Column: Vicente Fernández’s journey was our parents’ journey. Long may they live

- Share via

This fall has been a season of death for the people of my ancestral town of Jerez, Zacatecas.

The daughter of an Anaheim High classmate of mine passed away last month. A legendary East Los Angeles chorizero — a chorizo maker — lost his battle with cancer last week. The father of a dear family friend passed away just this Wednesday.

The deaths are weighing on my father, who now attends funerals and wakes the way he used to go to baptisms and quinceañeras. Jerezanos in Southern California easily number in the thousands, and Papi seems to know them all. He’s 70 now, in the autumn of his life, a once-virile man now grayer, skinnier, slower and calmer.

Ever since the death of my mother two years ago from ovarian cancer, Papi has become existential as he tries to get his affairs in order for the day he, too, will leave us. So when I called him this morning to let him know about the death of Mexican music and movie icon Vicente Fernández, I didn’t know what to expect.

Fernandez’s death wasn’t shocking. Millions of fans across the United States, Latin America and beyond have kept a vigil since August, when the man nicknamed Chente fell at his ranch in the Mexican state of Jalisco and injured his spine.

They blared his songs from speakers in homes and cars and at shops and restaurants. Mourners piled flowers and candles around his star at the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

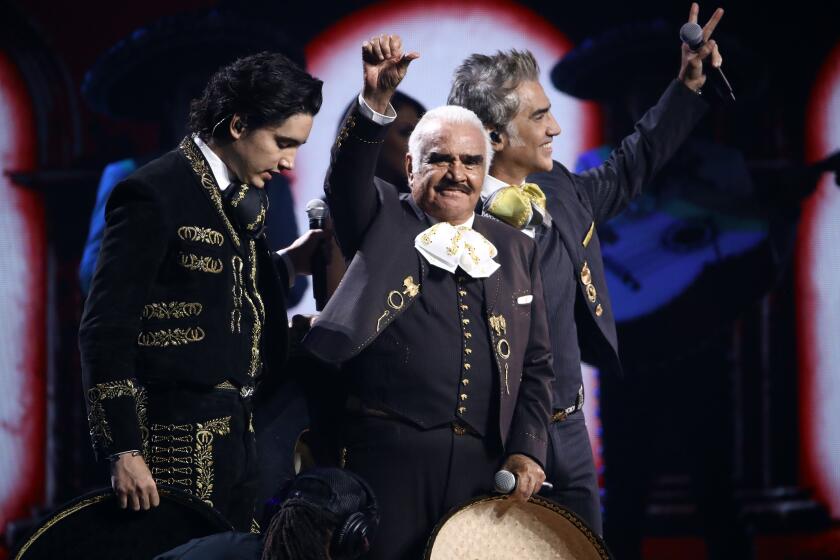

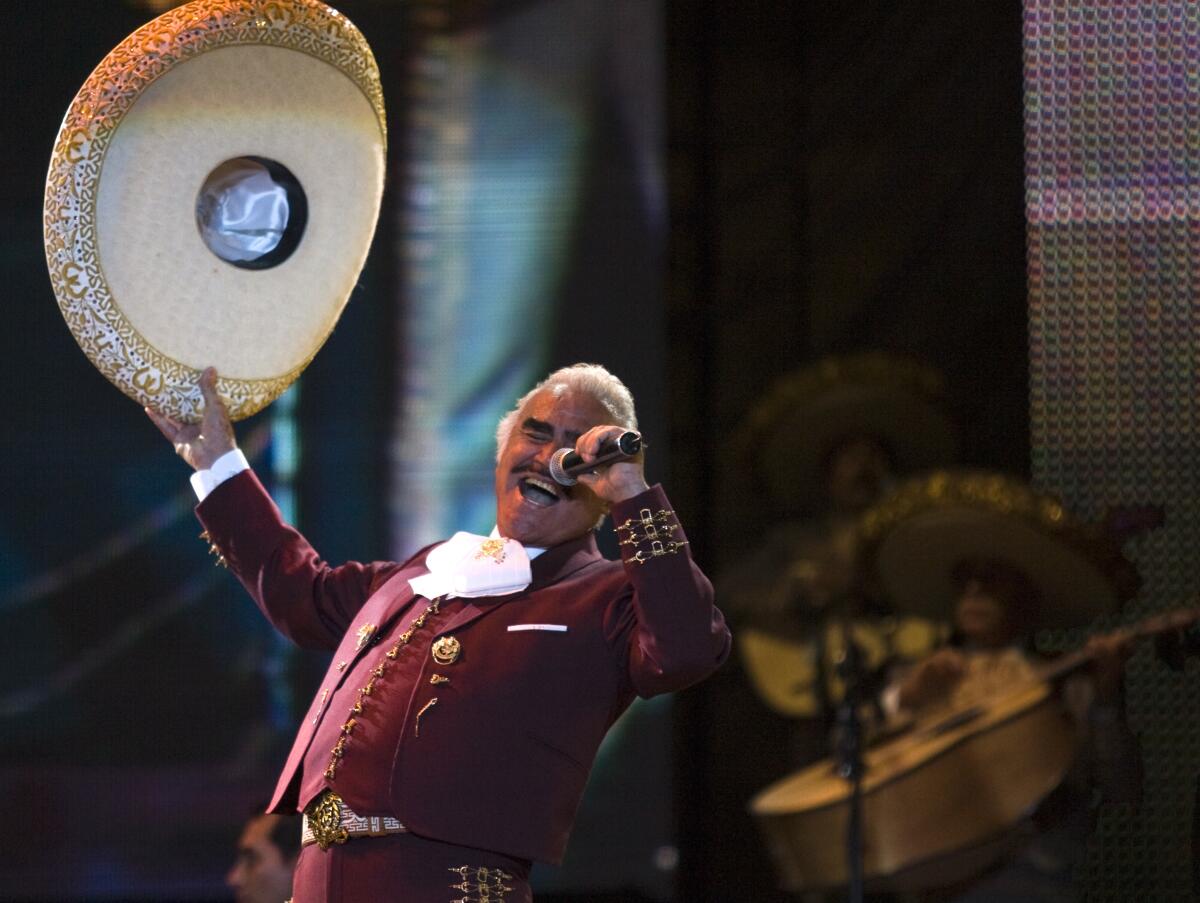

It’s the end of an era, for sure. Fernández bridged the gap between Mexico’s original matinee idols and today’s stars in a decades-long hit parade matched in American song only by Frank Sinatra. But that legacy wasn’t on my dad’s mind when I told him the news.

He was never the biggest fan — in our family, fellow zacatecano Antonio Aguilar was king. I can’t really recall the last time Dad played his music. Yet my dad was subdued when I broke the news.

“How sad,” Papi slowly said. He stayed silent for a bit. When he spoke again, his voice quivered. “Que en paz descanse,” Papi said. May he rest in peace.

Papi mourned for Fernández — and also for himself and his generation of Mexican immigrants in the United States.

They saw Chente not just as an avatar for mexicanidad, as a swaggering macho with a mighty mustache and voice that could knock down the walls of Jericho. That’s how my generation of Mexican Americans and those younger than me will remember Fernández.

Chente was more than caricature to our parents, especially our fathers and uncles — he was them every step of their life in the United States, where he ultimately became more popular than in Mexico.

A minute after we hung up, Papi called me again (he always does that). Now, his tone was happier. He was suddenly 18 years old, a self-described mojado — a wetback — who had just arrived in East Los Angeles in 1969 to join his brothers in a new country. The soundtrack in all the bars along Olympic and Whittier boulevards back then? Chente.

“They’d blast the volume on the radiola!” my dad said with glee, rattling off the names of long-gone cantinas he haunted — El Hernandez, La India Bonita, Flamingo Inn — and Chente’s big songs back then, “Tu Camino y El Mío” and “El Remedio.” Papi laughed at the memory, then said, “And we drunks would yell and throw back our cervezas and sing along.”

