The Hollywood ‘Mafia princess’ was Robert Durst’s best friend. Did loyalty lead to murder?

- Share via

Their fateful friendship began more than half a century ago with a chance glimpse at a campus pool party.

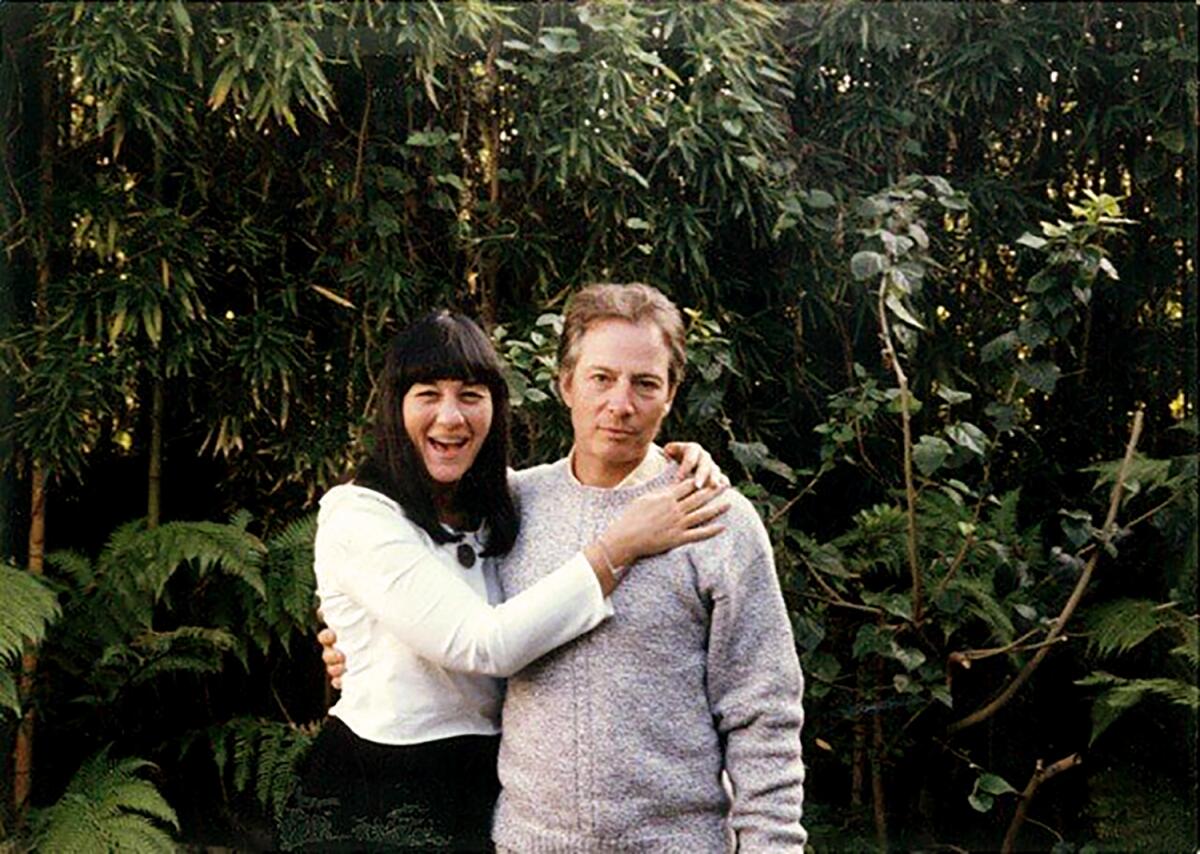

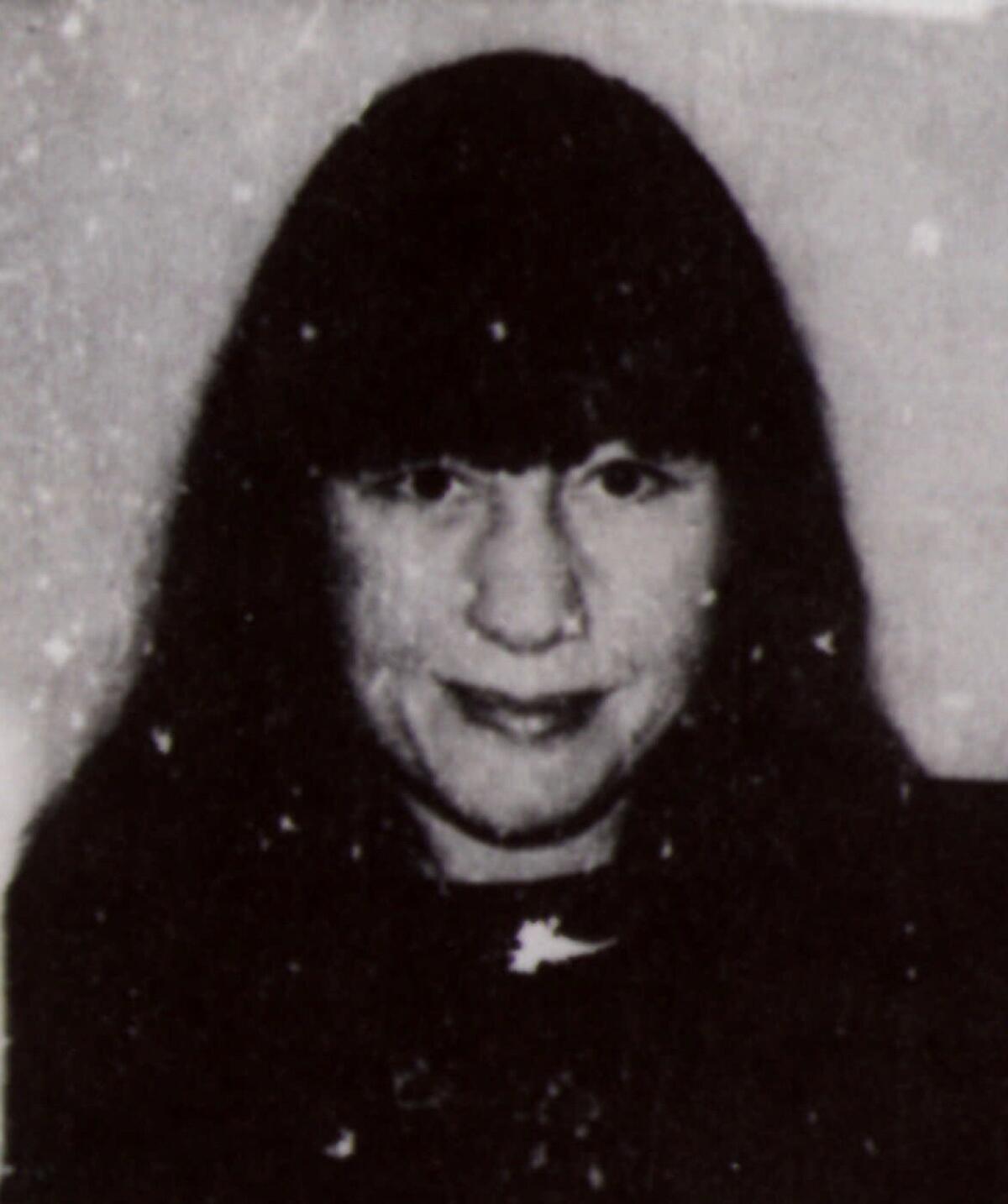

It was the late 1960s at UCLA, and Robert Durst — the eccentric heir of a New York real estate fortune — spotted a student with jet-black hair. Very pretty, he thought, as he walked up to introduce himself to Susan Berman, the spirited daughter of a Las Vegas mob boss.

Bobby and Susie, as they called each other, became fast friends — soon best friends. When Durst’s wife, Kathleen McCormack Durst, mysteriously vanished in 1982, Berman, a crime writer, served as his spokeswoman, shielding him from the media. And when Berman got married two years later, Durst walked her down the aisle.

“We stayed friends until she died in 2000,” Durst said, after recounting their first meeting during a 2010 interview with the director of “The Jinx,” an HBO documentary series about his life.

Now — two decades after Berman, 55, was found slumped in a pool of dried blood inside her Benedict Canyon home — Durst is on trial for her murder, in a slaying prosecutors contend was a desperate move to silence her.

The multimillionaire, 78, whose trial has resumed after a yearlong interruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, vehemently denies killing his close friend, and his defense team has long argued that the prosecution resulted from television hype surrounding “The Jinx,” not from evidence.

Jurors began hearing opening statements in Durst’s trial on March 4, 2020, the day California confirmed one of the first deaths from COVID-19. As the severity of the health crisis crystalized, the legal proceeding — then only a handful of days into a process expected to take five months — was paused.

Defense attorneys argue that the “unprecedented delay” has made it impossible for their client to receive a fair trial, and while the judge denied their request for a mistrial, both sides were allowed to deliver a new round of opening statements that began Tuesday, with prosecutors arguing that Berman knew her killer and let him into her home because she trusted him.

