Whistleblower or flamethrower? California Medical Board member calls out his colleagues

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — The pleas for help find him. They arrive by email or seep into his social media account. One showed up in a tightly sealed letter to his home. After years of feeling ignored by the Medical Board of California, the writers hope he’ll finally be the one who hears them.

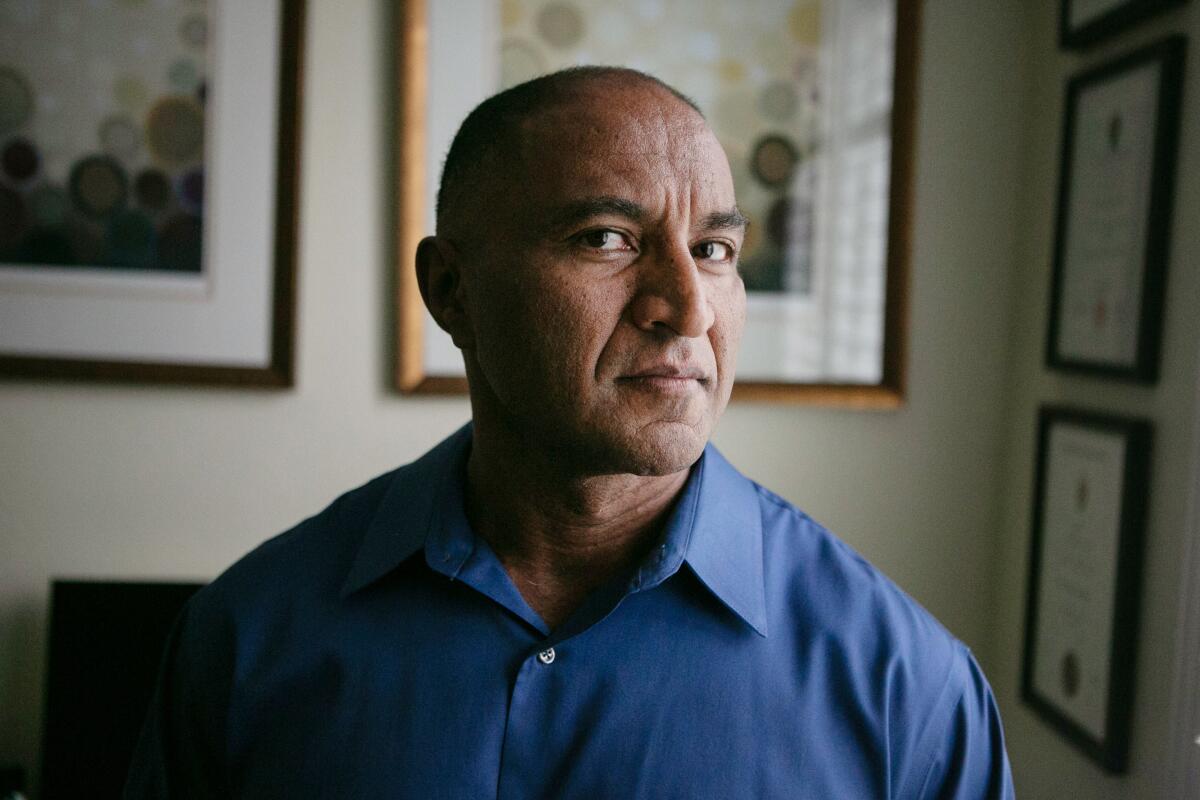

Eserick “TJ” Watkins can guess the types of allegations that could be waiting inside: the stories of a doctor’s misconduct that left an over-prescribed teen addicted, a father missing a limb, a daughter dead. He has heard hundreds of these cases as a member of the medical board, which oversees the discipline of doctors in the state.

Watkins used to forward the pleas to board staff, but now he finds it pointless. California’s medical board, Watkins said, is designed to silence aggrieved patients, a doctor-led panel that protects fellow doctors.

For decades, patient advocacy groups have accused the board — composed of eight physicians and five public members — of being too solicitous to the doctors it regulates. A few lawmakers over the years have taken up their cause, eking out watered-down reforms in the face of a powerful doctors’ lobby.

But now it’s an insider calling for change. In an extraordinary move, Watkins last week filed a whistleblower complaint with the state auditor’s office urging the agency to investigate the inner workings of the board and its decisions, which are largely cloaked under the law.

“It’s one thing to not feel heard; it’s another to be dismissed and ignored,” said Watkins, 48, one of the public members. “The main thing that people who write to me want is for this not to happen again. They have made peace that nothing will happen with their particular case, but they fight because they don’t want this to happen to anyone else. I feel that.”

