L.A. secondary school students face mostly online classes even when they return to campus

- Share via

The plan to reopen Los Angeles campuses relies heavily on providing students an in-person connection to friends and teachers, but the core learning for middle and high school students — and half of it for elementary school children — would still take place online, leading to mixed reviews among parents and advocates.

The approach to reopening in the nation’s second-largest school system is not only safety first, but safety well beyond what is required by state, county and federal guidelines. After months of negotiations with the teachers union, this approach — which requires full vaccine immunity for all school employees and a reduction in the community spread of the coronavirus — led to a tentative agreement between the union and Los Angeles Unified officials.

The district is targeting April 19 for reopening elementary school campuses, with middle and high schools to follow in late April or early May.

“It has taken time and painstaking effort to get an agreement that is right for the entire LAUSD community,” said Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, which represents teachers, nurses, counselors and librarians.

Union leaders pushed relentlessly for additional safeguards, which appear to surpass those across most of the nation, but align with many measures achieved by unions in large urban California districts.

Myart-Cruz spoke Wednesday at a joint news conference with L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner.

“This is the safest school environment — period, end of story,” Beutner said.

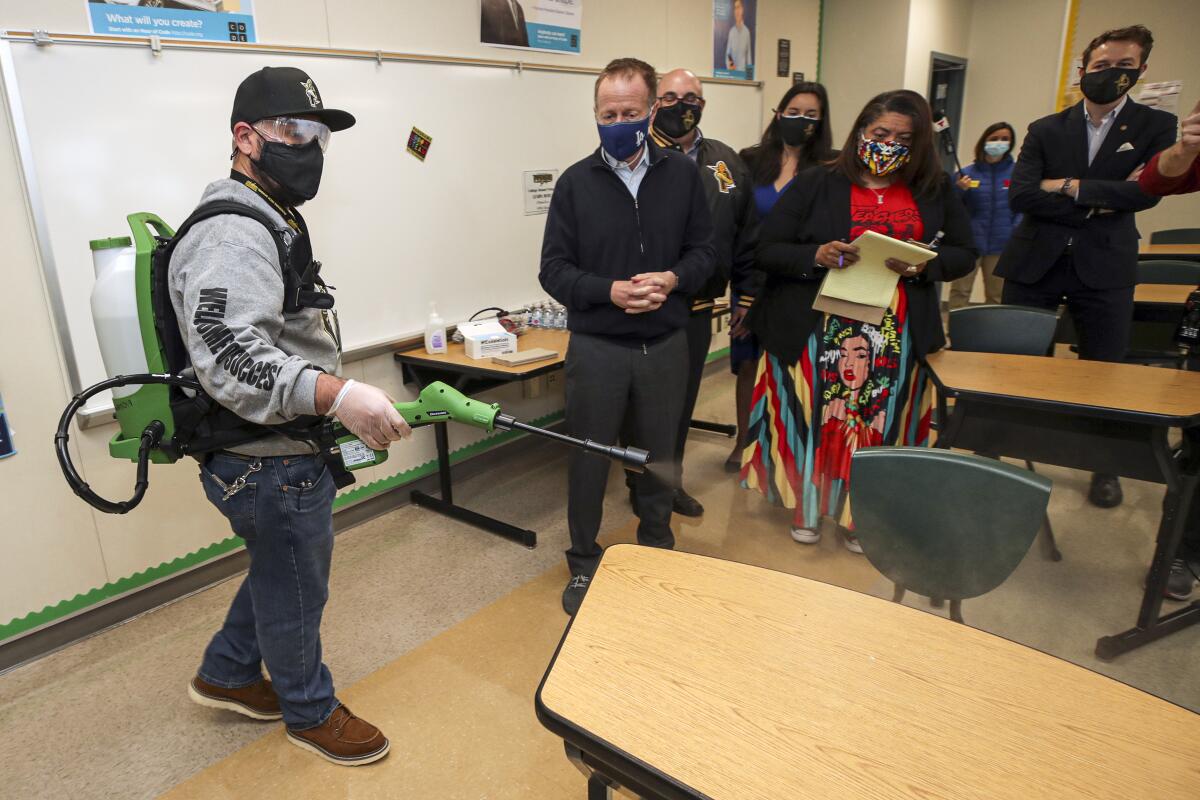

Beutner was referring to a suite of long-promised safety measures — regular coronavirus testing, district-provided masks, high-grade air filtering — that not only are fundamental to the agreement but also could address persisting concerns among parents and students wary of a return to campus. But he unveiled new elements crafted in the deal.

Perhaps the most striking provision is for middle and high schools to essentially trade Zoom-at-home for Zoom-in-a-classroom. Stable groups of about 12 students would spend two days a week on campus in an advisory or homeroom classroom working online with noise-cancelling headphones, while the teacher would be conducting classes over Zoom. Twelve people would be physically together but academically separated.