***

Friends have described Berman as the type of person to show up at your doorstep in a kimono asking to use the bathtub, or to drop off Jell-O and roasted chicken when you were sick. A mile-a-minute talker, she was, at once, manipulative and prone to phobia — of bridges, of elevators, of eggs — but also brilliant, big-hearted and, above all, loyal.

“Generous to a fault,” Berman’s friend Nick Chavin said during a pretrial court hearing in 2017, when he delivered damning testimony against another longtime friend, Durst.

Chavin testified that Durst once told him, following a dinner: “I had to, it was her or me. I had no choice.” He took the remark to be a confession about Berman’s death, he testified.

According to the prosecution’s theory of the case, Durst killed his wife years ago and enlisted Berman’s help with an alibi, asking her to pose as Kathleen in a phone call to her medical school dean that made it appear she was still alive.

Years later, prosecutors contend, Durst killed Berman to keep his secret safe after hearing rumblings that New York authorities were reopening an investigation into his wife’s disappearance.

Police received a cryptic letter postmarked the day before her body was found.

Inside the envelope addressed to “BEVERLEY HILLS POLICE” — a misspelling for Beverly Hills that Durst was known to use — was an anonymous note with Berman’s address and the word “CADAVER.”

For years, Durst publicly denied writing the note, but his defense team made a bombshell reversal in 2019, saying in court papers that they’d made the “strategic decision” to acknowledge he’d written the note. Durst’s lawyers said the acknowledgment didn’t “change the fact that Bob Durst did not kill Susan Berman and doesn’t know who did.”

“It has bothered me and haunted me virtually every day for 20 years,” Berman’s friend Christianne Clark said of her death.

In an interview, Clark, 76, said she had suspected Durst in the slaying since the early 2000s, when she learned that he had publicly admitted to dismembering Morris Black, a neighbor in Galveston, Texas. Durst had decamped to the Gulf Coast town and was living disguised as a mute woman after learning about the reopened New York investigation.

Durst claimed that Black threatened him during an argument and that a gun went off while Durst was defending himself. He cut up the body after drinking a fifth of Jack Daniels, Durst testified, saying he had decided not to go to the police because he didn’t think they would believe him. He was acquitted of murder.

Clark met Berman in the 1980s, while working for a nutritionist who coordinated healthy-meal deliveries for people across Los Angeles. Berman, a client who soon became a friend, often welcomed her in for coffee and mesmerized her with stories of her childhood.

“A Mafia princess,” Clark recalled, “that’s how she described herself.”

Susan Jane Berman was born in Minneapolis in the spring of 1945 but moved to Las Vegas when she was only 2 months old. Her mother, Gladys, a glamorous tap dancer, bundled up her new baby and took the train west, joining her mobster husband, David “Davie” Berman. Along with Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello, Davie helped run the mob’s gambling operations in Sin City, according to Berman’s memoir “Easy Street: The True Story of a Mob Family.” (On the acknowledgments page of “Easy Street,” Berman thanks only a handful of “special supportive friends,” among them, “Bobby Durst.”)

Berman grew up at the Flamingo Hotel, which her father helped run after its owner, infamous gangster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, was murdered. A painting of her in braids hung in the lobby. When she got bored, she would run to the front desk, ask for a key to an empty room, and order tomato soup and chocolate ice cream from room service. Aside from occasional kidnapping drills, she was largely ignorant of the dangers of her father’s world.

“He seemed the most normal of fathers to me,” she wrote. He doted on her, reading nightly bedtime stories and inviting Elvis and Liberace to sing at her birthday parties. But he also had exacting standards, once challenging her to memorize the (then) 48 states. The next morning, when she rattled them all off, her father sat silently, then asked, “What about the state capitals?”

Her sense of stability shattered at age 12, Berman wrote in her book, when her father died during colorectal surgery, and then, again, two years later, when her mother, who had been in and out of mental institutions, killed herself. Durst’s mother had fallen — or, he believes, jumped — from the roof of his family’s New York home when he was 7, and the twin tragedies created a bond between him and Berman.

Robert Durst’s lawyer said the real estate heir encouraged Susan Berman to cooperate with the investigation into the disappearance of his first wife, meaning he had no motive to kill the writer in 2000.

