Murder or self-defense? Ex-school officer on trial for shooting girl in moving car

- Share via

When the car sped past him in a Long Beach parking lot, former school safety officer Eddie Gonzalez was either a dedicated public servant in fear he would be run over by a fleeing suspect — or a killer who made a wild and reckless decision to shoot into the back of a car full of youths who disobeyed him.

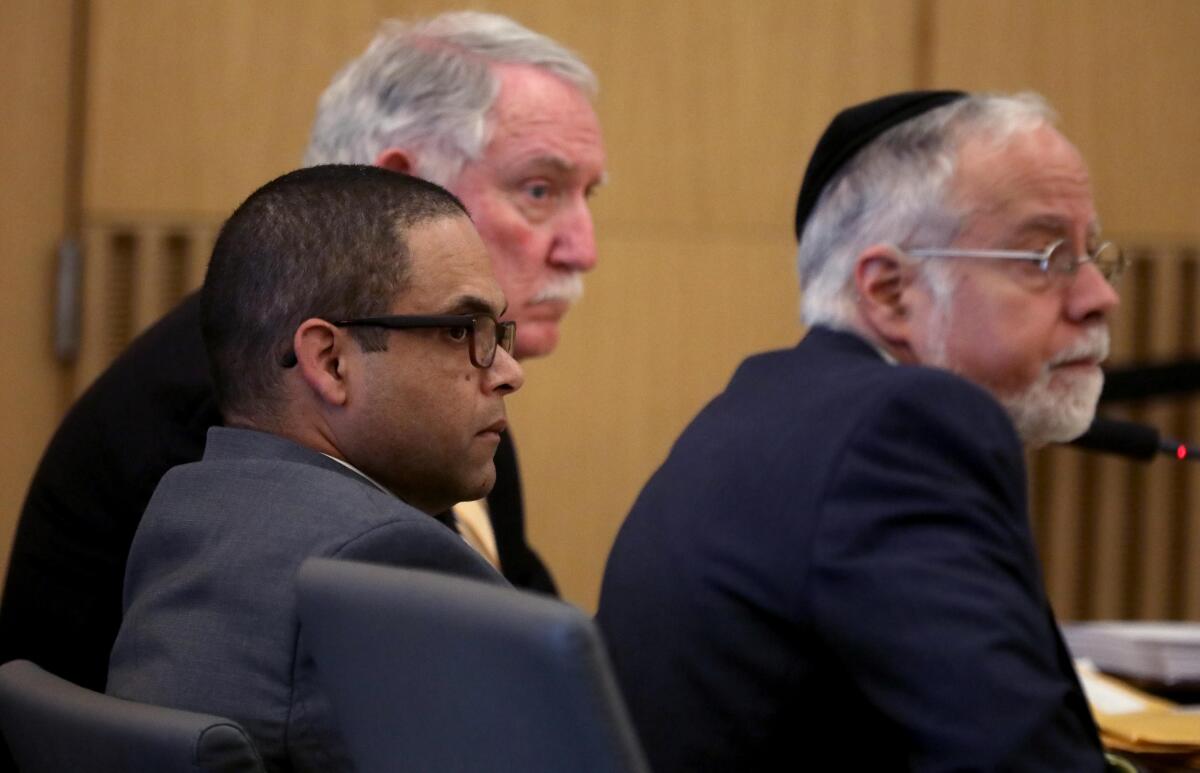

Those were the lines prosecutors and a defense attorney drew Thursday afternoon as opening arguments began in the guard’s murder trial in the September 2021 killing of 18-year-old Manuela “Mona” Rodriguez, who was shot dead near Millikan High School when Gonzalez fired two bullets into a vehicle she was riding in.

The shooting sparked outrage and protests. School officials quickly moved to fire Gonzalez, 54, and then-Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia called for him to be prosecuted. Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón obliged, filing murder charges a month later.

“The only reason he fired his gun, the only reason Mona lost her life, was because three people disobeyed him,” L.A. County Deputy Dist. Atty. Kristopher Gay said Thursday, emphasizing that Gonzalez was in “no danger” when he opened fire that day.