The group would unite briefly and remove headphones for an activity that would promote social and emotional learning or student well-being. They’d also be able to communicate, socially distanced, within their group during lunch — but not with students outside their groups. An exception would be students on a school sports team, which would operate under separate guidelines.

The advisory activity, Beutner said, would afford an opportunity for “someone to talk to about their life.”

“The idea is that this is the social emotional bond — that is the connection that students need with each other to be part of a school community,” he said. “We provide that opportunity for a safe and welcoming environment. Think of the middle school student who needs a warm place, a dry place.” What’s more, he added, “the internet works.”

A 12-person high school cohort is more strict than the county requirement. In guidelines distributed Tuesday, county officials recognized the difficulty of providing a safe yet robust academic and social environment at secondary schools, where students typically move from class to class. Health officials recommended creating stable groups of 60 to 80 students — and no more more than 100. Yet even these guidelines are optional.

Similarly, state and federal officials have insisted that campuses can be operated safely without vaccinations for teachers, which would allow campuses to reopen sooner. But unions in L.A. Unified and some other California districts would not back down from this extra level of protection.

L.A. Unified would offer a greater normalcy in elementary schools. Students could attend class for about three hours Monday through Friday in either an a.m. or p.m. shift. The split day would allow space for groups to be socially distanced and limitthe potential spread of infection.

A huge boost for working parents would be campus-based supervision for the other half of the school day. Still, the end result would be a live instructional day that is 50% of a normal school day, underscoring the need for academic recovery efforts.

“Many elementary school parents are breathing a huge sigh of relief today,” said Katie Braude, chief executive of Speak Up, a local advocacy group. “For months, our parents have been advocating for the option to have students return to campus safely. Many of our students, especially those with disabilities and very young kids, have truly suffered during school closures and missed out on much of their education for an entire year.”

Older students, she added, also need to work with their teachers in person again.

It’s not clear how soon students with disabilities will have access to the special additional support they would need to return. The agreement indicates that negotiations will continue in this area.

Some parents and students said the deal is not enough to bring them back.

“My middle schooler will not be going back if she is only going to sit in her advisory all day on Zoom,” said Pamela S. Brown, who has a daughter in eighth grade at the Girls Academic Leadership Academy in Mid-Wilshire. “I don’t see the benefit for her. It sounds like it will be distracting for students, and I can’t understand how the teachers will teach their courses with advisory students working in the room with them.”

But she’s ready to send her second-grader back to Community Magnet Charter School in Bel-Air: “He really suffers emotionally not being in school. The devil’s in the details, though, and I’m not confident they can pull this off. My son takes a bus.... Do they have enough buses to transport them safely?”

Beutner had some information on this point, saying that bus monitors would be hired to enforce social distancing.

Distance learning has been an ordeal for Joy Smith, a single parent and a nurse. Her kindergarten son and third-grade daughter attend Coliseum Street Elementary in the Crenshaw area.

Smith’s mother tried to help with supervision, but she has eye problems and doesn’t understand computers. With her children struggling, she started paying $98 for an in-person tutor on Tuesdays and $240 a week for her children to attend a day-care learning pod, where the main assistance is helping students stay online.

She said the teachers union demands have prevented a quicker return to campus: “The students are falling behind. Something is wrong.”

In contrast, parent Jazmin Garcia said the union is looking out for parents. Still, she’s hesitant to return her second-grade daughter to City Terrace Elementary in East L.A.

“I haven’t been vaccinated and a grandparent who has daily contact has not been vaccinated,” she said. “Now that there’s an agreement, as parents, we still have to make sure when they do reopen that the cleaning does happen on a daily basis.”

The emphasis on safety — by the district and the union — could prove key to bringing some students back. Families will be given the option to remain in distance learning for the remainder of the academic year.

Jessica Garcia, a junior at Lincoln High School on the Eastside, along with two siblings and her father, contracted COVID-19 in November. The 17-year-old is reluctant to return, even though online classes have been difficult.

“I don’t think I’ll be going back,” she said during a break from online classes Wednesday. “Going out and putting that risk on my family, it would just be a lot to handle. I don’t think I would risk getting my family sick.”

She worried that high school students might not abide by safety rules. Her friends, she added, are about evenly split on returning.

But for Jude Choi, a senior at Marshall High School in Los Feliz, two days a week on campus “is better than nothing.”

“When I’m at home there’s distractions everywhere — my phone, my computer, what have you,” he said.

He believes his parents would support him returning to campus, even though his mom recently had surgery that could make her susceptible to COVID-19. He’s also wary of taking public transportation from his home in Lafayette Park, as he sometimes did in the past.

He misses his friends — even the building.

“I really like our campus, it’s beautiful,” he said. “Just being able to go would be a treat.”

Times staff writers Nina Agrawal, Melissa Gomez and Teresa Watanabe contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.