What particularly thrilled my dad and his friends was how Chente always shouted out his own village of Huentintán, Jalisco. In a time and place where Americans and even Mexican Americans shunned Mexican immigrants, my dad and his peers felt seen, and their way of life validated.

Chente’s triumphs became the triumphs of Dad and his generation as they found their own success. The singer went from performing at old movie palaces in downtown Los Angeles to arenas and stadiums across Southern California and beyond. My dad and his brothers went from sharing beds to buying their own suburban homes.

The star and his fans conquered el Norte by adhering to rancho libertarianism, a philosophy that celebrates bootstrap individualism in a way that makes Ayn Rand seem like a commune-dwelling hippie. His tunes documented the pain and pride he and his fans experienced through life. There were never any excuses offered for hardships — just pride in being able to beat them down.

Latinos became the largest minority in the United States as Chente and my dad’s generation became older. My generation went from hearing Chente as the forced soundtrack of our weekends — he remained on the radio even as we begged our parents to let us play Nirvana or 2Pac — to a nostalgia act. He, like our parents, moved on into the realm of myth, until no longer quite human but living relics.

What made Vicente Fernández so consistently spectacular across four decades? Start with these songs.

Their style of mexicanidad is now in its winter. Machismo, the moral code that defined Mexican manhood for centuries, is no longer winked at or accepted. Immigrants from Zacatecas and Jalisco no longer dominate the social and cultural life of Southern California — it’s now people from Sinaloa, Oaxaca, Mexico City. Chente’s music is now largely ceremonial, not contemporary.

And as those days end, the reexamination of them is in full effect. Right now on social media, critics are listing Chente’s errors — his performance at the 2000 Republican National Convention, homophobic and sexist comments over the decades. Fernández got in trouble as recently as this January, when a photo of him groping a female fan went viral online, a transgression for which the octogenarian apologized even as he tried to play it off as no big deal.

No one will miss those moments or the worldview that tolerated them. But those defects are also a reminder that the totality of someone’s life should supersede their mistakes. Chente’s life is a way to look at our parents as who they were and are — flawed people whose feats inspired us to try and match their heights instead of mimic their faults.

That’s why the soundtrack in Southern California this Sunday is Chente and will be so for the next couple of days. Already, I’ve heard my middle-class Chicano neighbors, the ones whose Spanish is worse than mine, blast his music. The same with the taqueria near my wife’s restaurant and the random cars that pass by.

I’m playing Chente as well — to honor his legacy but also the elders in my community we’ve lost in the past couple of weeks and will lose in the years to come. To mark the end of an era, and to think about what’s next for us.

I’ll blast Chente and think about my father — an imperfect man who nevertheless has accomplished great things and now waits for his day to come. The song I’m playing on repeat is “Paloma Errante” (“Wandering Dove”), a 1970 track that topped the charts just after my dad came to East L.A.

“I raise my prayers to heaven / So that it calm my suffering,” Chente crooned — almost wept. “Eternal God, don’t abandon me / Give me joy, and the future.”

Que descanse en paz, mi Chente.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.