Sick of loud noises and bright lights? Sorry, L.A. has always been like that

- Share via

Lights and sirens! Bells and whistles!

Today, Los Angeles fills your ears and eyes with noise and light, the rush and whoosh of cars and buses and trains, the pinging and ringing of millions of phones, the music that’s not to your liking leaking from other people’s earbuds, and the perpetual glimmer and glare from headlamps and streetlamps and storefronts.

And oh, are you ever wistful for the years of yore, for a Los Angeles that surely cherished civilized silences and decent darkness.

Boy, have you got the wrong place.

That L.A. was definitely not taking vows of silence, or dimness. Factory steam whistles, air raid sirens, streetcar bells, bakery deliverymen and traffic cop whistles, gas-pump chimes, flashing civic beacons, twirling lighthouse lamps and even, for some years, the Hollywood sign: Los Angeles loved it some electricity.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

As for the decibel clamor — that was the barter deal for a bigger, better L.A.

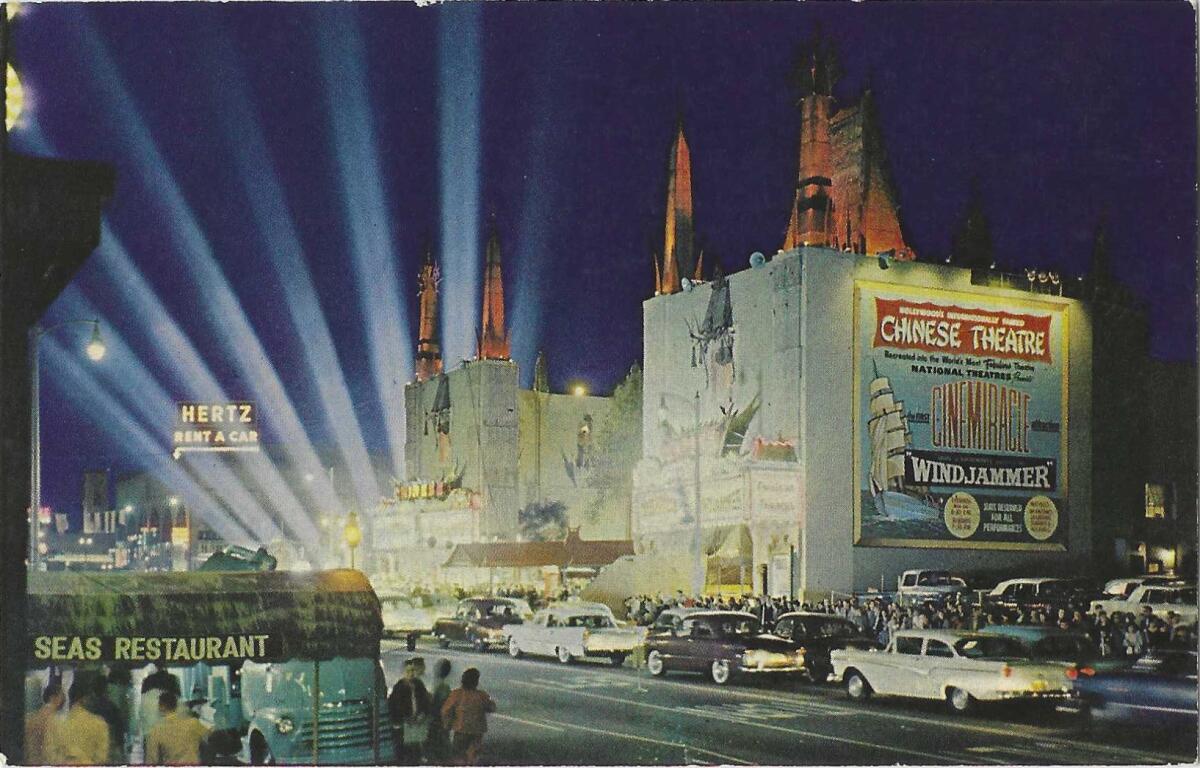

There is no way I’m getting myself into hot Perrier by calling L.A. the “city of light,” but one glimpse of Klieg lights combing the night sky and “Hollywood premiere” is the right answer. In October 1923, a year after probably the first gussied-up Klieg-light premiere — “Robin Hood” at the Egyptian Theatre — a Times critic wrote, “Whoever started the business of banking theatres with lights at openings certainly owes a free seat to the traffic commission” for its crowd control services.

