Golden State Killer pleads guilty to murders and other crimes that terrorized California

- Share via

They stood in the makeshift courtroom to confront the man who had bound and brutalized them decades ago.

The masked assailant who had terrorized California as the Golden State Killer in the 1970s and ’80s sat hunched before them — now a thin, stooped, 74-year-old man.

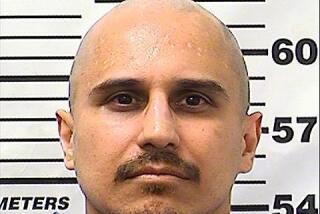

Wearing orange jail clothing and a clear protective face shield, Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. admitted guilt Monday to more than a dozen murders and scores of home invasion rapes and other crimes at a court hearing in a Cal State Sacramento ballroom.

As prosecutors read aloud the gruesome details of each crime, victims and their relatives stood in the audience.

Some looked DeAngelo in the eye. Others couldn’t bear to. But all wanted him to know: They were there. And they were not afraid.

“We don’t have anything to be ashamed of, so we can stand up, and he can take a look at us,” said Kris Pedretti, one of the earliest victims, who was 15 when she was raped in 1976. “We’re not afraid of him. I think that’s more powerful than us staying seated and being a Jane Doe. Because, if he looks out, he doesn’t know who is who. He will today.”

In a hoarse voice, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 murders and 13 charges of kidnapping for purposes of robbery — the only crimes with which he is charged. He also admitted to some 62 other crimes of rape and abduction for which the statutes of limitations long ago expired.

Prosecutors agreed not to seek the death penalty — the main request made by DeAngelo’s public defenders. In return for his guilty plea, DeAngelo will be sentenced to prison for the rest of his life.

DeAngelo’s crimes ran from at least 1973 to 1986 and involved attacks on some 106 children, men and women in 11 counties, ranging from Sacramento to Orange. Some 50 women and girls were raped.

Frustrated detectives and the public dubbed the unknown assailant variously as the Visalia Ransacker, the East Area Rapist, the Diamond Knot Killer and the Original Night Stalker.

Detectives did not have a final named suspect until 2018, when they used crime-scene DNA and genealogy services to identify the killer’s cousin and then, finally, DeAngelo, a former police officer.

Sacramento County Assistant Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. Thien Ho called the crimes “simply staggering” in scope.

“His monikers reflect the sweeping geographical impact of his crime,” Ho said during Monday’s hearing. “Each time, he escaped — slipping away silently into the night, leaving communities terrified for years.”

Ho said that DeAngelo, sitting in a Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department interview room hours after his arrest, spoke to himself, saying, “I did all those things. I’ve destroyed all their lives. So now, I’ve got to pay the price.”

Monday’s hours-long plea hearing was scripted, allowing no room for ad-libbed confessions.

Prosecutors recounted in horrifying detail how DeAngelo would tie up his victims with shoelaces; when assaulting couples, he would place dishes on their backs, saying he would kill them both if he heard dishes fall. They quoted the explicit threats and sexual demands he growled into their ears and described how he would help himself to food or beer from his victims’ kitchens before and after raping them.

DeAngelo scarcely spoke during the hearing, answering questions from Superior Court Judge Michael G. Bowman in a low “yes” or “no” and responding to the charges against him with “guilty” or “I admit.”

The judge, defendant and lawyers faced an audience of nearly 200 and banks of television cameras. Large projection screens displayed the faces of those at the podium, and the hearing was livestreamed by Sacramento County Superior Court, a national true-crime entertainment network and multiple news programs.

To an early love interest, Joe DeAngelo was energetic and worldly. Now, nearly 50 years later, he stands accused of an extended spasm of violence — home invasions, rapes, murders — in the 1970s and ’80s.

Victims have been told to prepare impact statements to be read aloud during proceedings scheduled to begin Aug. 17 and to last a week before DeAngelo’s sentence is declared.

Though they weren’t able to address the court directly Monday, the victims found a way to make their presence felt.

As details about the murders of Greg Sanchez and Cheri Domingo were read aloud, Cheri’s daughter Debbie Domingo stood to face DeAngelo.

