Looking back at L.A.’s Chinatown to imagine a just future for Asian American communities

- Share via

Book Review

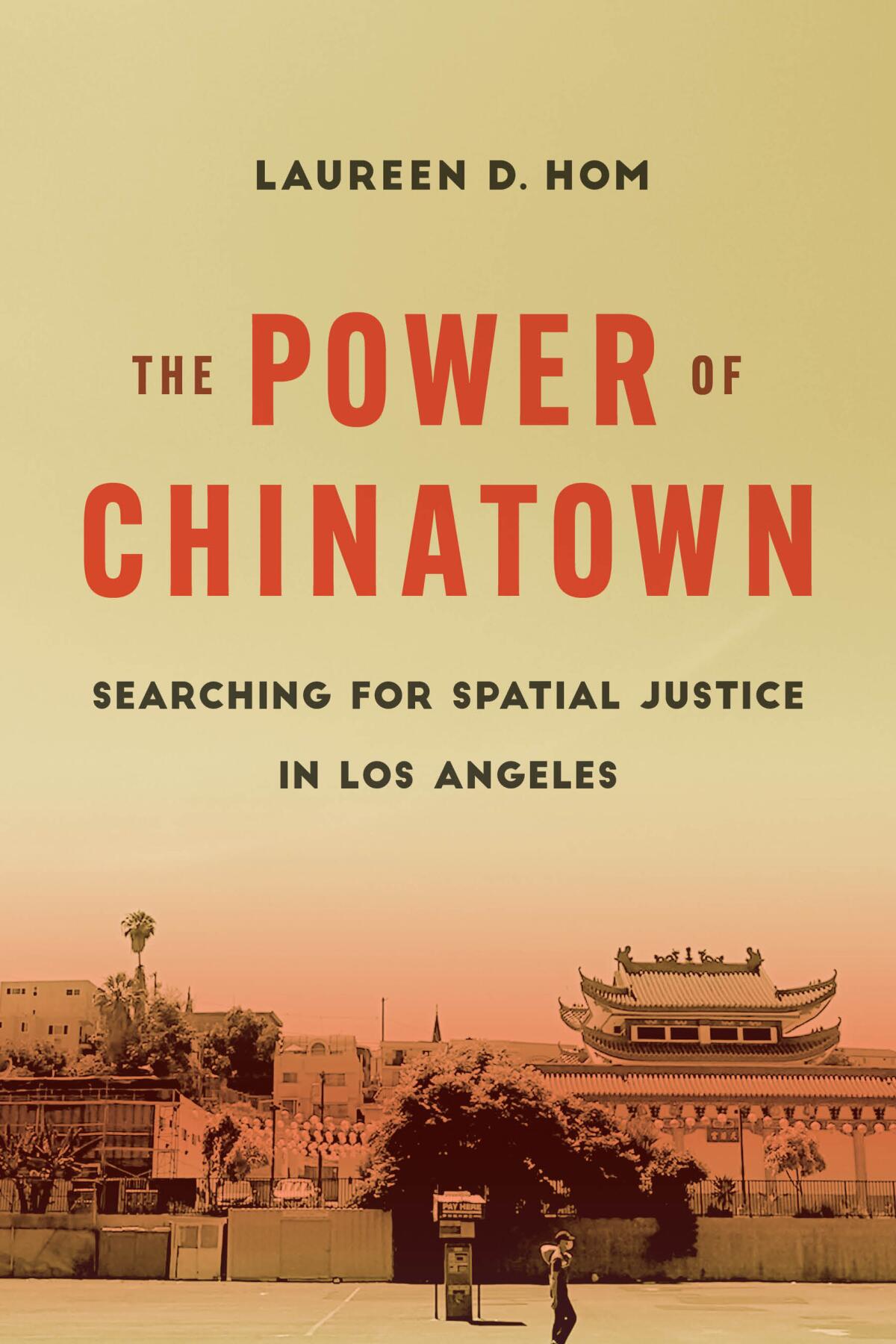

The Power of Chinatown: Searching for Spatial Justice in Los Angeles

By Laureen D. Hom

UC Press: $29.95, 300 pages

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Laureen D. Hom, the author of the new book “The Power of Chinatown: Searching for Spatial Justice in Los Angeles,” concedes that she had originally “dismissed Chinatown as too personal” and wanted to “move on,” like so many other Chinese Americans of her generation, when solidifying her dissertation plans as a PhD candidate in urban planning and public policy at UC Irvine. The deaths of both her grandmothers while she was in graduate school, however, forced Hom to reckon with what Chinatown meant for her family, now that these first-generation elders who’d lived there had passed on.