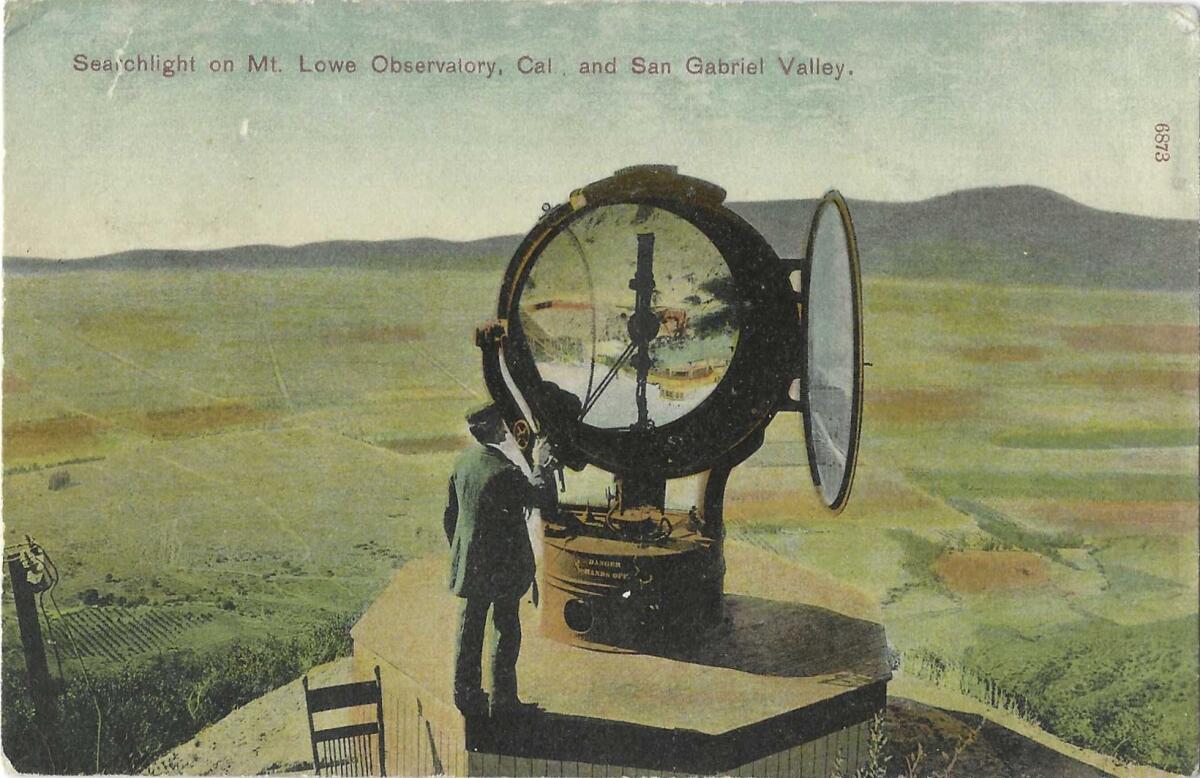

The world’s biggest searchlight first blazed forth at Chicago’s world fair in 1893, but the next time it opened its three- (or six- or 375-) million candlepower eye, it was on top of Echo Mountain in the San Gabriels, bought by the eccentric entrepreneur Thaddeus Lowe for his Mt. Lowe resort. Lowe’s publicist declared that when the lamp gazed out across L.A., you could read the newspaper on Catalina Island, 60 miles away, by its light. By the 1930s it had been shut down as a nuisance, its whereabouts now a mystery that needs solving.