Jennifer Carole also stood, hands gripped behind her back, as the 1980 bedroom killings of her father and stepmother, Lyman and Charlene Smith, were described. She took off her mask so she could be seen but did not make eye contact with DeAngelo. Afterward, retired Sacramento County Sheriff’s Detective Carol Daly stepped up to give Carole a hug.

DeAngelo’s whispery voice and use of a wheelchair did not evoke sympathy from Carole.

“Rest assured, it’s still an act,” she said, echoing the opening statement by prosecutors who said DeAngelo briefly feigned insanity when arrested for shoplifting in 1979 and appeared to do so again hours after his 2018 arrest, when he blamed the crimes on someone called “Jerry.”

“I didn’t have the strength to put him out. He went with me,” Ho said DeAngelo uttered while in the police interview room. “I pushed Jerry out and had a happy life.”

Sacramento County Dist. Atty. Anne Marie Schubert said DeAngelo was competent to stand trial, and his use of a wheelchair Monday suggested he was malingering.

His lawyers said the wheelchair was used at the request of court security to help move DeAngelo in and out of the room.

Six family members of Janelle Cruz, DeAngelo’s last known victim, stood together to confront him as he pleaded guilty to murder and admitted to raping the 18-year-old.

Cruz was bludgeoned to death in 1986 with what detectives believe was a pipe wrench that had been stolen from the family’s backyard days earlier.

DeAngelo appeared to look down, not returning their gaze.

He again looked down as four relatives of Brian and Katie Maggiore, chased down and shot while taking an evening stroll in Rancho Cordova, stood just feet away from the raised stage where DeAngelo and his lawyers sat.

All the women who were raped were referred to as “Jane Doe,” a decision that was criticized before the hearing by some who sought to be shed of decades of social stigma over their attacks.

“I don’t want that,” Pedretti said. “I want to be seen as a real person that he did this to and not as some Jane Doe.”

The Sacramento County district attorney’s office told Pedretti the decision had been made for her, she said, but conceded her request to be allowed to stand during the hearing when her 1976 attack was mentioned.

While details about how DeAngelo had raped her were being read, Jane Carson-Sandler walked up to the edge of the stage to face DeAngelo squarely. He did not look at her.

Other victims silently cried, dabbing their eyes with tissue.

As Monday’s hearing wrapped up, the daughter of one rape victim walked out singing, “Bye-bye, Joe, bye-bye ...”

Because of COVID-19 spacing requirements, the proceeding was moved to the ballroom at Cal State Sacramento, the school from which DeAngelo received a criminal justice degree in 1972. The audience was composed almost entirely of victims and their families, with spaces awarded by lottery for 27 members of the media.

There was one notable empty chair — for Phyllis Henneman, the first-recognized victim of the East Area Rapist. Henneman, who has been battling cancer for the past year, was admitted to the hospital over the weekend.

Nearly 40 victims and family members rose and stood silently to face DeAngelo when it came time to read the charges for the 1976 rape of Henneman.

From beginning to end, the crimes involving DeAngelo played out in the public eye.

The East Area Rapist drew so much media attention that he caused a public panic, prompting citizen patrols, bounties and a run on sales of guns, door locks and guard dogs. Midway through the series of rapes, detectives believe, the attacker began to feed off that public hysteria, and he began to instruct victims to pass on death threats to the police and future victims.

DeAngelo was fired from his Auburn, Calif., police job in 1979 after he was caught shoplifting. The murders that ensued as he and his wife moved to Southern California — again involving bedroom attacks and rapes — at first went unconnected. The unknown assailant was given new local nicknames: the Diamond Knot Killer and the Night Stalker, later changed to the Original Night Stalker after another serial killer took that sobriquet.

Advances in forensic DNA changed the case dramatically. In 2001, detectives were able to link the attacks up and down the state.

The crime spree became media fodder again as a television series, then was picked up by a Los Angeles writer, Michelle McNamara, who re-branded the perpetrator as the Golden State Killer and marketed a book on her attempts to chronicle, and perhaps solve, the case.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.