Witness in Robert Durst murder case testifies he suspected the victim’s manager in the slaying

- Share via

One of the last known people to see writer Susan Berman alive in 2000 testified Monday that he had suspected her manager in the slaying, which prosecutors say was committed by her best friend, New York real estate scion Robert Durst.

Richard Markey said that Berman, his friend, had a “turbulent” relationship with her manager, Nyle Brenner. After the killing, Brenner told him he didn’t plan to cooperate with authorities, Markey said.

The testimony came during a hearing in a Los Angeles courtroom during which several witnesses, including Durst’s high school classmate turned personal attorney, are scheduled to testify for the prosecution.

Prosecutors say the 74-year-old multimillionaire — whose navy suit jacket hung from his frail frame Monday — shot Berman inside her Benedict Canyon home in 2000 to silence her for knowing too much about the 1982 disappearance of his wife, Kathleen.

Berman, who was the daughter of a Las Vegas mob boss, met Durst in the 1960s while both attended UCLA and had acted as his unofficial spokeswoman after the disappearance.

Durst has pleaded not guilty and says he doesn’t know who killed Berman. Because his trial is unlikely to start before at least 2018, prosecutors have called several elderly witnesses ahead of time to preserve their testimony. Monday’s proceeding began the fourth round of such hearings — called conditional examinations — in which witnesses are videotaped while testifying.

Markey, 69, described Berman — whom he met while picketing at a writers strike in 1988 — as someone with an insatiable curiosity, vast knowledge of esoteric historical facts and a lot of phobias. Berman, he said, was “extremely security-conscious,” adding that even when she knew he had plans to visit her, she’d always peek out the window and then ask, through the door, who was there.

When Deputy Dist. Atty. Habib Balian asked Markey if he thought Berman — who was shot inside her home — would’ve unlocked the door for a stranger, Markey said no.

“She had a phobia about things like that,” he said.

Markey also testified that Berman told him that Durst had sent her two checks — each, he thought, for $25,000 — in the month or so before her death.

On Dec. 22, 2000, Markey said, he went to dinner and a movie with Berman at the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica. Over the meal, they spoke about a lot of things, including Berman’s frustrations with her landlord.

“Susan had been essentially at war with her,” Markey said, adding that Berman had been overdue on rent. But the problem had been resolved, Markey said, noting that he thought Berman had used the money from Durst to pay her rent.

After watching “Best in Show” that evening, Markey said, Berman took him home. And since she knew he was headed to Las Vegas for a family reunion, she gave him the address of a home she’d once lived in and told him to drop by if he had the time. She then drove off, he said, and he never saw her again.

When he returned from his trip, Markey said he had a phone message from Brenner, the manager, saying Berman was dead and that the police would probably be contacting him.

Under cross-examination by Chip Lewis, one of Durst’s attorneys, Markey said Berman and her manager had “a love-hate relationship,” adding that Brenner was often frustrated by Berman’s demands.

“He certainly carried the brunt of her anxieties,” the witness said.

Markey said he eventually returned Brenner’s call and said his friend’s manager told him to expect the police to pry into his life, warning Markey to protect himself.

Did Brenner’s comment seem strange, the defense attorney asked? “Yes,” Markey responded.

When the defense attorney asked Markey if Brenner had ever told him that he’d sneaked into Berman’s home after the killing, Markey initially said he didn’t recall, but then added that he did remember the manager saying something about seeing fingerprint dust inside Berman’s home. The manager also told him, Markey testified, that police wanted his phone records, but that he didn’t plan to cooperate.

“Is it fair to say,” Lewis asked, “you were suspicious of Mr. Brenner’s involvement in Susan’s death?”

“Yes,” Markey said. (Authorities once considered Brenner a potential suspect.)