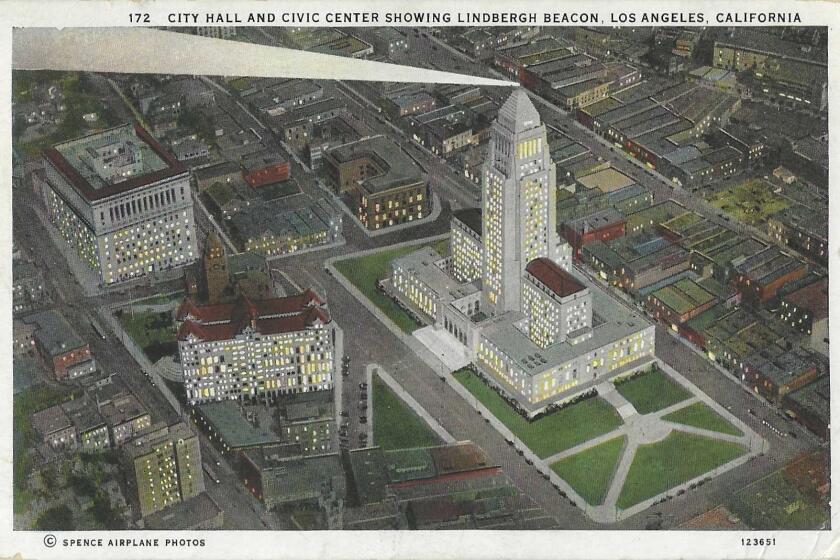

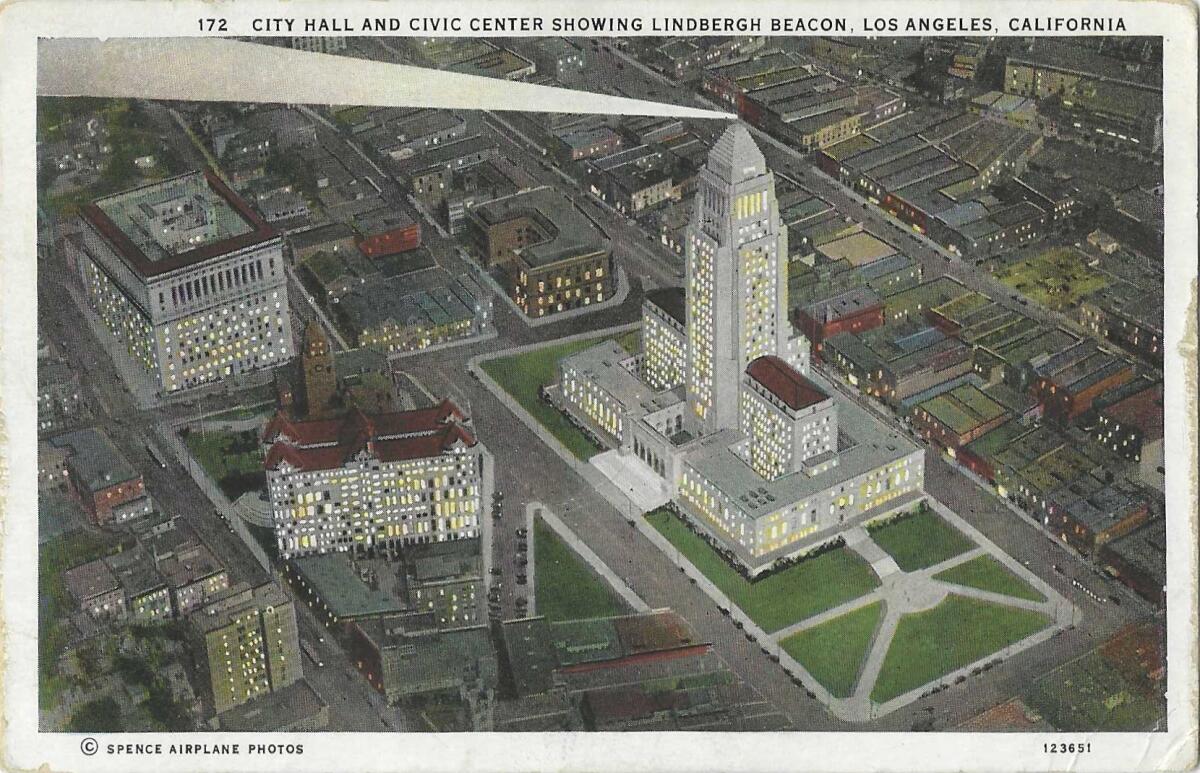

Its place as L.A.’s sky-piercing beam was taken by the Lindbergh beacon atop L.A. City Hall. It was named for the “lone eagle” aviator Charles Lindbergh and activated in 1928 by President Coolidge pressing a gold key in the White House. The tallest building in L.A. streamed the strongest light in L.A. for 60 miles in any direction, revolving six times every minute.

Act II: Six months after the light was switched on, Lindbergh’s business partner told the press that he and Lindbergh had flown here from Kansas and been forced to buzz around nighttime L.A. for hours looking for a place to land, after they realized the Lindbergh beacon was nowhere near a landing field. “Instead, all I saw were rooftops and gas tanks,” Lindbergh said then.

