L.A. has been enthralled by car chases for about as long as we’ve had cars on roads

- Share via

Come on — you know you watch them. We all do now and then, even if it’s just because we happen upon one while spinning the channels.

Thirty or 40 seconds in, we’re hooked. And then we’re stuck taking the ride to the end, whatever that turns out to be: until the chase ends, until the newscast ends, or until we feel disgusted at having fallen for it again and change the channel.

The televised real-time police chase — writer Mary Melton, in Los Angeles magazine, once called it our “longest-running reality series.”

Last Friday night, just in time for the 10 o’clock news, a bold motorcyclist owned the airwaves as he raced along streets and highways in Eagle Rock, Glendale, Burbank, Hollywood, skirting the Los Angeles River, into Universal Studios. Once, he appeared to lose a shoe and stopped to put it back on.

Like Harrison Ford trying to blend into a parade to dodge pursuers in “The Fugitive,” this man briefly rode among a group of other motorcyclists to try to throw off the cops. He insolently stopped to gas up his bike. He may have ditched his ride in a garage at the Grove and made a getaway. For all we know, he may be getting an agent right now to sell the story rights.

These chases mostly end meekly, sans gore or gunfire, with a peaceable arrest following a certain time-plus-mayhem factor. That’s why you may search in vain for any news stories the next day, and it ticks you off: You invested how much time? Ten minutes? Twenty? In watching this thing that in the end wasn’t newsworthy? It’s like junk food: You open the sharing-size chips bag and a half-hour later the bag is empty and you wonder just how you ended up eating it all.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

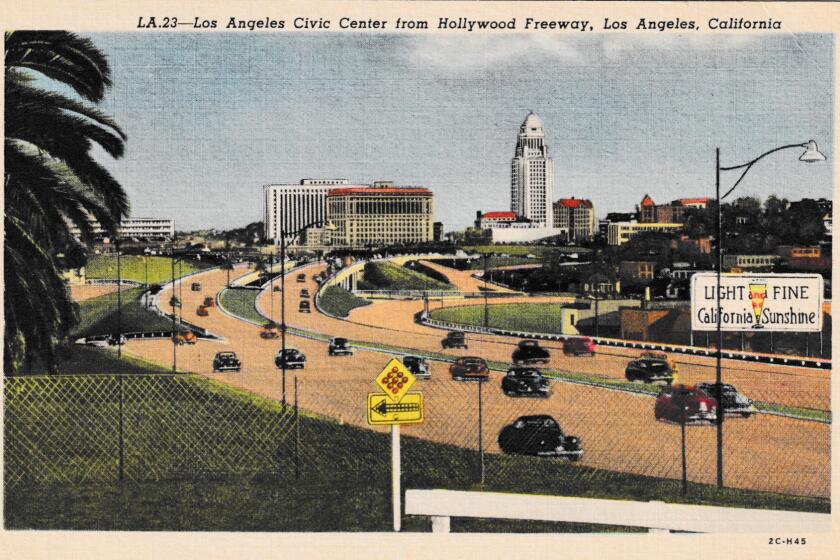

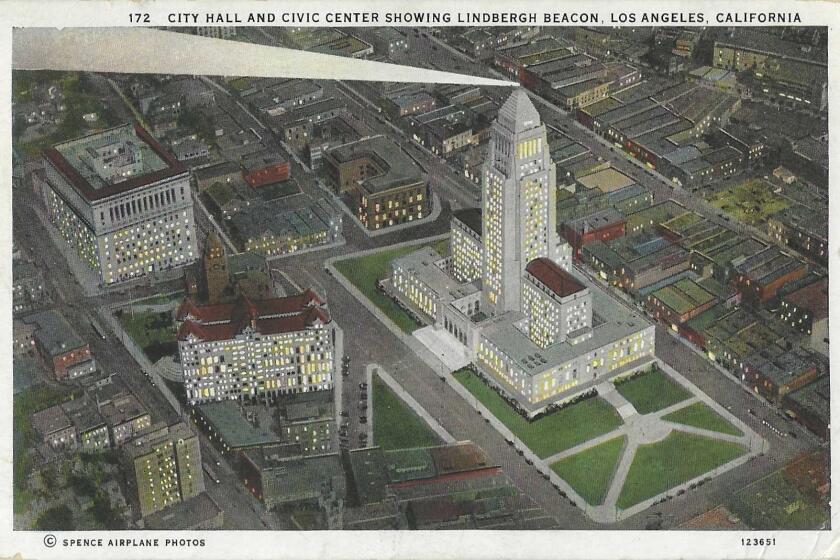

Our longest-running reality series is longer than you’d think. Before TV helicopters, before O.J., before TV, even before radio, L.A. speeders have spent about 120 years racing along Los Angeles’ enticing roadways, and the cops have spent as many years chasing them. The natural and built landscape that once made us the nation’s bank robbery capital — the vast, flat valleys, the freeways and avenues and onramps, the patchwork of police department jurisdictions — also makes it the ideal temptation for racing the cops.