Serious malpractice leading to the loss of limbs, paralysis and the deaths of patients wasn’t enough for the California Medical Board to stop these bad doctors from continuing to practice medicine.

Watkins said he’s been ostracized by most members for his unrelenting pushback against their decision-making. Board members have accused Watkins in open meetings of grandstanding and likened his approach to “throwing a grenade in the room.”

Board President Kristina Lawson said that Watkins’ concerns have been listened to at length and that the board is committed to protecting consumers and ensuring access to quality medical care.

“Board members and our staff work tirelessly in furtherance of this mission,” Lawson said in an interview.

Watkins said he expects tensions to get worse now that he’s upped the ante with the whistleblower complaint.

“If that legal veil gets lifted, you and everyone else will see what I know — and there will be outrage,” Watkins said.

::

The voice of one man changed Watkins, striking him so profoundly that even three decades later he can feel the weight of his words.

Watkins is of mixed race, and in apartheid South Africa his family had been forced out of their home in the Cape Town mountainside and into an impoverished township on the Cape Flats with other people of color.

The battle between would-be reformers and the California Medical Assn. gained fresh momentum this week in the wake of a Times investigation that found the Medical Board of California consistently allowed doctors accused of negligence to keep practicing.

It was a place that lacked hope. A place where people were stripped of their voices, where pleas went unheard. Watkins clung to education to avoid the fates of many boys his age — factory jobs or gangs.

Then, on Feb. 11, 1990, Nelson Mandela, who led the movement to end South Africa’s racist policies, was released after 27 years in prison. Then a high school senior, Watkins joined the hundreds of thousands who waited for hours to hear Mandela speak from the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall.

As day turned to night, Watkins felt an internal shift as he looked around at the sea of faces around him. Then Mandela spoke.

“That speech changed my life in ways that I can’t really articulate,” said Watkins, who later graduated from the University of South Africa, where he developed a love for competitive swimming and bodybuilding, before co-founding a medical imaging research company.

Watkins married an American and moved to the United States after being recruited for an executive training program in the Detroit automotive industry. His early vision of the country was based on posters he saw in grade school of the Golden Gate Bridge, Grand Canyon and other iconic landmarks.

“Nobody tells you that Detroit is not quite what you think of when you think of America,” he said with a laugh.

Los Angeles County officials are allowing the use of powerful psychiatric drugs on far more children in the juvenile delinquency and foster care systems than they had previously acknowledged, according to data obtained by The Times through a Public Records Act request.

Today, Watkins lives in the Sacramento area and works as a personal trainer and executive coach for politicians and chief executives in Sacramento. Among his clients is state Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), who appointed him to the physical therapy board in 2016 before naming him to the medical board in 2019.

Atkins said she was drawn to Watkins’ calm presence and high standards for himself and others when she hired him to be her trainer. With his help, Atkins said, she shed anxiety as well as weight.

“I had to be serious about it,” she said, “or he wouldn’t keep me as a client.”

Atkins said Watkins proved to be a good fit for the physical therapy board, rising to become vice president. When she needed to name someone to the medical board who wasn’t a physician, she asked him whether he would be up for a different challenge.

“He’s an incredible lifelong learner,” said Atkins, who declined to comment on Watkins’ critiques of the board. “I would be on the treadmill dying and he would talk to me about issues related to business practices, the books he reads — I can’t keep up.”

Watkins said he was just six months into his four-year term when he began questioning decisions during closed-door board sessions. He said his new colleagues told him he didn’t understand the issues yet, so he continued to wait, continued to listen.

A judge on Friday sentenced a Rowland Heights doctor to 30 years to life in prison for the murders of three of her patients who fatally overdosed, ending a landmark case that some medical experts say could reshape how doctors nationwide handle prescriptions.

But the voices he heard loudest were those of anguished patients and their families — the newly bereaved who wrote to the medical board for the first time and the regulars who relive their losses as they call in to public board meetings.

“People who go to this board are trying to have a voice,” said state Sen. Melissa Hurtado (D-Sanger), who has criticized the board’s lack of transparency and handling of complaints. “TJ is their voice. He is trying to make government better.”

In February, Watkins began pushing for answers in public meetings, grilling his colleagues and board staff on how often they handed out significantly lighter punishments than called for by the board’s guidelines. Patient advocates could hardly contain their shock.

“We were texting each other, ‘Oh my gosh, are you watching?’” said Marian Hollingsworth, co-founder of the Patient Safety League, who has fought the board since 2012 over two complaints she filed after her father’s death. “We had been banging our heads against the wall because it felt like our concerns fell on deaf ears.”