If that weren’t a blow enough to civic pride, the federal government then insisted the city could not use a white light in the beacon. For safety reasons, it had to be crimson, the lurid hue of brothel lights.

The whole operation was shut down by Pearl Harbor, and restarted in 1947, with three lights. One, “Mr. Los Angeles,” blinked out “L A” in Morse code over and over, for wayward pilots. A second light beamed a Hollywood-scale cone of light toward the L.A. airport. And the Lindbergh beacon revived its revolving multimillion-plus-candlepower beam. (Today you can put a 40-million-candlepower lantern in your online shopping cart for a few hundred bucks.)

At some unknown moment, and for an unknown number of years, the beacon was unplugged and cached away in the City Hall basement like Charles Foster Kane’s sled, Rosebud. Some time in the 1990s, it was put on display — still unplugged — at the Tom Bradley terminal at Los Angeles International Airport.

In 2001, as part of a major City Hall restoration, it was brought back to the top of City Hall to be re-lighted, with a white light, and with the FAA’s approval, on very special occasions. One was the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks; others were the 2014 and 2015 December holiday seasons.

And I wonder how long before it gets renamed. Lindbergh, the brilliant aviation pioneer of the 1920s, became the admirer of Nazi Germany and eugenics philosophy of the 1930s — he sounded Proud Boyish when he wrote of “the infiltration of inferior blood” into the West — and the isolationist of the early 1940s, until Pearl Harbor silenced him as surely as it shut down the Lindbergh beacon.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

Now, the Hollywood sign was originally lighted up, of course, because how could L.A. ever pass up an opportunity for excess?

The 1923 “Hollywoodland” hillside ad for a real estate development flashed with 4,000 20-watt lightbulbs — first the “HOLLY” part, then “WOOD,” then “LAND,” and lastly, all together now, “HOLLYWOODLAND,” over and over. So classy.

The dogged caretaker, Albert Kothe, regularly labored up the steep hillside with a load of gently tinkling replacement lightbulbs buttoned inside his shirt. When the city took over the sign in 1949, the lights went out and the ‘LAND” part was taken down – which was wise, because, left to the elements, collapsing letters might have left the sign spelling out haphazard unpleasantries like HOLY ODD or HOOD LAND.

(Last week’s hanging of a cow’s face over the first “O” was one more swing at immortality and a criminal record in the decades of people pranking the sign, a history too long and digressive for here. People never stop trying to do it. And the cops never stop arresting them for trespassing. By the way, it’s hard to tell for sure from the photos, but I believe, city people, that the cow in question is a Holstein.)

It’s been lighted up rarely since then, once for the 1984 Olympics, and again for New Year’s Eve 1999, which entangled traffic so badly that some people who live below the sign now fight like Cossacks any time someone suggests lighting the thing up again.