So you can’t entirely blame movies for lead-footed Angelenos and the notoriety they came to acquire when the glare of publicity and later of the roving aerial spotlight fell upon them. We were already out-accelerating the cops years before Mack Sennett’s “Keystone Kops” were careering around the hills of Edendale, and before the “Fast & Furious” franchise made it look enthralling.

And in a place that has no weather to speak of, our conversational ice-breaker is traffic, so any warps and breaks in ordinary traffic naturally catch us up in them.

The city put in speed limits around 1904, and the Automobile Club urged its members to obey them. As if.

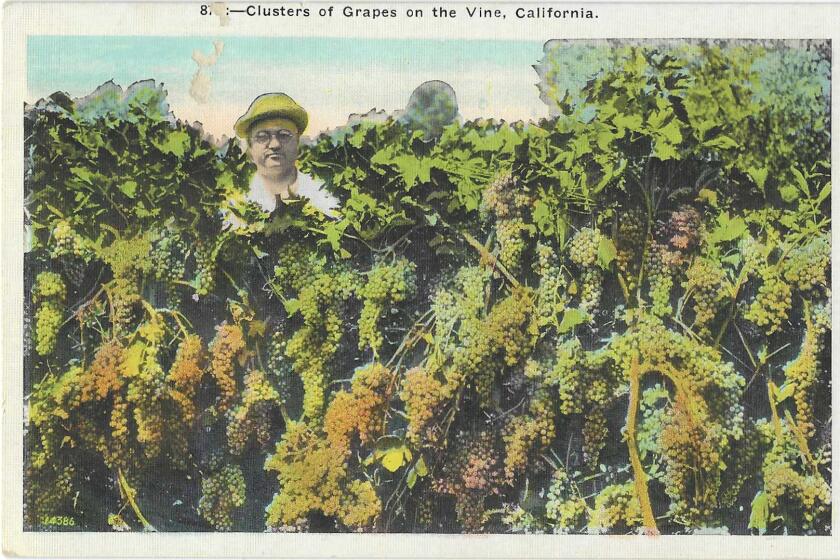

Next time you raise a glass of California wine, remember the time when Los Angeles, not Northern California, was the state’s major wine region.

In February 1905, M.T. Hancock, a multimillionaire manufacturer of plows, was in court, exhorting his poor chauffeur to tell the incriminating truth: that his car had been going 60 mph, not a pokey 30 or 40, when it zipped down Main Street so fast that it took two cops, a newsboy and a streetcar operator to decipher the license plate number as it zoomed by. “I told you to do it,” boomed Hancock, “and if the dinged machine can’t make it, I’ll buy another!”

On an August night in the same year, rowdies racing a big red car through downtown scattered pedestrians, and half a dozen policemen “tried in vain to stop it.” A few nights later, the same car drove up and down the streets of Angeleno Heights, laying on the horn and alarming the snoozing locals. The cop who gave chase this time followed the car down Temple Street to Spring Street and then south, where the “machine” again outran him.

In January 1906, San Francisco’s mayor, “Handsome Gene” Schmitz, was visiting. He was being shown around by a pro-labor City Council member named Arthur Houghton; the antiunion Times despised him, of course, and mocked him as “Spook Howton,” because he had supposedly conducted séances.

Anyway, the party was driving around in two cars when the chauffeurs — keep in mind that driving was a much trickier and more skilled business than it is now — asked their august passengers whether they could “let her out a bit” on the wide expanse of North Main Street. They did, and two motorcycle cops chased them for a good half a mile before they caught them. Once again, it was the chauffeurs who took the rap.

A “motorcycle fiend” was captured in May 1907 after he’d raced at a reported 70 mph through downtown streets — so fast that the pursuing cops had to dump their own motorcycles and commandeer a six-cylinder car that just happened to be passing. The car did catch up with the motorcyclist, who complained that even at 70 mph, his ride was “not in good order.”

This was a particular embarrassment because the LAPD had just a few months earlier bought motorcycles with a top speed of 50 mph, figuring nobody could go faster than that.

The Times had its own lexicon for these chases. Speeders were “scorchers” and women speeders were “fair scorchers.” Like Harriet Anderson, a recent Vassar grad who decided to speed along Mission Road into Pasadena in February 1908. Two motorcycle cops took out after her. One of her passengers, a gallant movie agent named John Reynolds, took advantage of the screen of dust being kicked up between car and cops to lift Anderson out of the driver’s seat and put himself behind the wheel, and stop the car.

When the cops walked up to the driver’s side, they were dumbfounded to see a man behind the wheel. “We thought a woman was driving this car,” said one. “Me too,” said the other. The chivalrous Reynolds followed them to police court and paid the fine that was by rights Anderson’s.