Gonzalez was responding to a report of a fight between Rodriguez and a 15-year-old girl on Palo Verde Avenue near Millikan High School. Rodriguez was traveling with her boyfriend, Rafael Chowdhury, and his teenage brother when they spotted the other girl, who’d recently gotten into a fight with one of Rodriguez’s friends.

Chowdhury previously told police that he and Rodriguez were looking to buy shoes for their 5-month-old daughter and happened upon the girl on the day of the brawl. At Gonzalez’s 2022 preliminary hearing, however, a police officer testified that the group had gone out searching to assault her.

“This wasn’t a fight,” defense attorney Michael Schwartz said Thursday, painting Rodriguez as a dangerous felony suspect whom Gonzalez had to stop. “This was a planned beat-down.”

Gonzalez threatened to pepper-spray both girls if they didn’t stop fighting. Rodriguez and her group went back to their car, but not before she made a threat against the 15-year-old’s family, according to preliminary hearing testimony. Gonzalez followed and ordered her to stop.

As the car drove off, Gonzalez shouted and opened fire. Rodriguez, who was in the vehicle’s passenger seat, was struck in the head, police said. Chowdhury and his brother were not hit. Gonzalez previously told Long Beach police investigators he was aiming at the driver but missed and struck Rodriguez.

Rodriguez suffered severe brain damage and was taken off life support a week later. Last year, the Long Beach Unified School District settled a wrongful death suit filed by her family for $13 million.

Gonzalez has claimed he acted in self-defense because the car could have struck him. But Gay argued Thursday that “the defendant responded to youthful disobedience with deadly force.”

As his first witness took the stand late Thursday, Gay displayed cellphone video that captured the shooting. A woman’s screams could be heard as the video displayed Gonzalez letting off his two-shot burst. Several of Rodriguez’s relatives could be seen turning away in the gallery, and one woman teared up.

Schwartz told jurors that although Rodriguez’s death may have been a tragedy, it was “not a crime.”

The veteran defense attorney — who has made a career of defending police officers from prosecution in excessive force cases — noted the car’s tires were turned toward his client.

“He was right by that car as it peeled into his path,” Schwartz said.

Many large police departments, including the LAPD, no longer allow officers to shoot at moving vehicles unless the occupants pose a threat beyond the vehicle itself.

Whereas Gay described the fight between the girls as a schoolyard dust-up, Schwartz painted it as a planned attack. When Gonzalez opened fire, his attorney said, he was trying to stop dangerous felony suspects who had participated in a premeditated assault.

Schwartz said he plans to call three witnesses who will testify that Gonzalez was in the path of the vehicle when he shot. Gay’s first witness, a high school student who filmed the shooting, said Gonzalez fired his second shot while he was behind the car.

The trial is expected to last roughly one week.

In a series of letters sent to the court asking for a reduction of Gonzalez’s bail at an earlier phase of the trial, his relatives described him as a dedicated, hardworking family man who worked as a cable repairman for decades before pursuing his dream to be a law enforcement officer.

“On Sept. 27, 2021 — my Dad went to work, as he has done for decades, to provide for his family,” wrote his daughter, Jasmine. “He is not a malicious or vengeful person and I hope that through this trial you and a jury of his peers can see that is the obvious case.”

Gonzalez was a reserve Orange County sheriff’s deputy from 2015 to 2018, according to the letters, and relatives claimed he was once named “reserve deputy of the year.” A spokeswoman for the Sheriff’s Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Gonzalez’s law enforcement career had taken a downward turn in the years before the shooting as he bounced between jobs. He worked for the Los Alamitos Police Department from January to April 2019, according to city officials who declined to provide details about his departure.

A few months later, he joined the Sierra Madre Police Department in September 2019, but again left after less than a year on the job, according to a police spokeswoman, who said the city “chose to separate from Officer Gonzalez” but would not elaborate.

Police officer disciplinary records are largely shielded from public view under California law, unless the officer has used deadly force or been accused of sexual misconduct or dishonesty on duty.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.