Why L.A. County has a politician with a gun and a badge: From Sheriff Villanueva back to 1850

- Share via

The sheriff is fit to be tied. Ditto the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, some of whom had supported the other guy for sheriff — the guy who lost. It’s a regular boardroom donnybrook. The supes bring charges and accusations. The sheriff defies and denies.

Sound familiar? It was 90 years ago, and that sheriff, John C. Cline, eventually got booted from his job — not by the supervisors, who didn’t have that direct power, but by a judge who agreed that Cline was guilty of public malfeasance.

We’re watching the newest chapter in the long, long L.A. story of sheriffs in uniform who have relished the optics of arguing across a hearing table with five civilian supervisors who can control the Sheriff’s Department budget but not how the elected sheriff does his job.

Now some deja vu from 1921 to the present: L.A. County’s current sheriff, Alex Villanueva, elected in 2018 over a one-term incumbent, faced a contempt hearing, for blowing off a subpoena from the civilian watchdog board. He’s been sued and sued again for keeping back records of deputy misconduct. His department has, in the words of one oversight commission member, a pattern of opening “criminal investigations” into “public officials and other professionals who are in conflict with the department.”

A judge told Villanueva he had overstepped his power in rehiring a deputy (and campaign volunteer) who’d been fired after trying to break into an ex’s apartment. (There’s video. ) Members of the oversight commission and two supervisors have asked Villanueva to resign.

Enough drama for you?

California’s Constitution makes each county sheriff an independent, elected official — a politician with a gun and a badge.

I know it didn’t happen like that in “Blazing Saddles,” when the dim-bulb governor was hornswoggled into naming Cleavon Little as the new sheriff, an actor who looked more sheriff-like than anyone since Randolph Scott.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

But once the L.A. County sheriff’s job description morphed into something that had less to do with hunting rustlers and more to do with rustling up money and support, the sheriff’s gun became incidental to his fountain pen. For example: Four-term sheriff Lee Baca, now in a federal slammer for obstructing an FBI investigation into jail abuse, got both a master’s and a doctorate in public administration from USC.

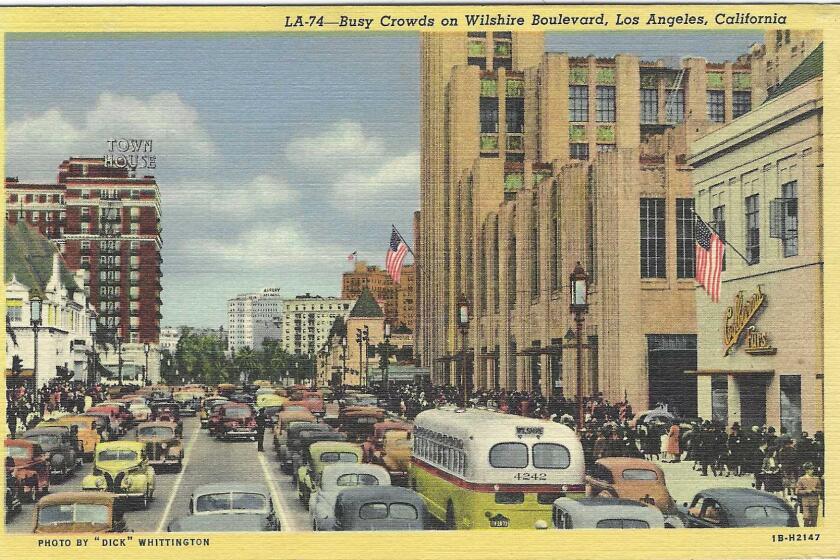

Today, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, which began in April 1850 with a sheriff and two deputies, fields more than 10,000 deputies, runs the nation’s biggest jail system, and patrols about 2,500 of the county’s 4,000-plus square miles, among other tasks.

What is the Sheriff’s Department’s turf? It doesn’t patrol the cities, like Los Angeles and Pasadena and Long Beach and Inglewood, which have their own police departments. But it is the de facto police force for unincorporated parts of L.A. County, for desert, mountains and neighborhoods as far-flung as Marina del Rey, Willowbrook and Newhall.

And it is the actual police force for 40-plus contract cities in the county. A contract city is a city like West Hollywood or Compton or Lakewood; it may have its own city hall and libraries and parks, but not always its own PD.

Because a police force is just about the weightiest part of a city’s budget, contract cities can save themselves money by contracting with the Sheriff’s Department to do that work. Economy of scale, that’s the theory.

