Parents struggle with a new dilemma: Is it safe to send kids back to school?

- Share via

Katy Meza knows full well the pain distance learning is causing her son Matthew. The third-grader struggles with isolation, gets frustrated sitting in front of the computer for hours and is stalling academically.

Still, Meza says she’s not prepared for him to return any time soon to in-person schooling at Bryson Elementary School in South Gate.

Almost every family she knows has someone who has fallen ill with COVID-19. Her neighbor died of the disease, and his wife was hospitalized. And Meza has no confidence that her son’s school — which before the pandemic often lacked toilet paper and soap — can keep him safe or prevent him from becoming infected with the virus and bringing it home to his grandparents.

“I can try and teach him his multiplication tables or fractions,” she said. “But we can’t get back our health or our lives.”

On Tuesday, an agreement reached between L.A. Unified and the teachers union that aims to bring students back to campus by mid-April set in motion a critical decision among L.A. parents: Should they send their children back? It’s a question being faced by parents across the county as policymakers push for schools to begin reopening throughout California and have earmarked $2 billion in education funds for elementary schools that offer in-person learning next month.

The agreement, which must be ratified by union members, would set up a combination of in-person and online learning.

There is a wide disparity of opinion among parents and caregivers on the issue.

Some parents, frustrated with the mental-health and academic effects of remote learning, are eager to see their children return to classrooms and are demanding a swift resumption of in-person learning.

“Schools can safely be reopened now, full time, five days a week, of course with proper mitigation,” said Megan Bacigalupi, a parent advocate with the newly formed group Open Schools California. “Our group will keep fighting until all kids are back in school.”

Others are wary — especially in places that have felt the devastating and inequitable effects of COVID-19. Even if their school reopens, they are keeping their children home with continued distance learning, an option that school districts must offer during the pandemic.

Even as the daily toll of COVID-19 deaths declines, Latino residents of Los Angeles County are still dying at three times the rate of white residents.

“There’s a lot of pain in the community,” said Maria Brenes, executive director of the Eastside advocacy group InnerCity Struggle. “There’s going to have to be a lot of engagement for families to feel like, ‘OK, the conditions are there where I feel my child will be safe.’”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said it is possible to reopen school campuses safely with proper safeguards — including universal mask wearing, social distancing, frequent hand-washing, enhanced cleaning and ventilation of schools, and other protocols.

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Last month, L.A. County met the state threshold for reopening elementary-school campuses, leading many to open their doors or make plans to do so soon. Middle and high schools will probably be permitted to reopen within days. Districts in wealthier communities have led the charge for swift school reopenings.

Both national and local district-level surveys highlight split parent stances on returning, with families weighing many factors including the impact COVID-19 has had on their local community, whether they live in intergenerational families and whether they trust that their school can keep their children safe.

A Times survey of over 20 school districts found that those in wealthier, whiter communities were more likely to be moving full steam ahead to reopen elementary schools.

Mandy Zhou of San Marino said she hesitated when her son’s first-grade classroom reopened for in-person learning late last month. She said most of her friends decided to keep their children home in this affluent district, where the majority of students are of Asian descent.

Zhou said her decision to allow her son to return was influenced by San Marino Unified School District’s frequent communication with parents soliciting their input, she said. She knew that her son was growing bored with distance learning and felt he needed more direct interaction with his teacher and peers.

The day he was set to return to campus, Zhou said, her son woke up and put his backpack on at 9 a.m., even though school didn’t start until almost noon. When she drops him off, she sees him find socially distanced ways to play with classmates.

“Even though they’re six feet apart, they’re still playing. They’re playing rock paper scissors, they’re running around,” she said. “He’s pretty happy.”

A recent survey of families of elementary-school students in the Arcadia Unified School District found that about half wanted to continue with distance learning while the other half wanted to return to campus, said spokesman Ryan Foran. The district, where nearly two-thirds of students are Asian or Asian American and about a quarter come from low-income families, is planning to reopen for elementary-school students in April.

Times survey finds profound disparities in distance learning between children attending schools in high-poverty areas and those in more affluent ones.

Long Beach Unified, which is planning to open its doors for in-person schooling for students in transitional kindergarten through fifth grade at the end of March, found a similar split. About 50% of parents of elementary-school students have opted for online learning while 44% chose in-person instruction. Five percent did not make a selection, said spokesman Chris Eftychiou. A majority of the district’s students are Latino, and about 65% are from low-income families.

