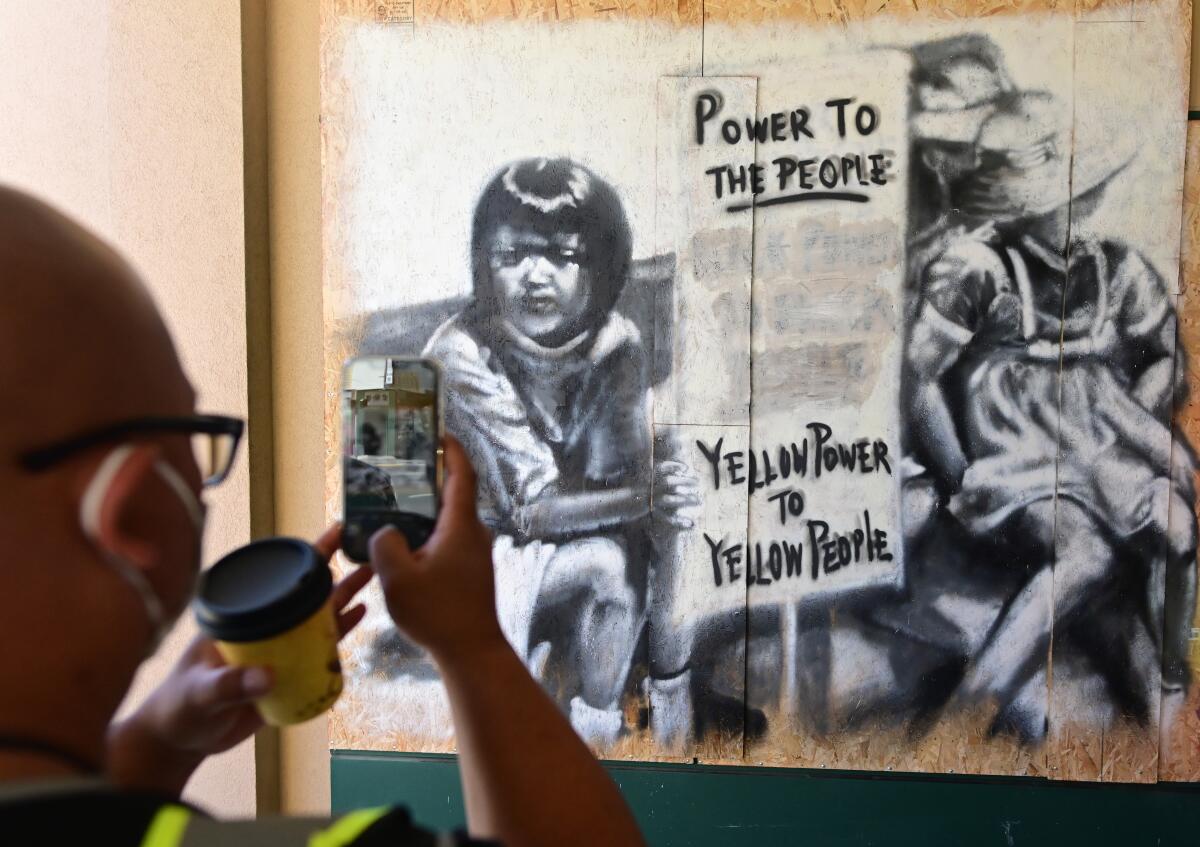

After attacks on Asians in Oakland’s Chinatown, volunteers offer protection and support

- Share via

OAKLAND — As the volunteers assembled to patrol a neighborhood rattled by violence, Katrina Ramos gave a quick tutorial.

People who need help will not always say so, she said.

Study their faces — do they look lost or confused? Maybe a senior citizen carrying heavy groceries might appreciate you hovering nearby, said Ramos, co-founder of Compassion in Oakland.

About 30 volunteers showed up on a recent Saturday afternoon to accompany pedestrians to their destinations in Oakland’s Chinatown after a spate of attacks on elderly Asian Americans.

