Commentary: We lost two of the three great L.A. Toms on the same day. Here’s what they can teach us

- Share via

A story of Los Angeles in three acts, all of them named Tom.

Two of these Toms died on the same night last week.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Tommy Lasorda was 93, the Dodgers’ manager emeritus, the man who bled Dodger blue since Brooklyn. Tom LaBonge was 67, a city aide, a mayor’s deputy, a councilman and eternally a groupie for the city that LaBonges have called home since at least 1901, when a barber named LaBonge served on the jury for a Chinatown murder.

The first act in the play belongs to the Tom who was so preternaturally dignified that it was always startling that this august man should have gone by the nickname and not his given name, Thomas — Tom Bradley, the first Black mayor of Los Angeles.

Bradley was an LAPD cop who labored to reform the department that had not let him or any Black officer partner with a white one; a 20-years’ resident of the mayor’s official mansion in Windsor Square, a neighborhood where, 40 years earlier, he would not have been legally allowed to live except as a servant; the grandson of slaves who signed a decree to end discrimination at influential private clubs where every mayor had received a courtesy membership — until Bradley.

Connect these three Toms and you have the three magi attending the birth of a new Los Angeles, an ecumenical place, a confident place, a city no longer a Hollywood coat-holder or New York also-ran.

From Bradley, we became a Los Angeles that was no longer a parochial backwater, but a world-class city to be reckoned with, a majority-white city that could elect a Black mayor. Jimmy Carter offered him a Cabinet position; take that, Chicago! Walter Mondale interviewed him — perfunctorily, true — for vice president. How’d you like them apples, Ed Koch?

The low point for his long tenure was the 1992 riots; they gutted the city and the heart of its mayor. The apogee was the 1984 Olympics, Games L.A. won by default but performed with splendor. Tom Bradley, the UCLA track star, the sharecroppers’ son who at 14 peered through the Coliseum fence to watch the 1932 Games, presided over the 1984 Games with a delight that lit up the face of the man known as the “Sphinx of Spring Street.”

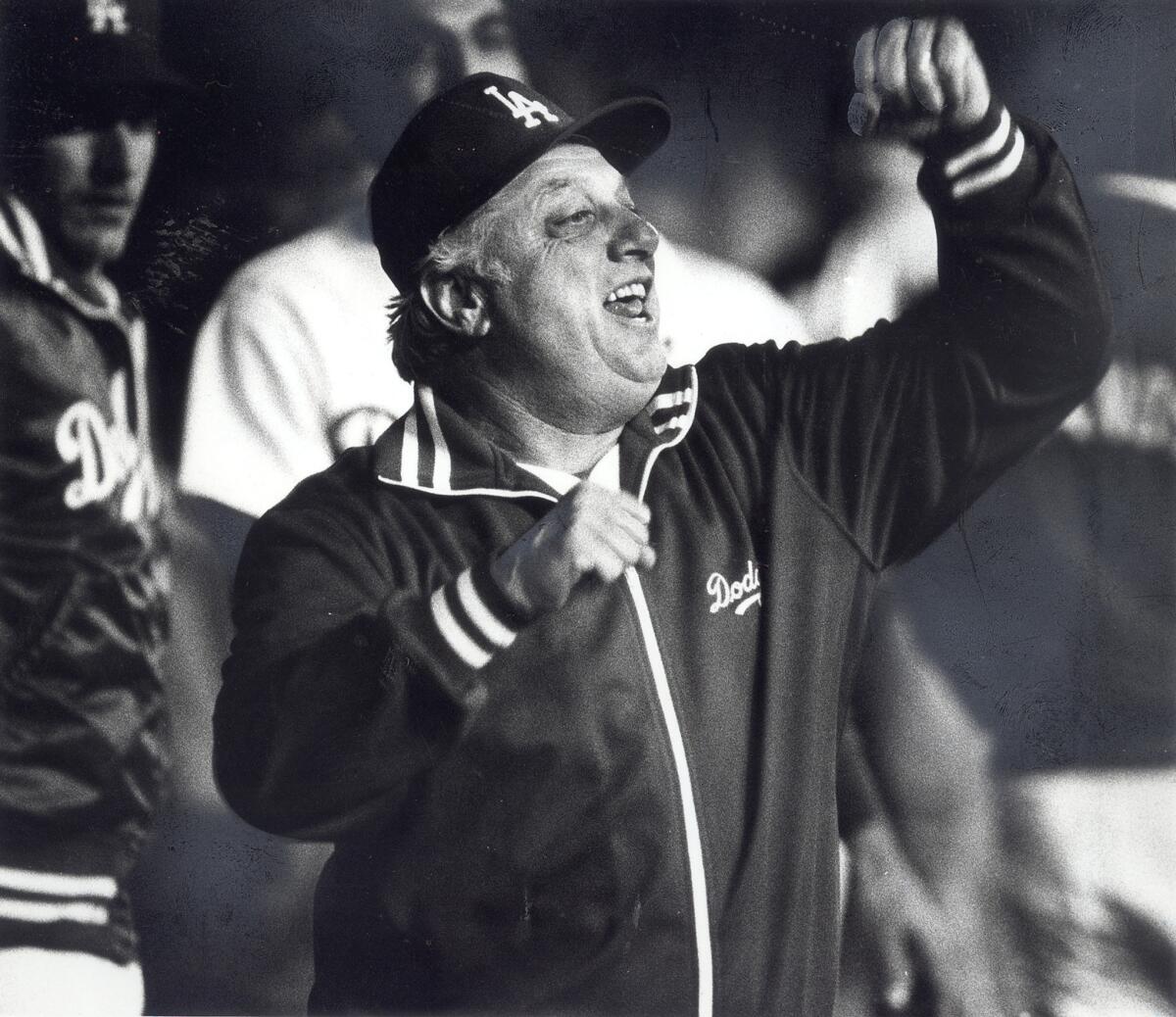

From Lasorda, we got the gift of a love not just for a sport but for a home team and its home town. Lasorda spent 71 years as a Dodger, on that coast and this one, in virtually every job but batboy. He turned down other work, doggedly waiting to manage the Dodgers. His team monogamy, the force of his personality and his winning record made a sports world still moping like a diva over Dodgerless Brooklyn sit up and take notice of this West Coast team.