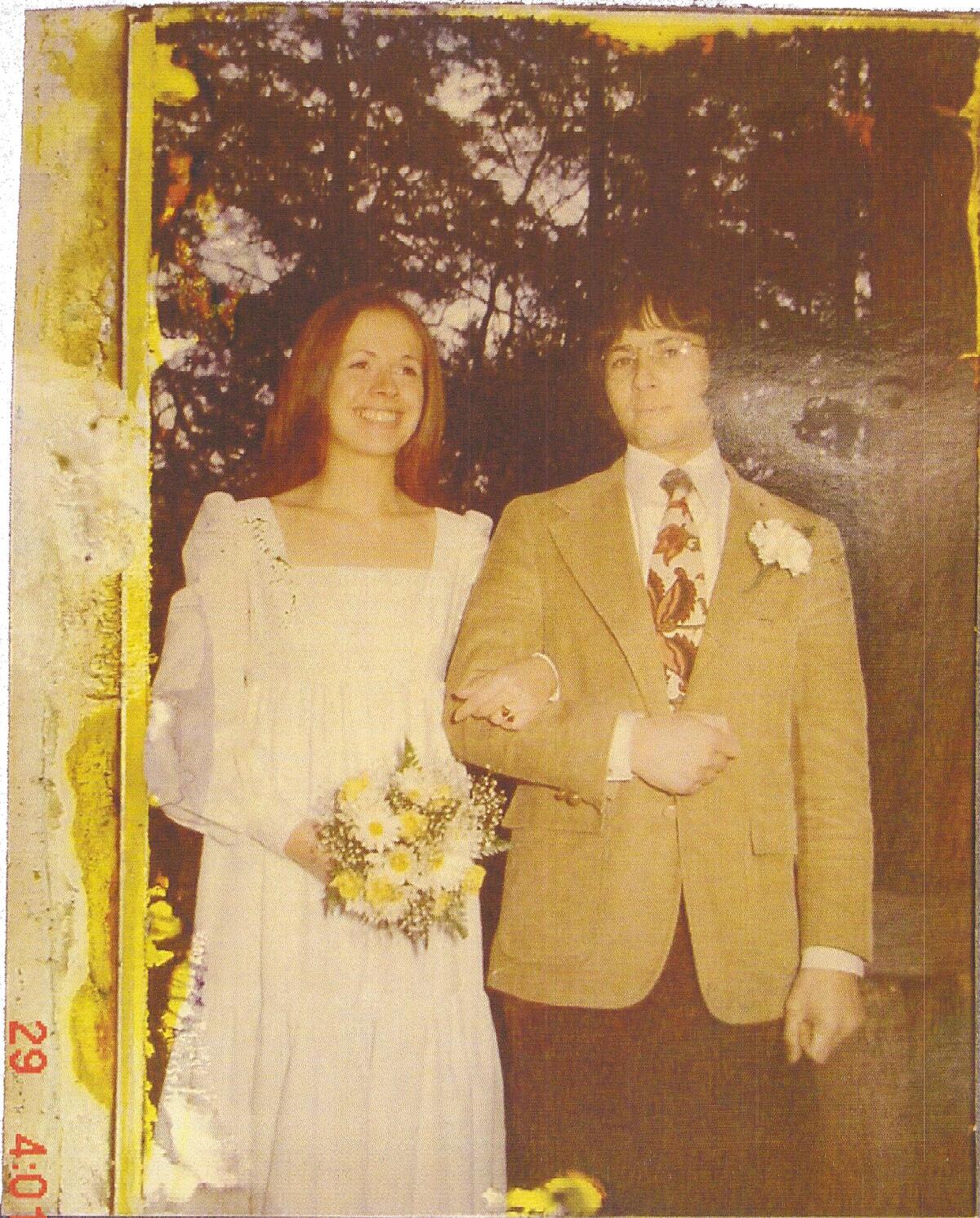

After stints living with an uncle and at boarding schools, Berman moved to Los Angeles to attend UCLA and later became a writer. In 1983, while waiting in line to register a script with the Writers Guild, she spotted a man a decade her junior wearing a faded T-shirt, Ray Bans and a gold ring on his pinkie, according to Berman’s recounting in her book, “Lady Las Vegas.”

“I know you,” the man whispered.

His name was Mister Margulies. He was from Las Vegas, he told her, and his father had adored her father. He was so spectacular, Berman wrote, that she had to marry him. But the marriage quickly fell apart. Margulies later died of a drug overdose.

For years, Berman remained largely, and perhaps willfully, ignorant about her childhood until a roommate’s friend asked what, exactly, her father had done in Las Vegas. He was a hotel owner, she told him, according to a recounting in her memoir.

“That’s not what it said in a book I just read,” the student responded. “It said he could kill a man with one hand behind his back.”