Markey also testified that after Berman’s memorial service he’d gone to lunch with Durst — who didn’t attend the service — and a mutual friend. Durst, he recalled, said he hadn’t attended because he didn’t want to create a media circus. Over lunch, Markey said, Durst didn’t seem concerned about what happened to Berman, focusing instead on how he was being hounded by a prosecutor in Westchester County, N.Y., who had reopened an investigation into his wife’s disappearance years earlier.

After Markey’s testimony, prosecutors began questioning Berman’s former boyfriend, Paul Kaufman, who described Berman as an extremely generous person, who became a surrogate mother of sorts to his two children.

Kaufman, 74, testified that on a plane ride to New York years ago with Berman, she told him that Durst killed his wife. The topic came up, Kaufman testified, because he and Berman were discussing murder scripts and mobster ideas.

“She said, ‘By the way, you know, Mr. Durst killed his wife,’” Kaufman testified. He said he wasn’t sure if what she’d said was true as it had come up while they’d been “talking about imaginary circumstances.”

When the prosecutor asked him if he’d asked Berman how she knew this, he said, “No, I did not at the time…. I did not particularly believe it or disbelieve it.”

Asked by another of Durst’s attorneys, David Chesnoff, whether it would be true to say that he took the comment “with a grain of salt,” the witness responded: “This is true.”

“She was capable of saying all kinds of things — that was part of her charm,” Kaufman said, adding that Berman sometimes embellished facts.

Kaufman also testified that when he heard about her death, his first thought was that she might have been killed by a Las Vegas mobster.

After Chesnoff finished questioning the witness and returned to his seat, Durst extended his arm.

“Thank you,” the defendant said, shaking his attorney’s hand. “That was very good.”

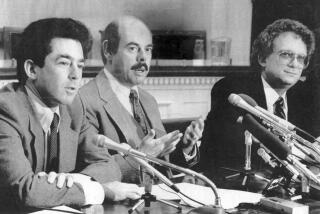

On Tuesday prosecutors plan to question Stewart Altman, a labor lawyer who went to high school with Durst in Scarsdale, N.Y.

Prosecutors will probably question Altman about a phone call he had with the defendant years ago. During a hearing last month, prosecutors played a clip of a “Dateline” television episode, which featured Altman talking about a call he received from Durst, who at the time was jailed in Galveston, Texas, pending trial in the killing of his neighbor, Morris Black. (Durst admitted shooting Black and then chopping up his body, but argued that he’d accidentally shot him in self-defense during an argument. He was ultimately acquitted.)

“He said he went to a fugue state,” Altman told the reporter, quoting Durst. “It’s hard to understand.”

Last month, Altman’s wife, Emily, testified that Durst once told her that he’d been in Los Angeles around the time of his best friend’s murder. She said she believed he’d stayed at the Beverly Hilton. The hotel, a prosecutor told the judge, is less than three miles from Berman’s home. Her testimony provided a key piece of evidence, as investigators had struggled to put the millionaire in L.A. at the time Berman was killed.

But under cross-examination, Emily Altman ultimately backtracked, saying that she couldn’t recall if she’d heard the information directly from Durst or from her husband and that she wasn’t sure if Durst had been in Los Angeles or merely in California. She testified that after giving her initial testimony she spoke with her husband, who told her that he believed she was mistaken about the conversation.

Defense attorneys, as well as Stewart Altman’s personal attorneys, have objected to the questioning, citing attorney-client privilege for himself and his wife, who is the sole employee at her husband’s law firm.

In a letter to prosecutors late last year, Altman’s attorney, John Macklin, said that his client began working as a personal lawyer for Durst in 1969 and any communication they’d had since then was protected. Emily Altman testified last month that although her husband wasn’t part of the trial team in Galveston, he had been retained as Durst’s attorney at that time and often spoke with members of the trial team.

The hearing is expected to last several days.

For more news from the Los Angeles County courts, follow me on Twitter: @marisagerber

UPDATES:

4:30 p.m.: This article was updated with more details from Monday’s testimony.

2:25 p.m.: This article was updated with details from Monday’s testimony.

This article was originally published at 5 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.