The Dodgers made Los Angeles think better of itself, too — made it regard itself as one city, a major-league city. In 1959, when Vin Scully announced on a zillion car radios the 12th-inning run that guaranteed the Dodgers a trip to the World Series, the car horns bleated in chorus from the harbor to the Valley to the Eastside.

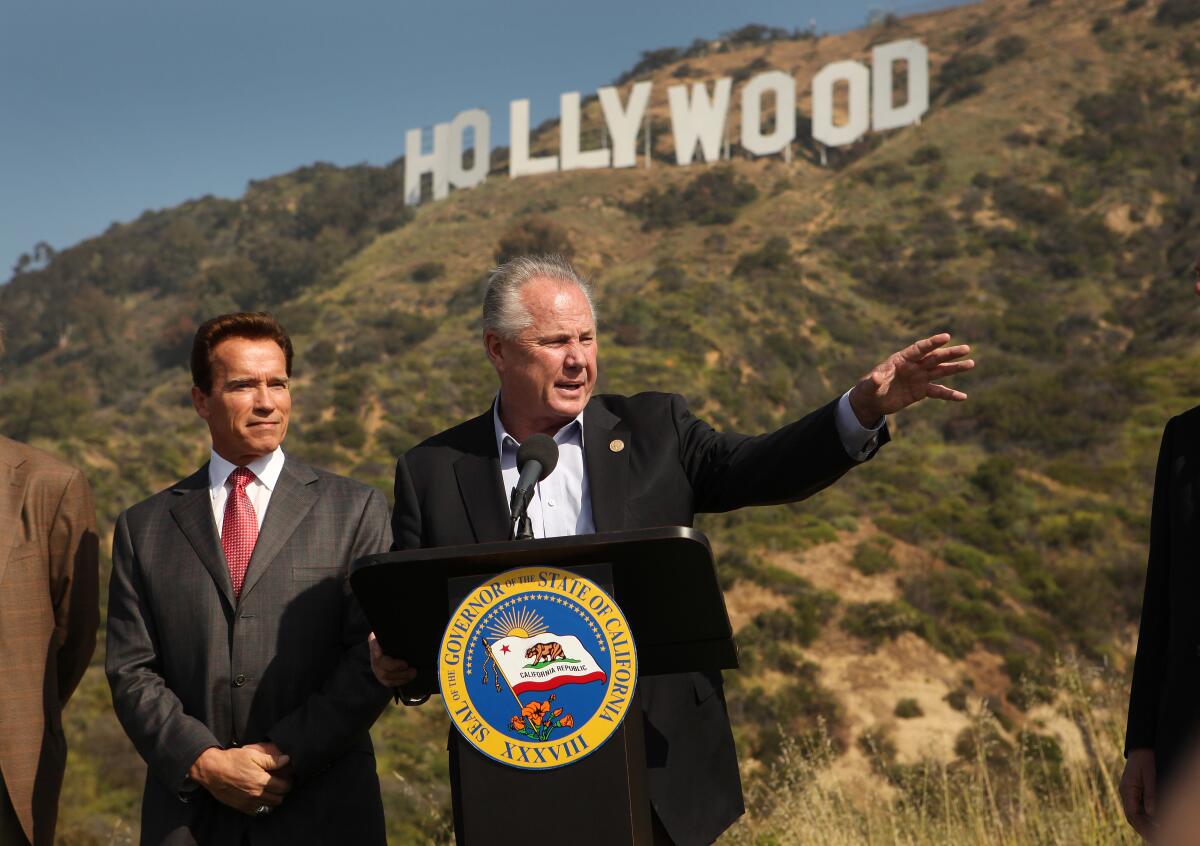

From LaBonge, we were charmed by a boyish Pangloss who believed passionately that the City of the Angels was the best of all possible places. L.A. was forever a small town to him, and in the face of too many years of Angelenos’ cynical, hangdog inferiority complex, he exhorted us to love L.A. warts and all, to rejoice even in its crazy ugly bits.

His artless goofiness annoyed the hell out of some of his city colleagues but amused most everyone else. Once, he ordered his staff to find Eric Garcetti via Blackberry, but it came out, “Jellybean him!”

Before he became a council member himself, he worked for a council member, and for two mayors, one of them Bradley, so of course he wanted to be the mayor of so fabulous a city. In his mind, he couldn’t imagine anyone not wanting that. But in truth, he wanted it not to set grand policies nor to fulfill a vision. No, he wanted it the way a kid wants to be a ballplayer or a rock star, for the matchless fun of it.

Each of these Toms has, to a larger or lesser extent, a solid claim to being “Mr. Los Angeles,” but it is as a triumvirate, like the enchanted trio of wishes in fairy stories, that they all — just like a team does — gave Los Angeles what it needed most from them.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.