As Kevin McCarthy’s California district gets redder, discontent brews on his right

- Share via

CLOVIS, Calif. — In Washington, Kevin McCarthy is the ultimate party-line Republican, one of former President Trump’s most loyal congressional foot soldiers and leading the charge in the GOP’s quest to regain control of the House in November.

But back home in his district, Cora Shipley is skeptical.

“I do not believe that he is a true conservative,” said Shipley, 78, owner of an ice cream shop in Clovis, which was drawn last year into the new 20th Congressional District, where McCarthy is seeking reelection.

Shipley’s shop is a staple of Old Town Clovis, where American flags line antique stores and country music plays over a loudspeaker. She said she is waiting to see how McCarthy will lead the GOP should he become House speaker next year.

“He’s been on both sides of a lot of issues,” she said from a table in the back of her shop, with photos of Elvis on the walls and a “thin blue line” flag hanging outside.

McCarthy is tasked with introducing himself to more than 200,000 new voters in a district where the GOP’s registration advantage has grown to almost 20 percentage points, the largest in the state. But even in an area that red, McCarthy faces mistrust from voters on his right flank — including some who have supported him in the past.

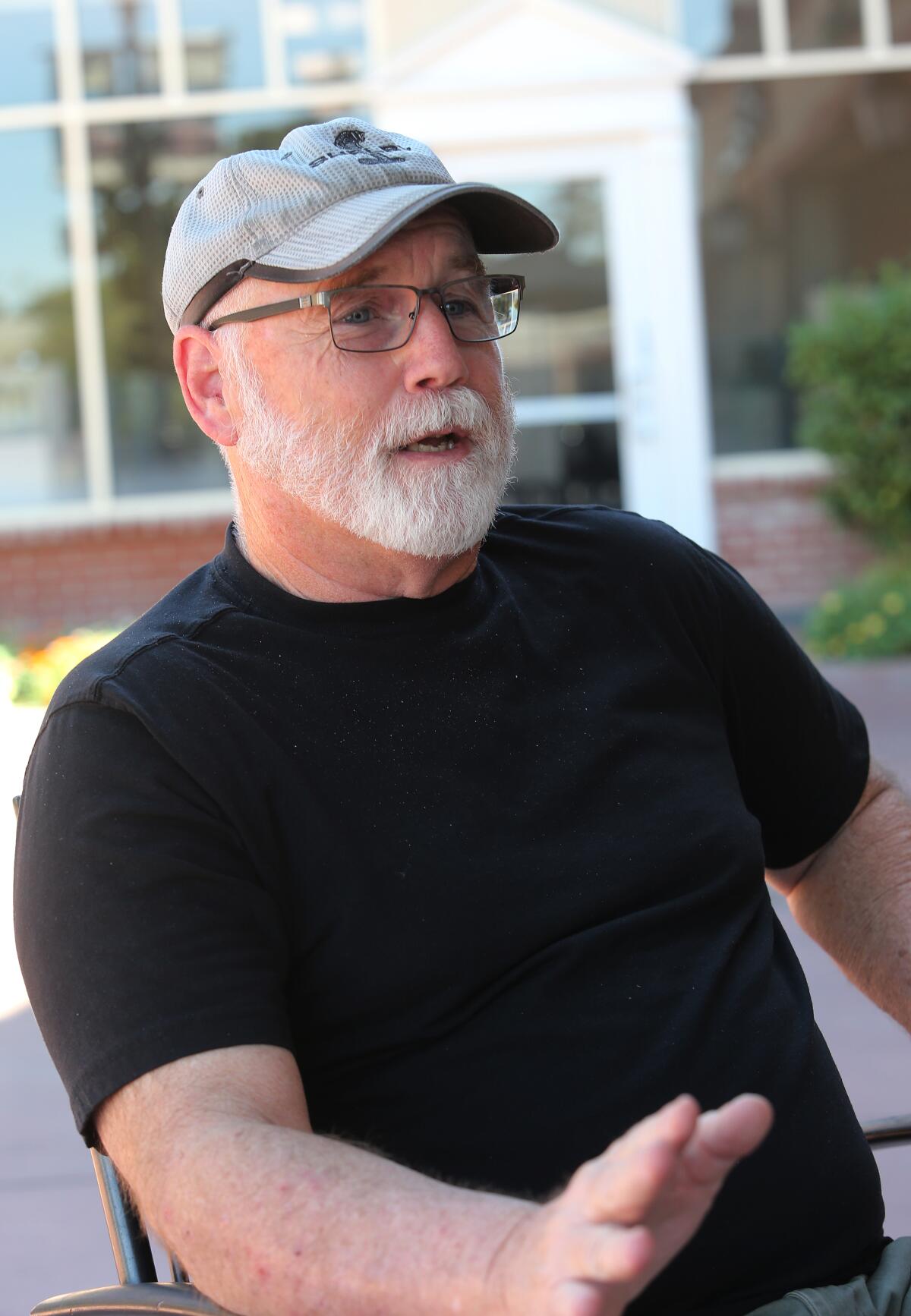

“When you hear people talk about the swamp, he’s part of that system,” said Eric Rollins, 57, of Clovis. “He’s a long-term politician.”

The 20th District covers part of California’s San Joaquin Valley, awkwardly clawing to the west in its northern half to include Clovis and some of Hanford — both solidly red areas that are new to McCarthy. Much of the district, however, is familiar to the eight-term Republican: It draws almost a quarter of its population from his hometown of Bakersfield, the largest city in Kern County, where oil jacks bob alongside roadways and temperatures many days top 100 degrees.

Only two hours north of Los Angeles, Bakersfield is the gateway to the red island that some Californians view as flyover country. Here, agriculture and oil dominate the culture and, in turn, the conservative politics. It’s a region that is “more west Texas than Texas,” said Mark Arax, a journalist who has written extensively about it for The Times and others.

