A year’s worth of Northern California’s rainfall has gone missing since 2019

- Share via

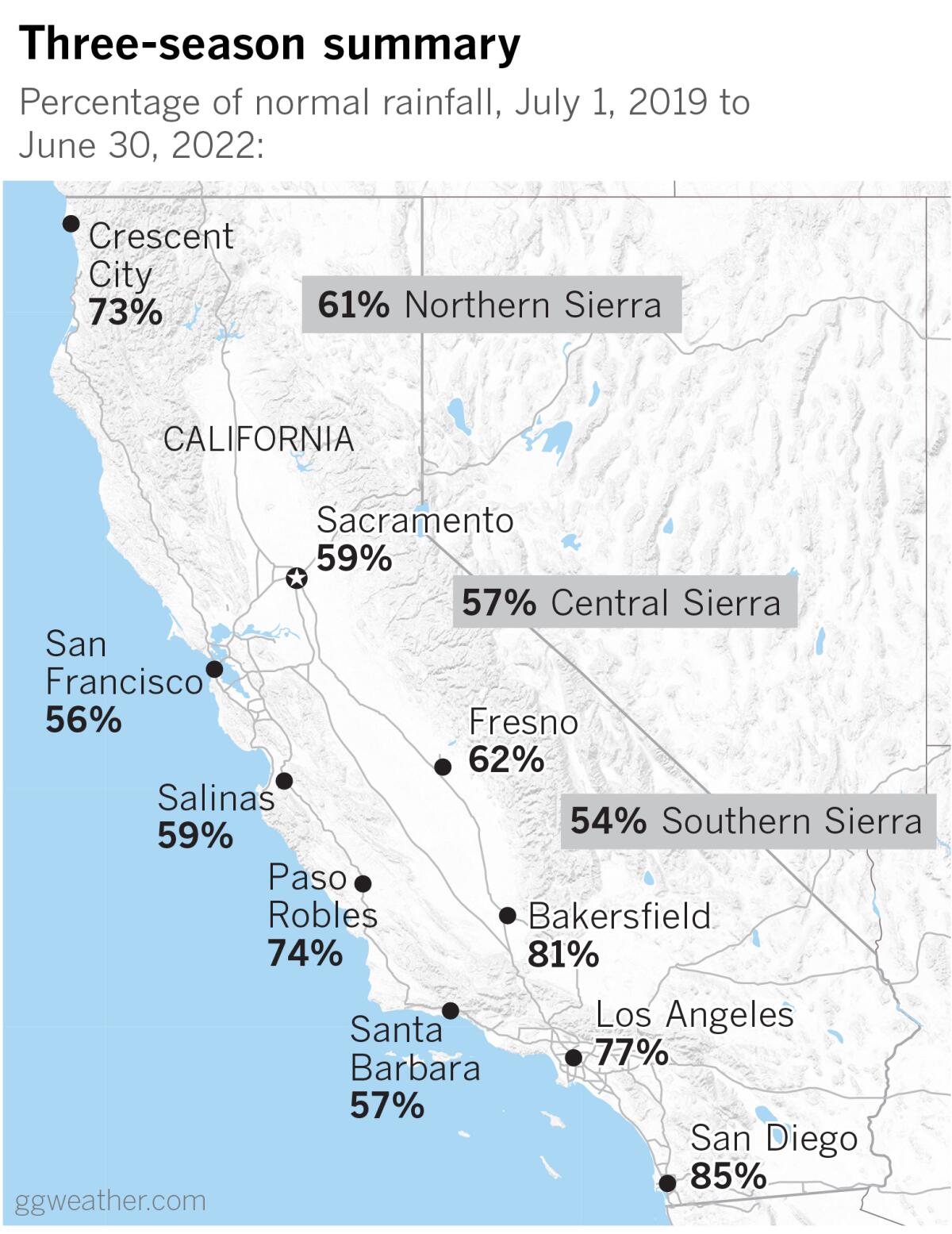

Much of Northern California received only two-thirds of its normal rainfall for the last three years, according to meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services.

“It’s like working for three years and only getting paid for two,” he said.

Some places, such as Ukiah, Santa Rosa and Mount Shasta City, did even worse, logging about half or less of their normal precipitation.

Null compiled a summary of the three rainfall seasons from July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2022, and the figures starkly illustrate the severity of the drought in the state.

Places in Southern California fared better, with downtown Los Angeles getting 77% of normal rainfall for the three-year period, and San Diego coming in at 85%. But precipitation in the northern part of the state is much more consequential for Southern California and the Golden State’s elaborate plumbing system than what falls south of the Tehachapi Mountains. Most of California’s significant precipitation occurs in the north. Rainwater and snowmelt are captured there in huge reservoirs such as Shasta Lake and Lake Oroville.

