- Share via

HANFORD, Calif. — At an Elks Lodge in the Central Valley, Larry Faria stood before a grassroots conservative group called the 1776 Sons of Liberty and asked for a show of hands.

It was Monday night, a few hours after U.S. House Republicans passed a set of operating rules for the new Congress that included concessions Kevin McCarthy made to the hard right during the historic 15 rounds of voting it took for him to become speaker.

“Raise your hand if you think we stood our ground for valuable concessions,” Faria asked.

Hands shot up.

“Raise your hand if you think it should have been a status quo vote for McCarthy.”

None rose.

Sure, McCarthy is the hometown guy from Bakersfield, representing the rural, agricultural Central Valley.

But the divides that have rankled the national GOP, humiliating McCarthy and temporarily stalling his long bid for the speaker’s gavel, are palpable in his reliably red district, which became even more conservative after congressional maps were redrawn in 2021.

Mainstream Republicans here are thrilled by McCarthy’s ascension and the spotlight it shines on the Central Valley, where conservatives have long complained about being drowned out in halls of power by urban liberals.

“Kevin is a fighter, and he wants to move the country forward,” said Assemblyman Vince Fong (R-Bakersfield), who worked for McCarthy for a decade. “He will be a tremendous advocate for the Central Valley and all Californians to get our country moving in the right direction, stopping inflation, stopping overspending, advocating for hardworking families, dealing with the border.”

David Bynum, a Bakersfield lawyer and former intern for McCarthy, said most local conservatives are excited to have one of Kern County’s own as speaker.

“Anyone that knows him knows he’s a likable guy,” Bynum said. “He knows your kids’ names. The last time I saw him, he was at a bakery in town getting a doughnut. He comes across as down-to-earth, local guy.”

But McCarthy’s embarrassing saga was cheered on his home turf by a vocal contingent on his right, who accuse him of being a RINO — Republican in Name Only — more concerned about personal power, Washington politics and fundraising than serving the Central Valley.

“I have not heard one person say this was a shame, or a sham, or that it should have never happened. Not a one,” said Greg Perrone, president of the Greater Bakersfield Republican Assembly, an activist group he compared to the hard-right House Freedom Caucus.

He said McCarthy represents an establishment GOP that held both Senate and House majorities during the first two years of the Trump administration, and “the agenda they got accomplished was zero.”

Representatives for McCarthy did not respond to requests for comment.

As the state GOP has lurched rightward, its influence has plummeted. Gone are the days of California sons Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon, who were centrist by today’s standards.

Republicans have not won a statewide contest since 2006, when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger was reelected and Steve Poizner became insurance commissioner. Among California’s 22 million registered voters, Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 2 to 1.

McCarthy’s rise has been one of the few bright spots for state GOP officials, who hope McCarthy — a skilled fundraiser — will bring money and clout to the 11 other California Republicans in the House.

“He has been the most important and powerful Republican in California for at least the past decade. If he’s speaker, that’s good for [California] Republicans,” said Rob Stutzman, a longtime GOP strategist.

Tim Miller, who worked for the Republican National Committee and left the party after the 2020 election, said he is skeptical that McCarthy will be able to deliver anything meaningful for California because of Republicans’ razor-thin House majority and the dysfunction in Congress.

In California, he said, the GOP “has continued to look more and more like the ... objectors than it has like Kevin McCarthy.”

Despite the state’s sapphire tilt, more than 6 million Californians voted for then-President Trump in 2020 — more than any other state in the nation.

The twice-impeached former president remains popular in McCarthy’s Congressional District 20, which stretches from Bakersfield north to Hanford and Clovis.

Oil and water dominate local culture and politics. Along Highway 99 south of Hanford, a billboard begs, “Pray for Rain,” next to a drought-plagued orchard with ripped-up trees. Other billboards lambaste Gov. Gavin Newsom for not building more dams. At the Kern County GOP headquarters, an oil pump jack stands in the parking lot.

In the district, Republicans hold a 19-percentage-point voter registration advantage over Democrats — the largest gap in the state.

Still, the Central Valley as a whole is changing. Some districts, once reliably red, are becoming increasingly competitive, as the region becomes more Latino and less Republican.