Combined, those contract cities pay over $300 million a year to the Sheriff’s Department for that arrangement, one-tenth of the department’s budget. (Some of those cities are now worried that they’ll somehow be on the hook for any lawsuits this disputatious sheriff winds up costing. Maybe they remember that very expensive fracas from 1989, after which the county had to pay almost $24 million to people who were wrongly arrested and even beaten by deputies in riot gear who waded into the bridal shower at the home of a Samoan American family in the contract city of Cerritos.)

The word “sheriff” still summons to mind the untamed frontier and a lone, mythic man with a badge its only civilizing force.

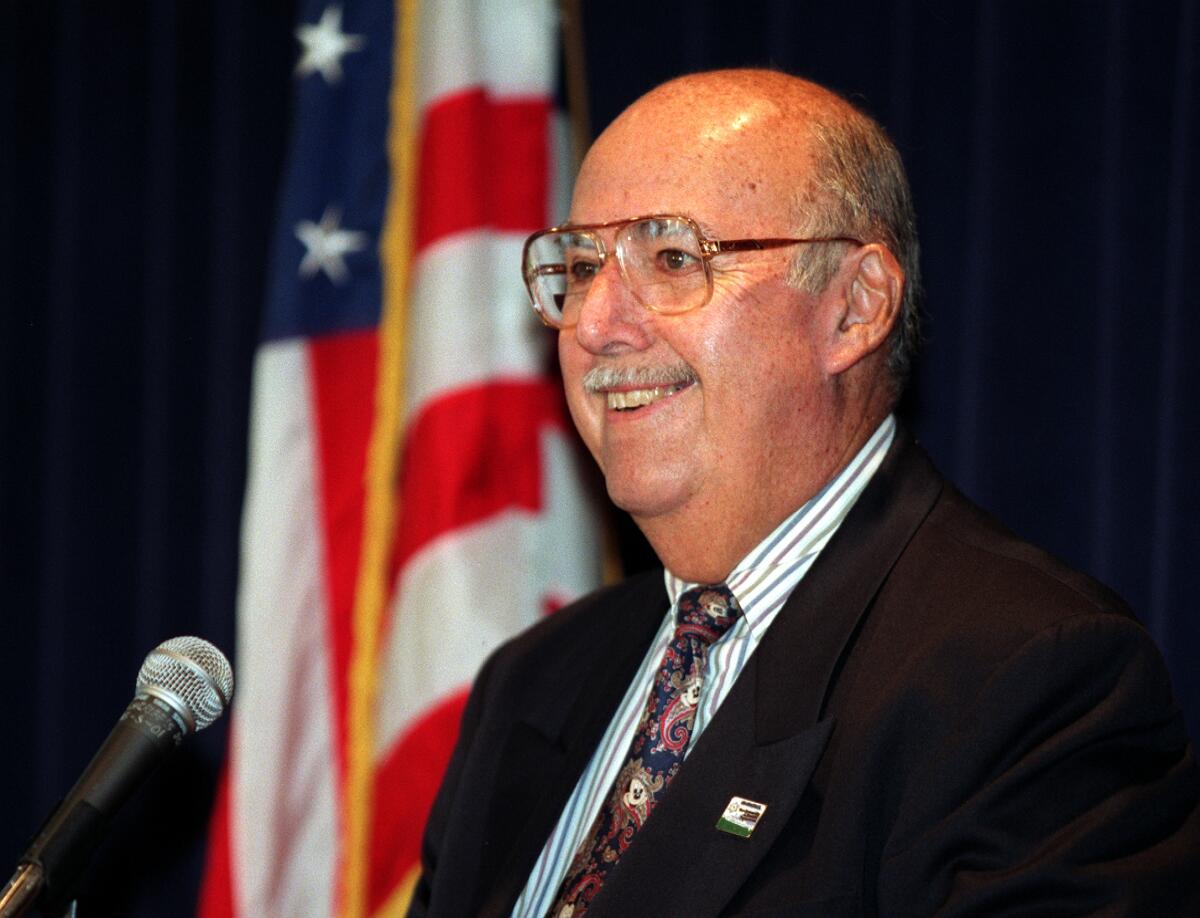

In 1998, Baca was sworn in after the first of his four elections as sheriff. He welcomed at the ceremony his predecessor-but-one, Peter Pitchess, elected six times, and who, upon his retirement, was sentimentally designated by the Board of Supervisors as “sheriff emeritus for the rest of his life.”

From that Olympian title, and from his wheelchair, Pitchess exhorted Baca with a message of virtual omnipotence: “You were elected sheriff. You are the sheriff. You and your colleagues will run this department [without] interference from outside.”

That kind of thing could go to a fellow’s head.