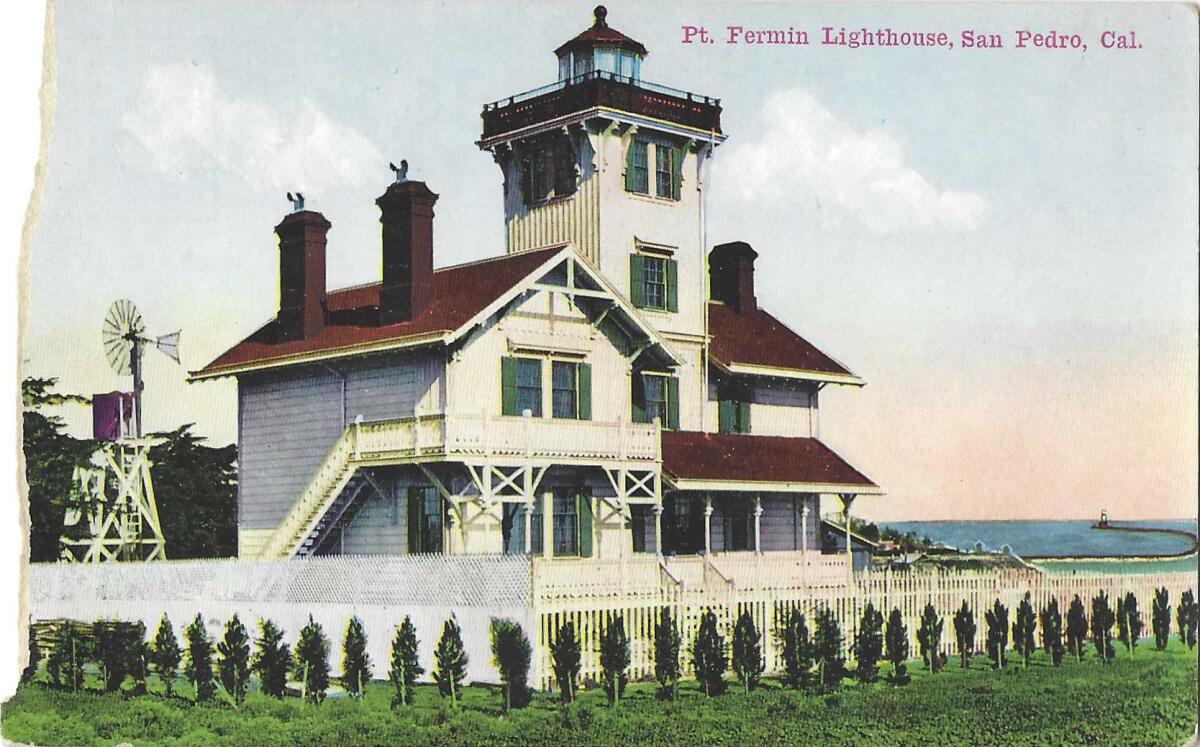

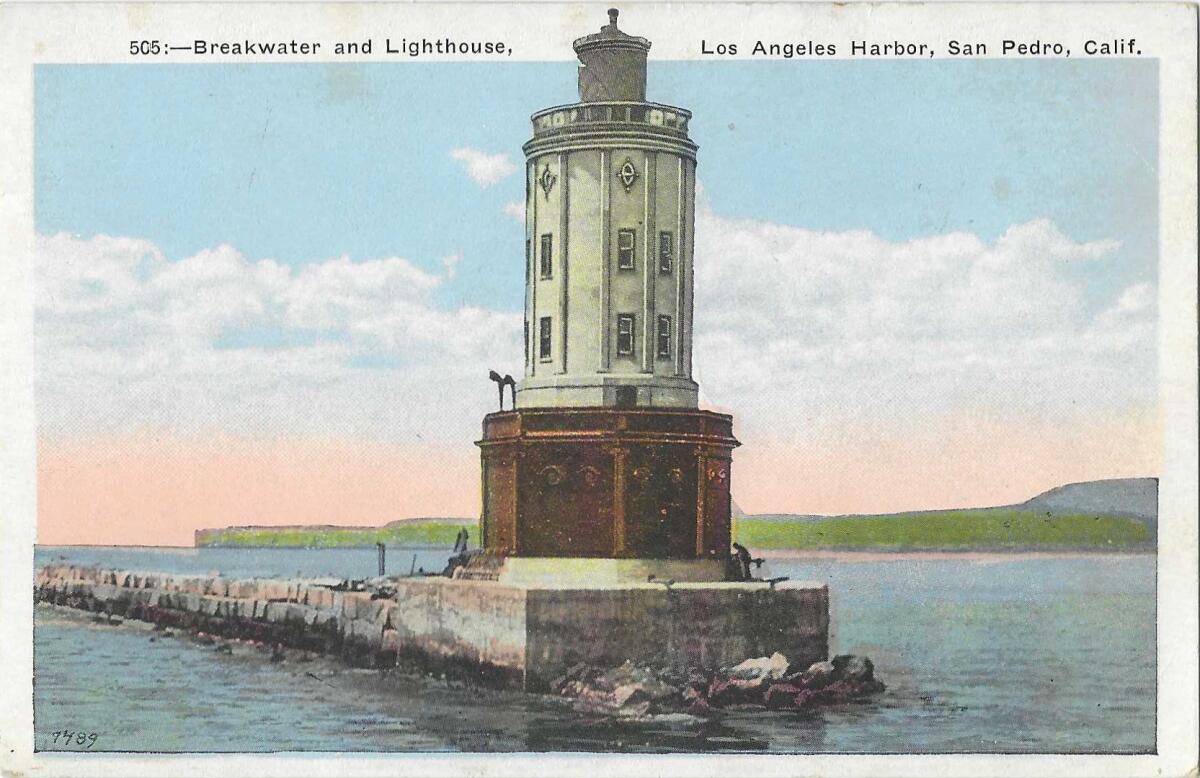

Far from Hollywood’s ornamental lights are working-class lights, lighthouses ranged around the Los Angeles-Long Beach harbor, the busiest harbor in the nation. They’re like the siblings in some 19th century novel.