Even before a gunman killed eight people, including six women of Asian descent, at spas in the Atlanta area on Tuesday, Chinatown was on edge, its dim sum cafes and jewelry stores decimated by the COVID-19 pandemic, its residents in constant fear that an assailant might sneak up behind them.

Authorities said there was no proof that the attacks were racially motivated. But the vulnerability of the victims, combined with a national rise in anti-Asian hate crimes fueled in part by the coronavirus’ Chinese origins, had many people asking: What can I do to help?

Horrific videos of Asian American senior citizens being shoved to the ground while walking down the street have inspired even those with no personal connection to Chinatown to work a shift or two with one of about 10 groups that have sprung up in recent months.

Similar patrols are assisting seniors in San Francisco and San Jose.

Compassion in Oakland, which formed in February in response to anti-Asian attacks, plans to start working in the San Gabriel Valley as soon as next month, and a group has been soliciting volunteers for Los Angeles’ Chinatown and Little Tokyo.

Language barriers can make it challenging for volunteers to communicate with the people they are trying to help. Usually, the volunteers have no special expertise or equipment. They hope their mere presence will deter attackers.

Since the Atlanta shootings, some law enforcement agencies, including the Los Angeles Police Department, have increased patrols in Asian communities. In February, Oakland assigned a Cantonese-speaking officer back to Chinatown after previously eliminating the position.

The Compassion in Oakland volunteers came from a mixture of backgrounds, they were different ages and spoke different languages.

Each group of three or four would include a Mandarin or Cantonese interpreter and would patrol the streets as well as chaperone people who called a hotline.

One volunteer said he had not heard about the attacks until seeing on the news that Taiwanese American pro basketball player Jeremy Lin was called “coronavirus” on the court.

Another said friends of Asian descent have told him that their parents “do not feel safe going out — period.”

“The violence is popping up in unexpected places, and people aren’t going to sit silent anymore,” said Ramos, 26.

Before the nation’s attention shifted to Atlanta, the Bay Area had become a hot spot of violent crimes against Asian Americans, as verbal and physical racist attacks escalated nationwide during the pandemic.

Some of the attackers have struck seemingly out of nowhere.

In San Francisco in January, an 84-year-old Thai immigrant died after he was shoved to the pavement by a man who suddenly approached him, then walked briskly away, surveillance footage showed.

On a sidewalk in Oakland’s Chinatown that same month, a man in a hoodie walked up behind a 91-year-old man and shoved him, leaving him lying crumpled face down.

Arrests have been made in both attacks, with the Oakland suspect accused of two other similar attacks on the same day. It is not clear what motivated the attackers.

This week, more elderly Asian Americans were attacked in San Francisco. One woman fought off her assailant on Market Street with a cane, sending him away on a stretcher.

Senior citizens who have relished the Oakland Chinatown’s pedestrian-friendly environment and Chinese-speaking merchants, doing their own shopping and stopping to chat with friends playing badminton or mah-jongg in the park, are now watching their backs.

“The problem with Chinatown is it’s an enclave,” said Sonny Le, who has lived in Oakland for 40 years and is an activist and Vietnamese interpreter for seniors. “Like other enclaves, community members have shown that they could live their whole lives here without speaking English. Asians become easier targets because one, they lack language ability, and two, they don’t call the police.”

Le, like many longtime citizens, stressed that there has “always been crime, always constant tensions in our beloved city,” adding: “Many residents must now fend for themselves, including pooling money to hire private security guards to patrol their neighborhoods.”

Alicia Wong, 25, said her family’s cookie company has had to adapt to the pandemic at the same time that people they know in the small, close-knit community have become victims of the increasing street violence.

“There is fear,” Wong said. “My parents hear people talk about so-and-so’s uncle getting mugged, and then someone else is targeted.”