McCarthy, 57, is generally popular in Bakersfield, thanks in part to his deep roots in the city: He ran a small sandwich shop after graduating from the public high school, and his father was assistant fire chief. Supporters say McCarthy has a strong conservative record in Congress, and many are excited about the possibility of one of Kern County’s own serving as speaker.

“I don’t know one issue that Kevin McCarthy has voted on in Congress that a conservative wouldn’t respect,” said Cathy Abernathy, 71, a Kern County Republican consultant. When she was chief of staff to GOP then-Rep. Bill Thomas, she hired McCarthy as an aide.

Even with a reshaped district, Abernathy said, “the basic issues don’t change — it’s the economy, it’s education, it’s transportation.” Locally, some hope McCarthy’s stature in Washington will help slow down environmental regulations that threaten the region’s oil industry, she said.

Others in the area back him based on his good reputation. He’s known as “a first-name-basis kind of guy,” said Jan Scurlock, a 70-year-old former financial consultant who moved here four years ago. She plans to vote for McCarthy in November.

But the low level of trust conservatives have in institutions and government is palpable in the district — and its manifestation isn’t always friendly to McCarthy, who has served in Congress since 2006.

“I’m not sure if I can trust that he’s going to do exactly what he’s saying,” said Ronnie Martinez, a 51-year-old sales representative from Bakersfield.

Martinez leads a weekly Bible study outside a shopping center, where attendees expressed mixed feelings about the congressman.

“I think he’s kind of a marshmallow,” said Scott Cross, 65, a music instructor. “I used to like him a whole lot. But he’ll back this, and then when it’s unpopular to back this, he’ll back that. And when it’s unpopular to back that, he’ll back this.”

With California’s primary over, the focus turns to the state’s role in the battle for control of the House of Representatives in the general election.

McCarthy has proved to be a staunchly conservative leader of the House GOP caucus. Still, some voters remain unsettled by his momentary denunciation of Trump’s part in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. Others say McCarthy simply has become too comfortable in Washington, where the focus is always on the next election. The anger often seems fueled by conservative media, and many of McCarthy’s right-wing skeptics are influenced by misinformation, espousing false theories about fraud in the 2020 election.