The eldest, the Point Fermin lighthouse in San Pedro, is nearly 150 years old and retired from service but still cute as a button. Its first keepers were a pair of sisters. Its light was blotted out during World War II and never came back on thereafter.

Point Vicente, the family beauty, stands atop the cliffs of Rancho Palos Verdes, 95 years old but not looking its age, and like most modern lighthouses, now operated remotely, no longer by some screenplay-ready morose lighthouse keeper and his unfulfilled wife. Like the irritated neighbors of the Hollywood sign, RPV’s prosperous insomniacs grumbled about the pulsing nightlong twirl of light, and so the inland side of the lamp was painted opaque white, and the foghorn was silenced early in this century.

The youngest is the one sibling who never looks like the other kids: the 1949 “baby boomer” Long Beach harbor lighthouse, the “robot light,” stocky and square as a wrestling champ, a solar-powered bunker on legs. Even a website devoted to loving lighthouses admits that it has to be California’s ugliest.

And then my favorite, the harbor lighthouse, Angels Gate, 73 feet high, defying the bullying seas since 1913 at the end of a nearly two-mile-long stone breakwater. Its revolving illumination is an extremely rare emerald-green light, making me think of the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock that Jay Gatsby mooned over.

Lighthouses create son et lumiere, sound and light; it’s their job. Noise was the outward and visible sign of an industrious L.A. Yet in 1890, The Times pleaded in nice, quiet ink: “Why should the barbarism of the steam whistle and the noisy ‘bells jangled out of tune and harsh’ be longer continued? … a good time-piece can be had for less than a dollar … the majority of the workers of the world manage to get to their daily tasks without the steam war-whoop of a triple whistle or the clang of a brazen bell.”

Steam whistles shrilled over the landscape, summoning workers to make bricks, process sugar beets, assemble guns and craft airplanes. In spite of its editorial, The Times kept a steam whistle onsite “to indicate important events.” In November 1928, every factory whistle and siren and chime in the city was enlisted to sound every hour to remind workers, once they were freed from factory and office, to go vote. (And then hurry home to cover your ears with your pillow.)

In 1904, L.A. imposed a 9 p.m. under-18 curfew, which to my knowledge has been modified to 10 p.m. but never lifted. The curfew shriek of the gas company’s commanding steam whistle on Ramirez Street sent kids racing home. In 1915, two little boys, 8 and 12, were scooped up off the street at 9:30 p.m. Please officer, they pleaded, their mothers had gone to a meeting and left them at the moving pictures and then the picture had just let out.

A more welcome whistle for almost 40 years was the two short, sharp whistle toots announcing the arrival of the Helms bakery deliveryman bearing bread and jelly doughnuts and cream puffs. In July 1969, Helms bread went to the moon with the Apollo astronauts. Five months later, Helms shut down its ovens, surrendering to the car and the supermarket.

Streetcar bells were the metal engine bells and electric bells rung by a crew member The Times insisted on calling the “motorneer.” People on foot didn’t always hear or heed them, and judging by the headlines, streetcar carnage was considerable. In 1905, the red car waiting room at the station at Sixth and Main replaced its departure “annunciator” electric bell with “sweet-toned triangles of steel,” and put one in the women’s waiting room too.

Modern-day L.A. metro rail trains use an orchestra of horns and gongs to announce themselves.

Until December 1941, sirens in L.A. were what you heard from fire engines alerting you to their coming. City and county governments soon, very soon, bought more hundreds of air raid sirens, installing them at the Griffith Observatory, UCLA’s physics building and all points of the compass. For 40 years after the war’s end, every Friday at 10 a.m., the sirens still warbled across L.A., testing their readiness and ours for nuclear attack. They failed. Almost a third of them were broken, and in 1985 the county voted to unplug its sirens.

In late December 1941, within three weeks of the Pearl Harbor attack, City Council members bravely declined to put cotton in their ears and gathered to listen to siren salesmen’s sales pitches, to decide which model the city should to buy.

They tended to favor one whose sound could carry seven miles on a clear day and three miles on a windy one. This was a proven fact because the siren was already being used at Fish Harbor, a manmade island settlement in San Pedro, to summon cannery workers when the fleet came in loaded with fish.

Until Dec. 7, 1941, those cannery workers who were summoned by that siren had been Japanese and Japanese Americans.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.