If he could pick a single number to characterize the state’s water situation, Null said, it would be the Northern Sierra 8-Station Index. What he called the “bellwether” stood at 61% of normal for 2019 through 2022, less than two-thirds of what would be expected.

The index is the average of eight precipitation-measuring sites that provide a representative sample of the northern Sierra’s major watersheds. These watersheds include the Sacramento, Feather, Yuba and American rivers, which provide a large portion of the state’s water supply.

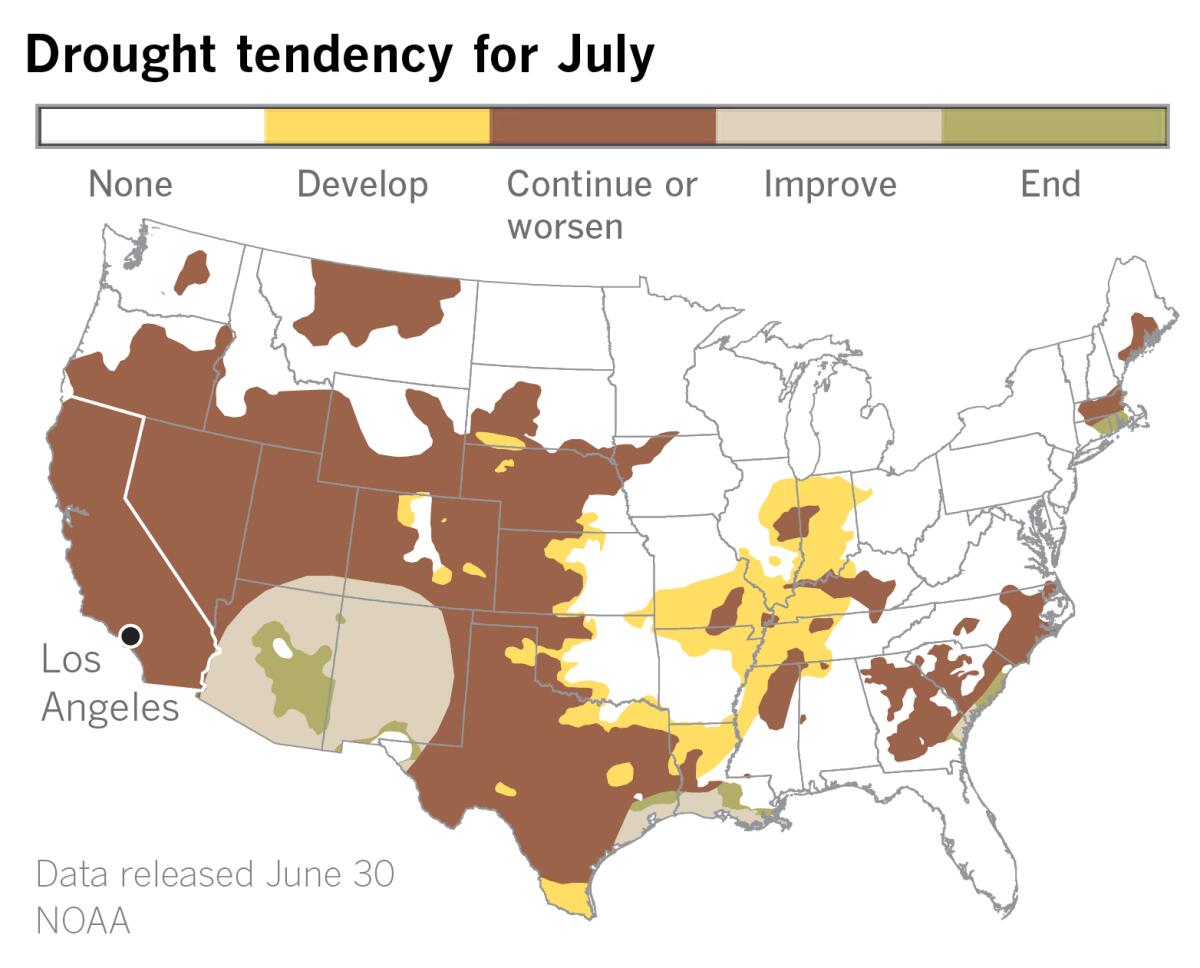

And that supply is tight. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, most of the state is in at least severe drought, and about half of the state is in extreme drought. Nearly 12% of California is considered to be in exceptional drought, the worst category. Because of the state’s Mediterranean climate of generally rain-free summer months, there’s no immediate prospect for relief. Moreover, a La Niña climate pattern in the tropical Pacific, which typically results in dry winters in Southern California and the Southwest, is expected to continue into a rare third year.

Rising temperatures and an ever drier climate due to climate change are amplifying drought in what is the driest 22-year period in the West in 1,200 years.