“He’s a snake,” said Greg Williams, 65, a retired California Highway Patrol officer from Bakersfield who is quick to qualify that it’s not a McCarthy problem so much as a Washington problem. “I don’t trust any politician,” he said.

At a shaded table outside a Starbucks at a Bakersfield shopping mall, where Williams gathers each afternoon with a few mostly retired friends, his peers agree.

“I just wish somebody else would run against him,” said Richard Tidwell, 68, a retired veteran. “Everybody in there is corrupt.”

Back in Clovis, Shipley is waiting to pass final judgment.

“I want him to tell the truth, and I want him to stand behind the conservative wing of the Republican Party,” she said.

McCarthy can count on support from most of those who are distrustful of him — if only because they have nowhere else to go.

“Look at the alternative,” Tidwell said, referring to Democrats.

For years, the district’s dark-red makeup has shielded McCarthy from serious political threats — a trend that almost surely won’t change in November, when he’s on the ballot against Democrat Marisa Wood, a public school teacher. He has easily fended off primary challenges, including in June, when he earned 59% of the vote.

His response to the 2020 election has pushed some moderate voters away, but even they acknowledge that it’s not a large enough bloc to be politically meaningful.

Dale Pitstick, 60, a lifelong Republican whom Trump turned into an independent, winced when asked whether he’d voted for McCarthy in the past. “An error,” he said.

In Bakersfield, “people are still entrenched in Trump world,” said Pitstick, who works for an insurance company.

Rep. Liz Cheney said at California’s Reagan library that the Republican Party cannot be loyal to both Trump and the Constitution: ‘We must choose.’

To him, McCarthy’s continued embrace of Trump after the Jan. 6 attack “uncovered who Kevin McCarthy really was.”

“He’s a power-hungry individual who’s out for himself,” Pitstick said, “not for the citizens.”

Thomas, the former Bakersfield congressman who mentored McCarthy, also sharply criticized his successor after Jan. 6, saying on a local talk radio show that he “put politics ahead of country” and perpetuated lies about election fraud.

McCarthy, whose campaign did not respond to requests for an interview, backed a failed legal effort that would have overturned the 2020 election and later voted against certifying results from two states. After the Jan. 6 insurrection, he condemned Trump’s behavior, saying he “bears responsibility” for the attack, and acknowledged Joe Biden as the winner.

McCarthy has been featured prominently in the House committee hearings investigating the events of that day. In a prime-time hearing Thursday, the panel played previously leaked audio recordings in which McCarthy said Trump should resign.

But he has continued to embrace Trump since then and refused to answer a question last month about whether Biden was the legitimate winner of the election.

GOP divisions continue over the RNC censure of Reps. Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger with a resolution that seems to minimize the Jan. 6 Capitol attack.

McCarthy’s district in California has seen sharp demographic changes in recent decades — it is now more than a quarter Latino — but that hasn’t posed a problem for him.

David A. Torres’ mother used to say that if you were born Latino, several things were a guarantee in life: “You were a Democrat, and you were Catholic” — and you rooted for the Oakland Raiders.

“Things have changed significantly from that,” said Torres, a 61-year-old Bakersfield-based defense attorney who once considered running against McCarthy as a Democrat. “Just because you’re Latino doesn’t guarantee that you are going to be a Democrat.”

The GOP’s efforts to label Democrats as “socialists” and “communists” have been effective with many Latino voters, he said, and abortion remains a sticking point for some.

But to Rollins, a grass-roots political activist in the Clovis area who hosts a talk show on AM radio, those terms aren’t just Republican mantras.

“I truly believe there’s a rise of authoritarianism,” he said. “You can call it socialism; you can call it communism — but it’s a rise of authoritarianism. They believe that the state should be telling you what to do.”

Rollins said he would be inclined to back a conservative challenger to McCarthy if a viable candidate were to emerge.

His most important issues: the economy, “protecting 1st and 2nd Amendment” rights and immigration. The 2nd Amendment, he said, “is a backup for when politicians decide that we no longer have rights.”

Is it coming to that?

“We’re not there yet — it could,” he said. “Hope not.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.