Berman asked for the book’s title and sped to a bookstore on Santa Monica Boulevard, where she tore through the pages until she spotted her father’s name and a reference to Sing Sing prison. She felt sick, telling herself it was just gossip. But Berman, who worked as a journalist, later requested her father’s FBI file and asked a federal employee if the documents indicated whether he had killed anyone.

“Oh, yes,” the woman said, impersonally. “He was a trained killer.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Berman was struck with debilitating migraines and anxiety attacks after learning the truth about her father but soon had a freeing realization: Her loyalty to him was as strong as ever.

Still, the news affected her.

“I am never secure and live with a dread that apocalyptic events could happen at any moment,” she wrote. “Death and love seem linked forever in my fantasies.”

***

In the days after Kathleen disappeared in 1982, reporters began hounding Durst for comments, and he asked Berman to handle the press. She obliged — and, according to authorities and some of Berman’s friends, it wasn’t the only thing she did to help him.

Kathleen’s body has never been recovered, and Durst has never been charged in connection with the disappearance. He has denied any knowledge of what happened to her.

Prosecutors, however, contend that Durst killed his wife, who was planning to divorce him, and enlisted Berman to help with the cover-up. Not long after the disappearance, Miriam Barnes recalls Berman, her close friend, nervously telling her that she’d done a favor for Durst, according to Barnes’ 2017 testimony.

“If anything ever happens to me,” she recalled Berman telling her, “Bobby did it.”

Another friend, film producer Lynda Obst, testified that Berman explicitly told her that, as a favor to Durst, she’d called New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine pretending to be Kathleen.

In the months preceding her death, friends say, Berman grew increasingly desperate about money and resorted to selling her mother’s jewelry. She hit up Durst for cash, and he mailed her two checks, each for $25,000. One of her friends would testify that during a dinner in Santa Monica on Dec. 22, 2000 — one of her final meals — Berman griped about her landlord, who had wanted to evict her.

Then, on Christmas Eve in 2000, after neighbors spotted her dogs running loose, police arrived and found Berman’s back door ajar. In the doorway of one of the bedrooms, they found Berman’s body with a single bullet through the back of the head. She was barefoot, and her purse was on the counter. Nothing had been taken.

Suspicion initially fell variously on her landlord, her business manager and the underworld crime syndicate. “Screenwriter’s death a mob hit?” one headline mused.

***

The investigation into Berman’s murder was cold for years and, if not for Hollywood, might have stayed that way.

In the film “All Good Things,” a fictionalized character, played by Ryan Gosling and loosely based on Durst, is tied to the slayings of his wife, his best friend, his neighbor and his dog. Prosecutors said that after the movie was released in 2010, Durst contacted director Andrew Jarecki, offering praise and a single criticism — he didn’t like the depiction of killing the dog.

The two men stayed in touch and Durst agreed, against his lawyers’ advice, to sit for taped interviews for the six-part documentary “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst.”

With jury selection set to begin in Los Angeles on Wednesday, the Robert Durst murder trial is expected to last up to five months, pitting a lineup of elite Los Angeles County prosecutors against the high-end Houston legal team that helped Durst beat a murder charge in Texas in 2003.

On March 14, 2015, a day before the finale aired, Durst was arrested in connection with Berman’s slaying at a hotel in New Orleans, where officials found guns, a fake ID and a mask. The arrest was “urgent,” prosecutors said, because of “damning evidence” in the last episode.

In the finale, Durst, wearing a microphone and apparently unaware he is being recorded, mutters to himself during a bathroom break: “What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course.”

Many viewers took the comments as a confession to the murders of three people: his wife, Berman and Black. But it would later emerge that parts of the raw audio were edited and the statements spliced together out of order.

After his arrest, Durst sat for a recorded jailhouse interrogation with Los Angeles County Deputy Dist. Atty. John Lewin. At one point, when the prosecutor described Berman as someone Durst cared about, the millionaire chimed in, saying, “Best friend.”

“I’m gonna just ask this straight out,” Lewin later said. “If you had killed Susan, would you tell me?”

No, he answered.

Two years later, Obst, the film producer, testified at a pretrial hearing about her friend’s complicated loyalty to Durst.

Berman compared things she’d done for “Bobby” to the way her mother showed her father love by keeping his secrets, Obst said.

“If you could be loyal to somebody,” Berman told her, “that was love.”

Lewin asked Obst if there was someone whom Berman seemed more loyal to than anyone else.

“Yes,” Obst answered. “Robert Durst.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.