The L.A. County sheriff’s job predates the L.A. city police chief’s by a generation, which is one reason why the sheriff, as the county’s senior law enforcement official, wears five stars on his collar; and the LAPD chief wears four. (The sheriff has worn five stars at least since Baca’s tenure. I don’t know when the practice began, but if anyone has photos of his predecessors in penta-starred uniform, send ‘em along. The United States’ last five-star general, Omar Bradley, died in 1981.)

But in the last 60 years or so, the LAPD has eclipsed in fame — and sometimes in notoriety — its senior department.

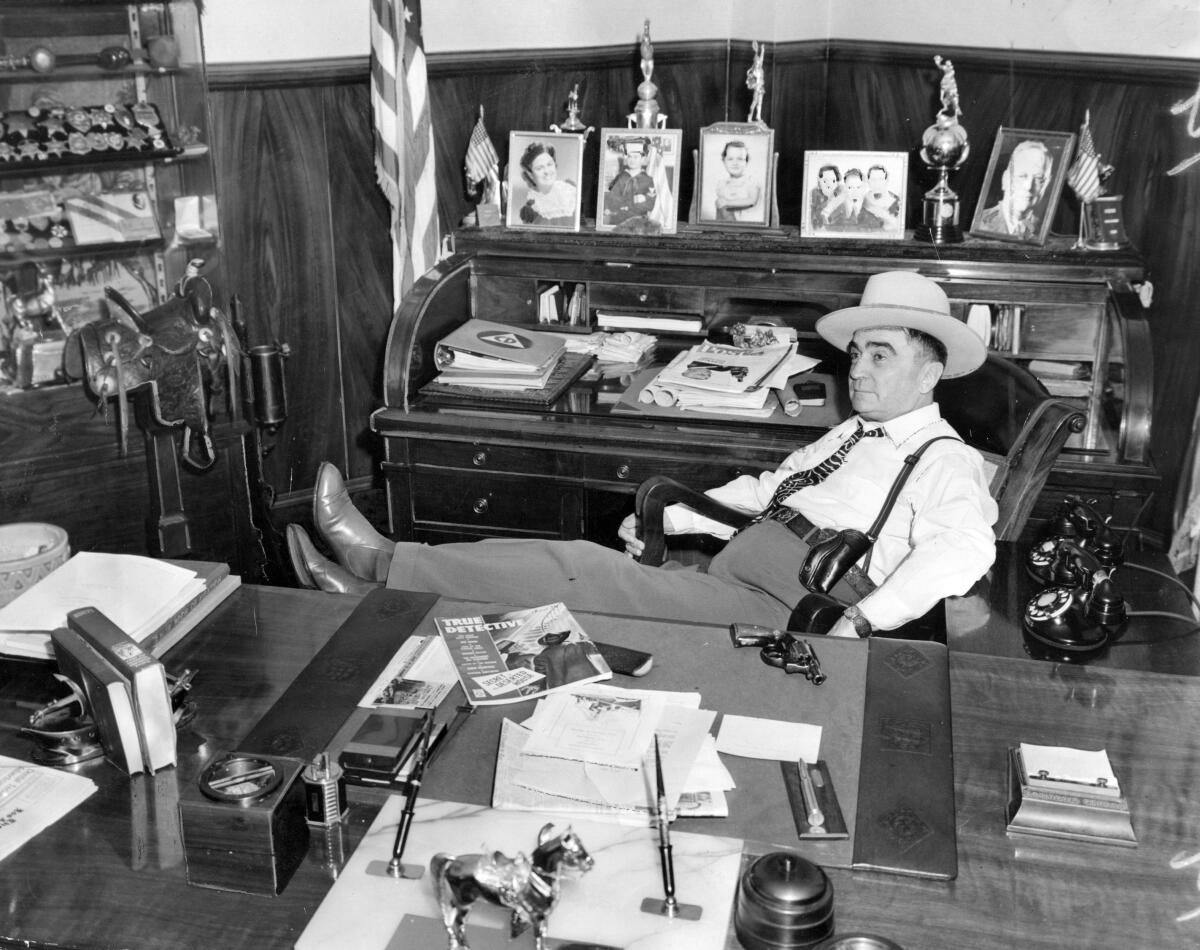

For years the L.A. County sheriff got a bigger paycheck than his better-known fellow politician, the president of the United States. Everyone could recognize the president, and some number of Angelenos could identify the LAPD chief, but really, to put it in cop terms: Except for the Central Casting sheriff Eugene Biscailuz, who won six terms unopposed, how many could pick an out-of-uniform sheriff out of a lineup?