In a district next to McCarthy’s that contains the southern chunk of Hanford, Republican Rep. David Valadao won a tight race in November and had lost the seat to a Democrat four years earlier.

McCarthy should not take his voters for granted, Perrone said.

“For far too long, Kern County Republicans have sat back and said, ‘We’re safe here. We’re conservative,’” he said. “By and large, the vote tends to show that that’s still the case, but to me, it’s like there’s a warning: There’s smoke over there behind that wall, and maybe you need to look and see if it’s actually on fire.”

In his acceptance speech, delivered after midnight, McCarthy quoted country music legend Buck Owens: “How many of you that sit and judge me ever walked the streets of Bakersfield?”

“Well, I’ve walked those streets,” McCarthy said. “I know its people. They are hardworking and relentlessly optimistic about our future.”

Bakersfield has long been one of the reddest cities in California. It attracted Dust Bowl refugees who came to work in the fields and brought their conservative, deeply religious views with them. And it is the birthplace of country music’s gritty “Bakersfield sound” and home to one of its patron saints, Merle Haggard.

McCarthy, 57, has deep roots in the city. The son of a firefighter, he played football for the Bakersfield High School Drillers and ran a sandwich counter called Kevin O’s out of his uncle’s yogurt shop.

The McCarthy business in a strip mall on Stine Road is long gone, replaced by Pollos a La Brasa, a Peruvian restaurant next to a massage parlor. There, most patrons said they weren’t paying close attention to — and didn’t care about — the drama in Washington.

At a disc golf course near McCarthy’s field office and the dry Kern River bed, a man in a sweatshirt depicting a fetus and the words “Equal Rights for All Humans” called the speaker votes “a clown show.”

The 45-year-old hospitality worker, who declined to give his full name, described himself as an “abolitionist” who wants to criminalize abortion as homicide. He said he regretted having previously voted for McCarthy, whom he called “bought and paid for” by lobbyists.

“RINO!” one of his friends chimed in.

In Hanford, where the smell of dairy cows hangs in the air, Adam Medeiros called the McCarthy vote saga “a wonderful process of checks and balances.”

Medeiros, a conservative hair salon owner and school board member, ran against his friend Valadao — whose hair he has cut for years — in last year’s June primary. Medeiros said he, like many here, felt betrayed by Valadao’s vote to impeach Trump after the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Redistricting sliced Hanford in two, and Medeiros ended up on McCarthy’s side of the line. That didn’t stop him from running against Valadao, because House members aren’t required to live in their districts.

McCarthy is a “career politician” who no longer understands “society and how it functions,” Medeiros said.

Did he vote for McCarthy?

“That’s a private question,” Medeiros said, laughing. “But, yes, I did. I still believe that he was better than the Democratic challenger.”