In March, Watkins openly condemned the board during a legislative oversight hearing at which lawmakers were considering changes to the body.

“The force of his statement was a surprise,” said Carmen Balber, executive director of Consumer Watchdog, which advocates for patients’ rights and is pushing a ballot measure to increase the maximum award allowed in medical negligence cases. “We’ve never heard something like that from a public member or not. Political appointees don’t typically rock the boat.”

Watkins said he was at the point of pulling out his closely cropped hair when he told lawmakers the board was putting patients at risk by allowing bad doctors to continue to practice. Lawmakers themselves lamented that they could not assess why the medical board was repeatedly allowing doctors accused of negligence to be placed on probation.

“The problem is when you ask questions, they say it’s physician confidentiality and we can’t discuss disciplinary cases,” Sen. Richard Roth (D-Riverside) said of the board this year.

A Times analysis showed the medical board received nearly 90,000 complaints against doctors in the last decade from patients, nurses, fellow physicians and others. Of those, board investigators substantiated 3,100; the disciplinary action that followed mostly consisted of probation or a letter of reprimand. The board revoked 439 licenses — fewer than 0.5% of the original complaints.

“Obviously they are not protecting the public, but absolutely protecting doctors,” Watkins said.

Efforts this year in the Legislature to change the enforcement process of the medical board hit a familiar brick wall: the influential California Medical Assn., which lobbies for doctors.

Still, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill into law last month that implemented a handful of long-sought reforms to help the financially struggling board, including the ability to seek reimbursement from disciplined doctors for investigations and raising physicians’ licensing fees. The California Medical Assn. claimed victory in ensuring those fees were capped at a level lower than what was initially proposed.

Under SB 806, the director of the Department of Consumer Affairs will appoint an enforcement monitor to oversee the medical board’s disciplinary actions and handling of complaints by March 1, 2022.

The doctor lobby’s biggest win, critics say, is in batting back attempts to change the makeup of the board so that public members hold a majority of seats.

::

Watkins’ words tumbled out in a quick succession of medical jargon and board acronyms from inside his Sacramento-area living room, but his speech slowed when he sensed the line. He has to balance what he wants to say with what he is permitted to divulge. He said he believes some medical board members are waiting for him to cross into censurable ground, such as by disclosing privileged information from a closed-session meeting.

He declined to speak about specific cases, instead dispensing criticisms in generalities. He also steered clear of politics, which critics contend envelop the board.

“I’m not dependent on the political space to make a living,” said Watkins, who earns a $100-per-diem rate as a board member, which amounted to $13,000 last year, according to state payroll data.

But the political implications of speaking out are there, set against the backdrop of the contentious ballot measure, likely to appear on next year’s ballot, to overhaul the state’s 46-year-old law capping damages in medical malpractice lawsuits at $250,000. The fight will pit doctors and their lobbying arm against trial lawyers and some of the board’s regular critics.

Watkins said he is focused on the board’s work, not the ballot measure, even if he considers some supporters of the initiative friends. He said he has declined meeting requests with proponents of the ballot measure. It’s the board’s flawed decision-making process, he said, that he wants to fix.

To some critics, his outspokenness is the problem.

“In my eight years on this board, I have not encountered another board member who has been so negative about our process as Mr. Watkins,” board member Dr. Howard Krauss, a Santa Monica neuro-ophthalmologist, said during an August meeting.

Krauss, apparently exasperated, acknowledged flaws and problems that he said were outside the board’s control, but added that members were working with the Legislature to make the board more effective.

“It worries me that this unrelenting criticism is going to become destructive of our leading to a positive outcome for this board,” Krauss said before encouraging other board members to reach out to Watkins to “bring TJ around to working productively and appreciating our staff and our board processes rather than throwing a grenade in the room.”

(Krauss later declined an interview request, saying board policy required him to send inquiries to its spokesman.)

During the August virtual meeting, Watkins kept his tone measured, lacing his fingers while he listened. He responded that he knew where the issues lie with the board and that the statistics he compiled prove it is “very lenient toward doctors.”

He said the board routinely accepts the opinions of medical experts paid by accused doctors over its own experts, which has significant implications for disciplinary cases.

In her interview, Lawson, the medical board’s president, denied the allegation. Lawson also said that, contrary to criticisms by advocacy groups and Watkins that patients are rendered voiceless, those complaining about doctors have ample say in the process.

“We’re always open and looking for new opportunities to make sure their voices are heard,” Lawson said.