Hom took up Chinatown as an intellectual project, engaging in rigorous research and field work into the development history, political power and intimate human stories of the legacy neighborhood in Los Angeles. The result is a rich community history that illuminates the heterogeneity of Chinese (and more broadly, Asian) American racial politics in forging the evolving, continuously contested identity of an urban ethnic space — and a call to action for Asian Americans to imagine a just and equitable Chinatown for the next generation.

Hom’s research interests in gentrification and civic engagement in Asian American communities had led her in 2012 to Irvine, where Asian Americans had been settling in newer, often suburban areas rather than the historic urban ethnic spaces like San Francisco’s Chinatown, where Hom grew up.

That same year, however, Hom’s interest was piqued by the contentious development proposal for a Walmart Neighborhood Market in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. Residents, business owners and grassroots organizers all had starkly disparate ideas of whether a Walmart best served the community.

The Walmart opened in 2013 and closed three years later. Community leaders argued that it would bring resources to the predominantly low-income residents. Progressive activists, however, pointed to Walmart’s history of labor violations and its potential to drive out small businesses in Chinatown. The controversy also created questions about who has a say in controlling preservation and change. What role did members of the geographically dispersed Chinese American community in greater Los Angeles, such as Hom, play in shaping Chinatown’s future?

Hom wanted to know more: She embarked on an ethnography about the political culture in L.A.’s Chinatown as it pertains to gentrification, community development and cultural preservation. Hom’s fieldwork in 2014 to 2018 includes interviews with 52 community leaders. She also attended and participated in more than 90 community events and public meetings, and conducted meticulous archival research into the history of the neighborhood’s development.

Historic Chinatowns across the U.S. are facing the pressures of gentrification, contributing to the belief that these legacy neighborhoods are dying out and will soon disappear from the North American urban landscape. Hom argues against this narrative, asserting that ethnic enclaves are sites where “racial community identities are reproduced, challenged, and rearticulated,” and thus, the political processes that contribute and respond to gentrification are also a critical race project. The conflicts over gentrification in the community, Hom maintains, are a critical intersection of “how we define community, the commodification of land, and the impacts of the racialization of our communities.” Hom’s intervention as an urban theorist adds a powerful perspective to existing social and political case studies of L.A.’s Chinatown as a singular expression of race, class and culture.

In the late 1800s, Asian immigrants were perceived as unassimilable “others” and legally denied citizenship. Since the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act scrapped quotas favoring Europeans, the racialized identity of Asian Americans has largely become the image of the “model minority”: educated, upwardly mobile, white-adjacent.

Hom theorizes that certain elites in L.A.’s Chinatown have steered development to support this simplified representation of Chinese Americans, including those with business interests in the neighborhood who have manufactured a narrative of the community’s transition from an ethnic ghetto formed out of racial exclusion to a vibrant enclave with emerging socioeconomic power. Yet Hom also highlights progressive Asian American antigentrification organizers in L.A.’s Chinatown whose civic engagement grew out of the antiracist, anticapitalist and anti-imperialist philosophies of the 1960s.

Hom begins with a history of L.A.’s Chinatown through an urban planning lens, giving readers a racialized, political context for contemporary development issues. Hom traces the trajectory of the neighborhood’s development, informed by the intersection of immigration and urban development policies. Throughout the book, Hom shares interview excerpts from community members; it is a pleasure to “hear” directly from these voices, as Hom then expertly weaves together a number of dissenting narratives into a fascinating overview of a diverse community.

An acronym-heavy chapter studies the array of community organizations that have historically provided space for public participation in discussions over the neighborhood’s development. Hom’s survey gives readers a poignant view into the internal tensions that arise with place-based community work. Another chapter is devoted to how community leaders eschew the term “gentrification” for “balance” in Chinatown. Though there is, of course, dispute over the “correct” balance, such as maintaining affordable housing and luxury amenities in new residential developments, and creating new businesses that attract tourists without threatening legacy institutions that serve the community’s working-class residents. Later, she offers a multi-layered picture of how the neighborhood’s built environment — businesses such as galleries and restaurants, and public cultural events — all contribute to cultural displacement. This fascinating chapter interrogates the problem of defining ethnic culture amid a lack of policy tools to protect and preserve the neighborhood, while Hom returns once again to the question of who has the right to advance and control change in Chinatown.

“The Power of Chinatown” lucidly examines why historic urban Chinatowns still matter: Place-based racial politics are continuously reshaping the physical neighborhood environments, amid gentrification and forced displacement. Hom effectively argues that Chinatowns simultaneously persist and change; they are static sites with radical potential for equitable development, if the myriad Chinese and Asian American stakeholders across generations, socioeconomic status and immigration cohorts commit to a vision of spatial justice that foregrounds histories of resistance and collective power.

Jean Chen Ho is the author of “Fiona and Jane” and assistant professor of creative writing at Chapman University.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.