The LAPD chief was once chosen through the civil service and is now appointed by the mayor, seconded by the City Council and police commission. The chief is limited to two five-year terms. In 2002, Angelenos voted big-big to put term limits on the elected sheriff, but Baca appealed, and that vote was tossed out as un-California-constitutional.

Until Baca resigned in 2014, the sheriff’s succession tenure was so pro forma that it made the House of Windsor look chaotic. Sheriffs served pretty much as long as they pleased, sometimes retiring just before their terms expired to give their preferred successor an inside track as an “incumbent” come election time, often with the wink-and-nod support of the board of supervisors. The result: In the 99 years from 1915, we had only six sheriffs.

One sheriff resigned to run for Congress. Another, Baca’s predecessor, Sherman Block, died a few days before the election, and still his supporters campaigned on the implication that Block dead was a better sheriff (and a better opportunity for appointing one) than Baca alive. In 1974, a candidate trying to unseat the anointed sheriff, Peter Pitchess, likened it to “attacking Zeus on a mountaintop.”

For some decades now, the LAPD has had Hollywood at its back. “Dragnet” actor and creator Jack Webb and Police Chief William Parker begat generations of LAPD cop shows.

Maybe it had to do with the uniform too. The LAPD’s ink-blue is as dressy and photogenic as a business suit. It originated as Union Army surplus fabric after the Civil War, and 19th-century officers wore it betimes with a cowboy hat, or with an Abe Lincoln stovepipe topper.

The sheriff’s uniform shirt is a frontiersman-khaki color. There was no real standardized sheriff’s uniform until 1933, when the department adopted a green shirt and trousers, bow tie and a cap. It looked so much like what the Texaco gas pump jockeys wore that the deputies complained fiercely. As retired deputy Chris Miller wrote in an online history of the uniform, the green shirt was finally abandoned in 1955 for the present khaki. (The first L.A. County sheriff, George Burrill, elected in 1850, swaggered over his beat carrying an infantry sword, which certainly would have given raggedy L.A. some tone.)

Angelenos can be spotted a mile away in other locales, waiting for the walk sign while locals jaywalk with abandon. What’s that about? And what happens when people do jaywalk here?

Paradoxically, L.A.’s appointed city police chief usually gets more time under the public microscope, and at higher magnification, than the elected sheriff does.

Raphael J. Sonenshein is executive director of Cal State L.A.’s Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs and knows this stuff forwards and backwards. Oversight is “a huge challenge for police departments,” he thinks, yet “the chiefs don’t have a privileged spot in the state constitution” the way sheriffs do.

“For generations, the police reform movement has aimed to improve the accountability of local police departments and their appointed chiefs. It’s been a lot harder to do that with elected county sheriffs.”

Sheriffs predate the police chief system and have been “surprisingly resilient and at times resistant in decades characterized by strong movements for civilian oversight of local law enforcement,” Sonenshein told me.

“County government just doesn’t have the same tradition of governance reform seen in city government. Elected sheriffs can be more popular than the county board of supervisors, and oversight mechanisms like policing commissions and/or inspector generals and/or citizen oversight commissions are only now coming onto the scene in significant numbers.”

But bodies in motion — even bodies like oversight commissions — tend to stay in motion, and the likelihood is that the public will welcome more sheriff’s reforms, not fewer. One obscure wildcard Sonenshein noted: “The state constitution gives the California attorney general the power to direct all sheriffs — a power they have rarely used.”

You can determine L.A.’s seasons by our plant life. For example, right now, it’s jacaranda-blooms-stuck-to-your-windshield season. And to understand the Southern California landscape you see, you have to realize that, like you, it is probably not from around here.

Wouldn’t that be something to behold? But even that couldn’t match something that never came to pass.

In 1967, the Board of Supervisors ordered a study into the “senseless and costly duplication and overlapping of services” between the Sheriff’s Department and the LAPD. Maybe the two departments should merge?

The sheriff liked the idea. The supes liked the idea. The L.A. mayor, Sam Yorty, liked the idea, and he swore that the recently departed and venerated LAPD chief Parker did too, essentially channeling Parker’s absentee vote from some blue heaven.

Then came the hitch in the two getting hitched: Which one would be in charge — sheriff or chief? Each, as it turned out, expected the other to knuckle under.

So it never happened, but what a monumental slugfest it would have been: blue vs. tan, Hamilton vs. Burr, Hatfields vs. McCoys, Godzilla vs. King Kong.

Yorty soon thereafter blew town for a trip to Europe, but before he did, he was asked whether he expected any opposition to a merger. And “Travelin’ Sam,” in uncharacteristic understatement, admitted, “Some.”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.