Watkins argues that by the time the board votes on how to punish a doctor, legal memos produced by the attorney general’s office sanitize the details of the incident. For example, board members reviewing allegations that a doctor repeatedly made sexually inappropriate comments to patients are often not permitted to know what the doctor is alleged to have said, Watkins said.

Again, Lawson countered Watkins’ complaint. “I don’t believe those memos display any bias or ever attempt to downplay the seriousness of the case,” said Lawson, a non-physician member of the board since 2015.

Watkins said the board is able to avoid scrutiny because many investigative documents are deemed confidential.

“That’s where the bodies are buried, literally,” Watkins said.

He also alleged that the seriousness of cases has been downplayed in meetings. “It’s all, ‘Well, you know, it’s only one kid who died.’ I’ve heard that in a [closed-session] board meeting,” Watkins said.

“I’ve never heard a remark like that,” Lawson countered.

Lawson said Watkins had “recently refused to meet with us to discuss any individual cases of concern.” Watkins acknowledged turning down one request this year, saying he believed it was an effort to “build a better defense to try to discredit me.”

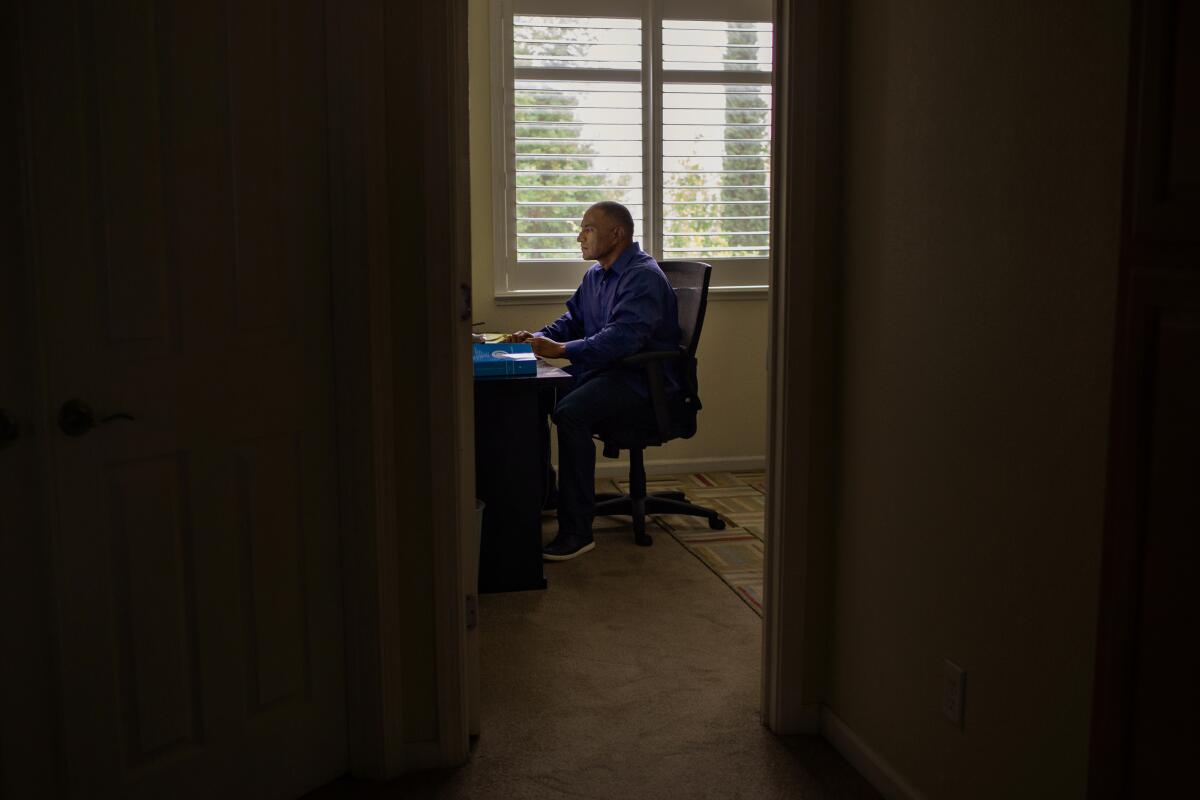

On Wednesday, the medical board will meet and, as he has for more than two years, Watkins prepared by poring over the confidential documents of disciplinary cases, looking for an argument that may persuade enough board members to reject settlements that he says minimize grievous misconduct or mistakes made by doctors. Too often, he said, the board is nothing but a rubber stamp.

“I told them that,” he said. “They tell me I don’t understand my role.”

However defined, that role does not end anytime soon. There is another year and a half of Watkins’ term on the board.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.