December was unusually wet and snowy in the state, but then the spigots were shut off for the next couple of months, which are usually the wettest. According to Null, a strong atmospheric river in December doused the state from about Monterey to just north of the Golden Gate, and from about Yosemite to Oroville. But even within that target area, precipitation numbers came up short. San Francisco, for example, ended the 2021-2022 rainfall season with 82% of normal, but for the three-season period ending June 30, it had only 56% of normal.

Places such as Ukiah and Mount Shasta City, for example, weren’t as lucky. They ended up with 43% and 45% of their three-year normals, respectively, because they were north of the December atmospheric river and too far south for storms that wet down the far northwestern corner of the state, according to Null. Santa Rosa ended up with only 55% of its three-year normal.

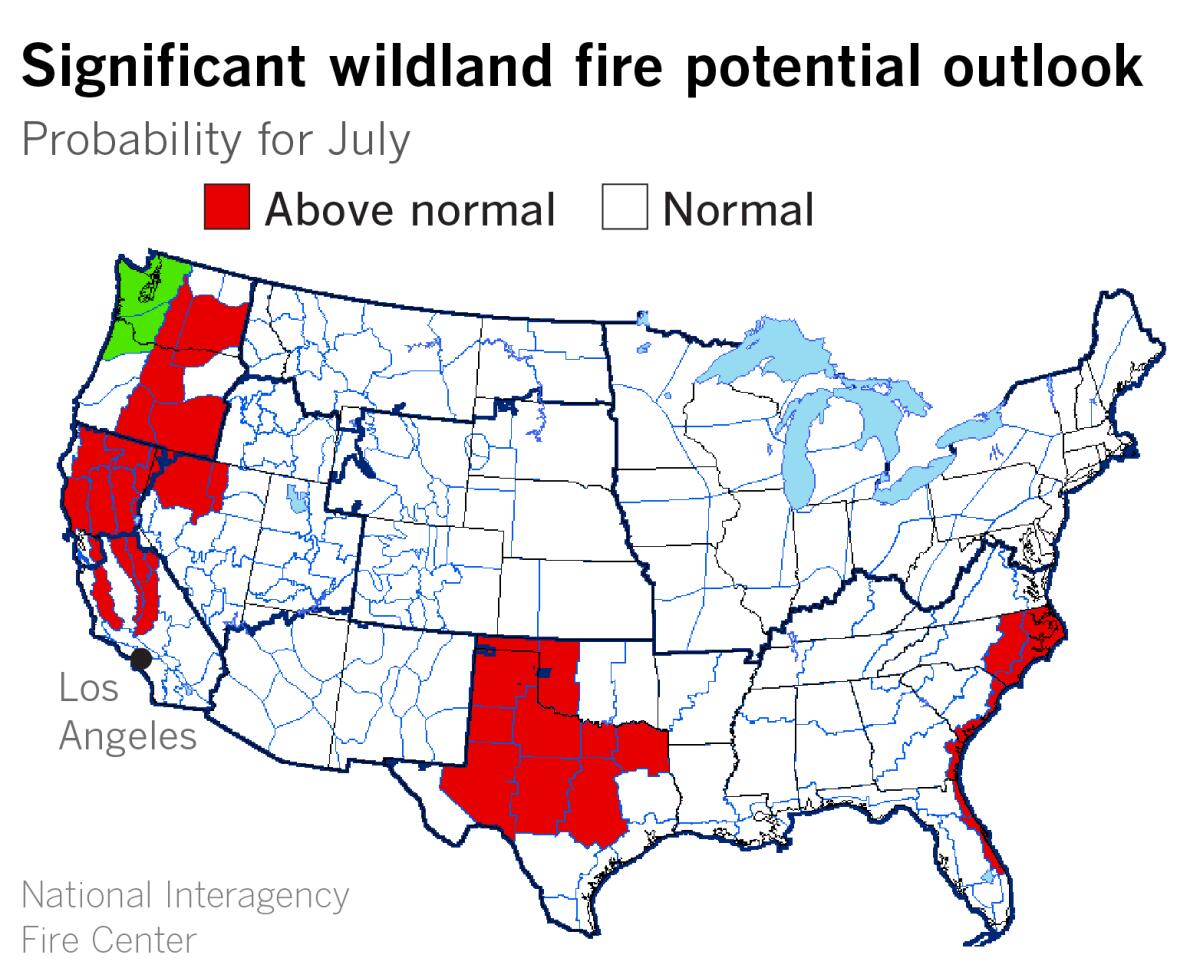

This missing year of rainfall contributes to the drought and a tinder-dry environment that is much more prone to wildfire. The National Interagency Fire Center’s outlook for July calls for above-normal potential for wildfire north of the Interstate 80 corridor. Above-normal potential wraps southward from there toward the Tehachapi Mountains through the coastal ranges and the central and southern Sierra Nevada.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.