At Beverly Hills Unified, meanwhile, more than two-thirds of students were set to return to in-person learning when elementary-school campuses reopened Monday while 32% would remain online, said spokeswoman Rebecca Starkins. About 70% of the district’s students are white, and about 17% are from low-income families.

But at Inglewood Unified, where a majority of students are Latino and about 40% are Black, around 71% of families in a survey earlier this year said they did not feel comfortable sending their children back to school once they were allowed to return, officials said.

Los Angeles Unified, which surveyed parents in November, reported that about 66% of families said they preferred to continue with online learning when students were able to physically return to campus. About 38% of Black families, 30% of Latino families and 29% of Asian families preferred in-person learning, compared with 58% of white families.

LAUSD Supt. Austin Beutner has said that in the coming weeks parents will be asked to consider their choice again.

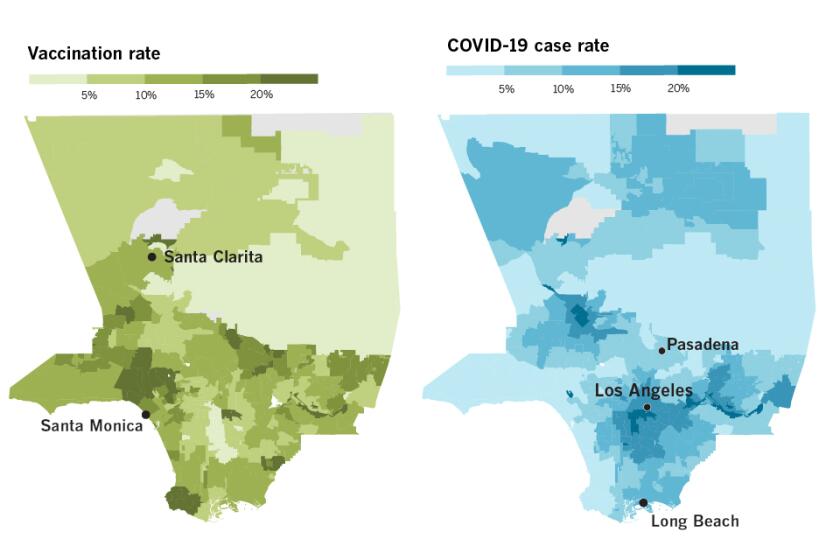

Disparities are revealed in detailed data tracking the progress of the COVID-19 vaccination effort in more than 340 neighborhoods across L.A. County.

On a national level, the Pew Research Center in February found that public opinion on school reopenings varied based on race and income: Black, Latino and Asian adults were more likely than white adults to say that the risk that teachers and students would become infected or spread the coronavirus should get a lot of consideration in school reopening decisions. Large majorities of Black, Latino and Asian adults also said schools should wait to reopen until teachers had been vaccinated, compared with about half of white adults.

Researchers at USC similarly found that the question of whether to reopen was divided along racial and economic lines. In a national survey, 63% of white parents favored some form of return to in-person learning as did 68% of those with incomes over $150,000. More than half of Black, Latino and Asian parents, meanwhile, favored remote learning.

Parents on both sides of the issue said they felt left out of decision making, and many said their school districts needed to do a better job of communicating with and engaging parents.

“I’d like L.A. Unified to take us into account,” said Meza of South Gate. “These are our children. And they need to work with us to come up with a plan so that we can feel safe.”

Lydia Friend, who lives in Watts and has been an activist in the community for decades, said she was eager for her grandchildren to return to school. She worries about the toll on the mental health of children being isolated, she said.

“Our children are suffering at home,” she said. “Especially for the parents that can’t afford day care, for the parents that are working and kids stay home.”

Friend said she was constantly talking with families in the community and that many of them were reluctant to allow their children back on campus, but she believes it’s important for them to have the option of returning.

What makes her most frustrated, she said, is feeling as if parents and caregivers have not had a voice in decisions.

Brenes, who has two children in Eastside schools, said school leaders needed to work extra diligently to communicate with families if they wanted them to feel secure about their children’s safety.

“Our community has been firsthand witness to how harsh the pandemic has been,” she said, “and how they don’t always feel like they’re prioritized or protected.”

That sense has been reinforced over and over again throughout the pandemic, as Black and Latino students were disproportionately left behind during school closures by lack of access to technology. Black and Latino communities have been disproportionately harmed by the virus and vaccines have disproportionately gone to white and wealthy communities, Brenes said.

All of it leads people to question: “Does the system really have our best interests in mind?” Brenes said. “You can’t separate that from the question of reopening.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.