The Pike had one last “boo!” left in it. In 1976, someone moving what he thought was a red-painted funhouse dummy found himself holding the detached arm of a real, mummified man.

Elmer McCurdy had been the worst train robber in Oklahoma. He blew up a safe filled with $450 in silver coins, most of which melted and stuck to the safe. In 1911, his last stick-up — mistaking a passenger train for a freight train carrying $400,000 — yielded a humiliating $46, some whiskey and the conductor’s watch.

The law quickly caught up with him, and when he was shot dead, he was, again humiliatingly, prone, and drunk. His unclaimed corpse began its 65 years of wandering through carnivals and sideshows. McCurdy now lies buried on Boot Hill. It’s the one in Guthrie, Okla., not the one at Disneyland.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.