In October 1909, “fair motorist” Gladys Moore was stopped on South Flower Street. “Oh!” she said prettily to the cop, in the now-time-tested dodge. “Am I going too fast?” “You’re going just twice too fast,” gruffed the cop — 24 mph in a 12-mph zone. “I was just following the pace of the man in front of me,” Moore argued — another standard try. It will gladden your hearts to know that the man in front of her was also stopped and ticketed.

Los Angeles bills itself as the home of endlessly clement weather. But Southern California’s mix of microclimates isn’t immune to dramatic storms.

In time, the news novelty wore off, unless someone got hurt or killed.

And then, a certain ex-football player set the gold standard for televised police chases.

On a fine June afternoon in 1994, instead of turning himself in to the cops, as his lawyer had promised, double murder suspect O.J. Simpson hit the road, threatening to shoot himself in the back of a white Bronco that was being driven up and down two counties by a friend. It was a slow-speed chase, which maximized the airtime and the audience.

NBC was airing the NBA finals at the same time, and the network went back and forth — which story should occupy the big screen, and which one a small screen-within-screen? In the end, it put the NBA game in the corner and Simpson on the big screen.

Not long ago, a Houston news site relayed the story that the then-coach of the NBA’s New York Knicks, Pat Riley, had happened to meet Simpson’s friend Al Cowlings not long after the chase. As ABC sports analyst Jeff Van Gundy quoted Riley, Cowlings explained why he was driving the Bronco so slowly: “O.J. wanted to hear the end of the game on the radio before he pulled in.”

For the record:

5:53 p.m. Nov. 8, 2022A previous version of this article misidentified the team Pat Riley coached in the 1994 NBA Finals as the Houston Rockets. Riley coached the New York Knicks.

Until then, the most stunning televised chase had happened in January 1992, a 300-mile, four-hour pursuit from the San Joaquin Valley to Orange County, during which the driver killed a good Samaritan, stole his red VW Cabriolet, and was finally shot by cops as he took aim at them.

Three L.A. stations covered it from the air, and when Channel 13 tried to switch back to its regular programming, viewers howled. “In 22 years in the news business in Los Angeles,” the station’s respected news director, Jeff Wald, told The Times, “I’ve never had people call and say, ‘I want to see the chase.’”

The novelty and the visuals were so powerful that The Times wrote four stories about it: a main story with a map, a profile of the victim, a story on the gunman’s brother who got a call from his brother about 12 hours before the chase; and an analysis of the live TV news coverage.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Baldy? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

Incidents beget an appetite for more of them. A Reddit user asked four years ago for help finding a service to text him when a police chase is happening. “Since moving to L.A. I have fallen in love with this L.A. pastime … but always seem to miss them.” Twitter feeds like @lapolicepursuit are glad to oblige.

We’ve had several decades of live TV chases, and several decades of debate about them: When and how long to broadcast them? And when and how police should give chase? In 1999, for one example, law enforcement took off after a man whose car had expired registration tags. It ended many miles later, with the man shot to death after pointing a gun at cops. What’s the provocation versus the payoff?

Ratings and arrests are not the only numbers that matter here. In 2017, Times reporting revealed that LAPD chases injured bystanders at more than twice the rate of chases in the rest of the state. A grand jury report recommended better training for local officers and questioned whether nonviolent offenders needed to be pursued.

California’s law enforcement standards and training commission, POST, describes a “balance test” of guidelines and parameters, revised earlier this year, for deciding when to give chase.

Yet chases still end in tragedy for bystanders.

Also five years ago, the New Yorker’s “Obsessions” series took up L.A.’s appetite for watching police chases, and posted a documentary that reckoned that since 1979, more than 13,000 people nationwide have died in these high-speed chases, 90% of which began with nonviolent offenses.

No single, catastrophic incident will end police pursuits, or the debate about them. And no single, catastrophic incident will end live TV coverage of them.

But every once in a while, one of them makes you think that this will be the one to do it.

For me, that one came on a bright April afternoon in 1998.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

If you didn’t see it or read about it then, you’re better for it. Local stations apologized to viewers at the time: “We didn’t like them seeing what they saw any more than they did,” a spokeswoman for Channel 11 told The Times then. And broadcasters make a point to be more careful with live helicopter coverage today.

It wasn’t even a proper chase. A man stopped his gray truck on the soaring transition between the 110 Freeway and the 105, the best place for news helicopters to show what he was about to do.

He laid out a sign for the cameras and dropped a videotaped suicide note.

He pointed his shotgun at passing cars, and pretty soon, the cops were there, and the helicopters were there. Two stations cut away from children’s programming — and wound up broadcasting the tormented man’s suicide.

I still drive that freeway interchange every week, and every week I think of him, and of his dog, Gladdis, who died in a fire her owner set in the truck. And the seven helicopters overhead. And the untold number of us watching on live TV.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on Tuesdays on latimes.com.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.