Behind the story: A lifetime of listening to Pepe Aguilar and his family suddenly becomes personal

- Share via

After the Beatles and maybe Tupac, there’s probably no music act whose songs I’ve listened to more than the collective output of the Aguilar family from Zacatecas: Father Antonio, wife Flor Silvestre; sons Antonio Jr. and Pepe; and Pepe’s children, Leonardo and Ángela.

Even if I didn’t always care for their stuff.

Their rancheras, norteñas, cumbias, corridos and bandas have been inescapable in my life, and are embedded in my DNA. My mother and father, a good decade before they even met, listened to Antonio and Flor at the Million Dollar Theater in downtown Los Angeles when Mami y Papi were young adults who had just arrived in the United States from the north-central Mexican state of Zacatecas and needed a respite from their hard lives.

One of my earliest memories is Mami and Papi taking my baby sister and me to an Aguilar show in the early 1980s at the Anaheim Convention Center. They were young parents who wanted to teach their children about their heritage in a three-hour show that combined rodeo and music. All I can recall now is horses and dirt and a good time; my dad remembers Antonio telling a preteen Pepe — then going by Pepito —“Saluda, mijo” (“Greet everyone, son”) to the laughs and kind applause of the audience.

The Aguilar canciones were the soundtrack for family get-togethers, and blared on car trips from Anaheim to Montebello, where most of my dad’s side of the family lives. My first girlfriend constantly played Pepe’s 1992 hit “Recuérdame Bonito” (“Remember Me Fondly”) on her Walkman while we took the bus back home from Sycamore Junior High in Anaheim; three years later, Antonio’s album “15 Exitos Con Tambora” (15 Chart-Toppers with Bass Drum”) was the first-ever CD my father bought.

They were so ubiquitous that I eventually tuned them out.

Like most children of Mexican immigrants in the United States, I eventually questioned why my parents had such affinity to music that not only sounded antiquated, but that I felt didn’t match up to the work of bigger Mexican artists like Pedro Infante, Vicente Fernández, and Los Tigres del Norte.

It didn’t matter: I couldn’t escape Aguilar anything. My parents would even play Antonio’s movies — Mexican-style horse operas — on Channel 22, back when it was Galavisión.

Thankfully, like any good child of Mexican immigrants in the United States, I eventually wised up.

Aguilar playlist

I realized that my parents saw our family in la dinastía Aguilar. They identified with Antonio and Flor, people like them who left Mexico to work and make a better life for their children. They saw Pepe in my siblings and me: American-born niños who grew up on both sides of the border and who might’ve rejected their mexicanidad for a spell but eventually came to embrace it as a way to navigate el norte.

And in Leonardo and Ángela, they saw the children of my cousins — fully assimilated millennials who know that there is value in the ways of their elders.

Most important? The music was good.

Once all this clicked, I became a fan.

And as I learned more about the Aguilar history, the idea for my Column One this week struck me: They weren’t just Mexican American entertainment royalty, but perhaps Southern California’s ultimate music dynasty. Their saga speaks to the region we were, are, and are becoming, one played out over multiple venues across the Southland over the past 60 years.

(How L.A. are the Aguilars? Check out this 2014 clip of Pepe performing the brassy standard “Un Puño de Tierra” — “A Fistful of Dirt” — backed by USC’s Spirit of Troy marching band.)

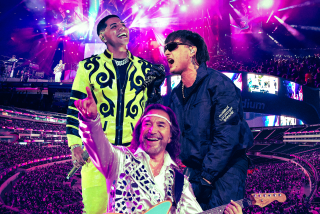

Aguilar and his family are Mexican American entertainment royalty — and a metaphor for modern-day Los Angeles, mixing English and Spanish, mariachi and Guns N’ Roses.

Writing my feature on Pepe y su familia was a personal and professional joy. But it also became poignant because of my late mom.

On Sept. 8, when “Jaripeo Sin Fronteras” — “Rodeo Without Borders,” Pepe’s update of his family’s revue — came to the Honda Center, my sister, brother, brother-in-law and father all attended. It was our first family night on the town since Mami passed away in April.

The “Jaripeo sin Fronteras” performance at the Honda Center in 2018 was the last concert she attended, and one of her final public outings. It didn’t matter that she was going through chemotherapy: Mami loved to hear Pepe’s music and wasn’t going to let fourth-stage cancer get in the way of a good time.

As we enjoyed Pepe and his clan this year, we remembered the time I called in some favors so that Mami could meet him backstage after a 2016 show at the tony Renee and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa. Dressed in heels, jewelry, a red shawl, and a sharp black purse, Mami proudly told Pepe that she remembered him performing as a child and was proud of what his family had accomplished on behalf of all zacatecanos. And she told Ángela that she was as beautiful and talented as her abuelita, Flor Silvestre.

My sisters say to this day they never saw Mami happier than when she introduced us kids to Pepe and his family — one American Dream meeting another.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.