Fronted by a large panda mural, Oakland Fortune Factory on 12th Street is the oldest fortune cookie company in the Bay Area, according to Wong.

With the special events business at a standstill and restaurants struggling, the company is offering curbside pickup and creative twists on the traditional fortune cookie.

Inspired by the George Floyd protests last summer, Wong and her husband, Alex Issvoran, have been selling Black Lives Matter fortune cookies with quotes from civil rights leaders and poets, instead of cryptic predictions, tucked inside.

Like many big cities, Oakland has seen a significant increase in some types of violent crime during the pandemic.

In 2020, homicides were up nearly 40% over the previous year, and assaults with a firearm were up 71%.

Officer Mae Phu returned to the Chinatown beat last month, amid the crime increase and fears about anti-Asian racism, after the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce lobbied to reinstate the position.

She works a foot patrol and is a liaison with the community, using her fluent Cantonese to help residents apply for city permits while cracking down on issues such as illegal gambling and parking violations. Her supporters say her language skills and ties to the community have helped build trust with law enforcement.

“In my interactions with the community, I stress that it’s so important that they report crimes when they happen,” said Phu, who has been with the Oakland Police Department for more than seven years. “They are the eyes and ears for us — anything that they see might make a difference.”

A special police task force is in the works to focus more on hate crimes. Meanwhile, Chinatown residents and business owners say they are grateful for the volunteer citizen patrols.

Leung Fan Chiu, 72, said it is essential “to create a safe space and not be afraid to go out.”

“If there’s somebody doing good things for our community, that’s great,” Chiu, a restaurant entrepreneur, said through a Cantonese interpreter.

But Chiu said that he and his friends are not likely to use the service — perhaps out of a desire for independence.

Andy La, who runs the business Moment Invitations and Printing with his parents, wants protection with more teeth. He said the city should hire armed security guards, including bilingual ones.

“We are really grateful to see these citizen patrols around,” said La, 33. “Armed guards can be more visible. They send a visible message.”

As shoppers waited in line for sesame balls at Tao Yuen Pastry on a recent Sunday, four men from Asians With Attitudes scanned the crowd.

Imposing in their AWA shirts and masks, they were on the lookout for people who might need help walking to the car, the bus stop or getting home.

“We don’t want people to be scared. We just want them to be safe,” said team leader Jimmy Sing Hay, a truck driver from San Jose.

The group was multiethnic — Hay and Sakhone Lasaphangthong are Laotian, John Le is Vietnamese and Seng Saephan is Mien, an ethnic group from Southeast Asia.

Lasaphangthong urged anyone who wants to bully Asian people or yell racial slurs to find another outlet.

“No need to release your temper on innocent people,” he said. “Keep out of the community’s way.”

Lasaphangthong, a housing services director for an Oakland nonprofit, was incarcerated for two decades at San Quentin State Prison before being released in 2018.

Through the city’s Community Ambassadors Program, he roams the neighborhood, greeting store owners by name, respectfully bowing his head when he passes an older person, grabbing a broom to sweep sidewalks, waiting for shop owners to close for the day.

“This is my opportunity to really do my part,” he said. “Crime is happening and hate is spreading because people are traumatized. They’re losing their livelihoods. They don’t know what to do in a pandemic that has gotten worse.”

Both he and fellow volunteer Jennifer Li, an Oakland Chinese resident and administrative assistant who grew up in New York’s Chinatown, said they think “connecting to core groups” is the answer.

“I think we need more communication, not policing — but more talking to each other to figure out the situation,” he said.

“Sometimes, people turn to us to say, ‘I would love for somebody to stand with me until the bus arrives. I don’t want to be alone, just in case,’ ” Li said.

Hay said he hopes the Asians With Attitudes volunteers will be a deterrent to anyone thinking about harming a Chinatown resident.

“I’m here because the neighborhood must survive,” he said, “and because when I see the faces of the old women, I think of my grandmother who used to walk everywhere collecting cans.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.