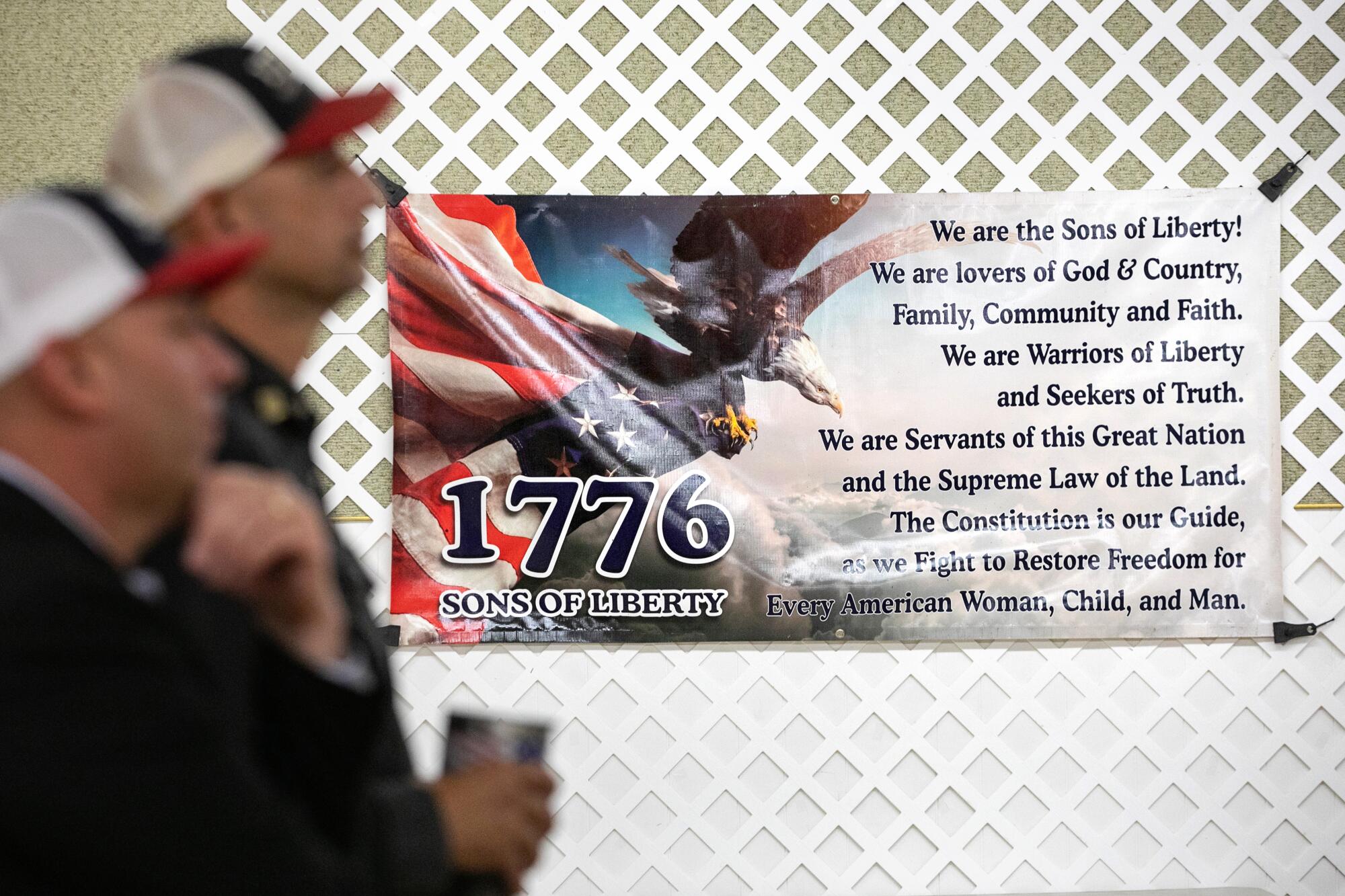

There was no love lost for McCarthy at the 1776 Sons of Liberty gathering in Hanford, where a banner with a bald eagle and American flag read: “We are lovers of God & Country, Family, Community and Faith.”

Dozens gathered during a welcome rainstorm to hear the conservative new Kings County district attorney, who decried California laws that reduce prison sentences.

In the audience were cops and farmers, two Hanford city councilmen and a man wearing a shirt that said: “I’m 1776% sure liberals hate me.”

“I dislike Kevin McCarthy immensely,” said Jeffrey Mora, the group’s former president and a field coordinator for the John Birch Society. “He’s not a conservative. I believe he’s heavily influenced by globalist policies and in the pocket of lobbyists.”

Mora passed out pamphlets from the John Birch Society rating McCarthy’s votes on various issues. He was deemed “unconstitutional” for supporting aid to Ukraine and “constitutional” for opposing federal gun control measures.

Faria, a public safety worker and the Sons of Liberty’s president, said he had little faith that a Speaker McCarthy would bring more resources to the Central Valley.

McCarthy, he said, “talks a big game” on issues like water infrastructure and storage, “but we haven’t seen results.”

“We haven’t seen any new dams, the groundwater is getting pumped out and not being replenished and replaced. ... The lakes are still empty.”

The crowd cheered the congressional holdouts who put McCarthy through the wringer, then turned its attention to what it said was an urgent local issue: debate over a new traffic roundabout.

Branson-Potts reported from Hanford and Bakersfield, and Mehta from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Melanie Mason contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.